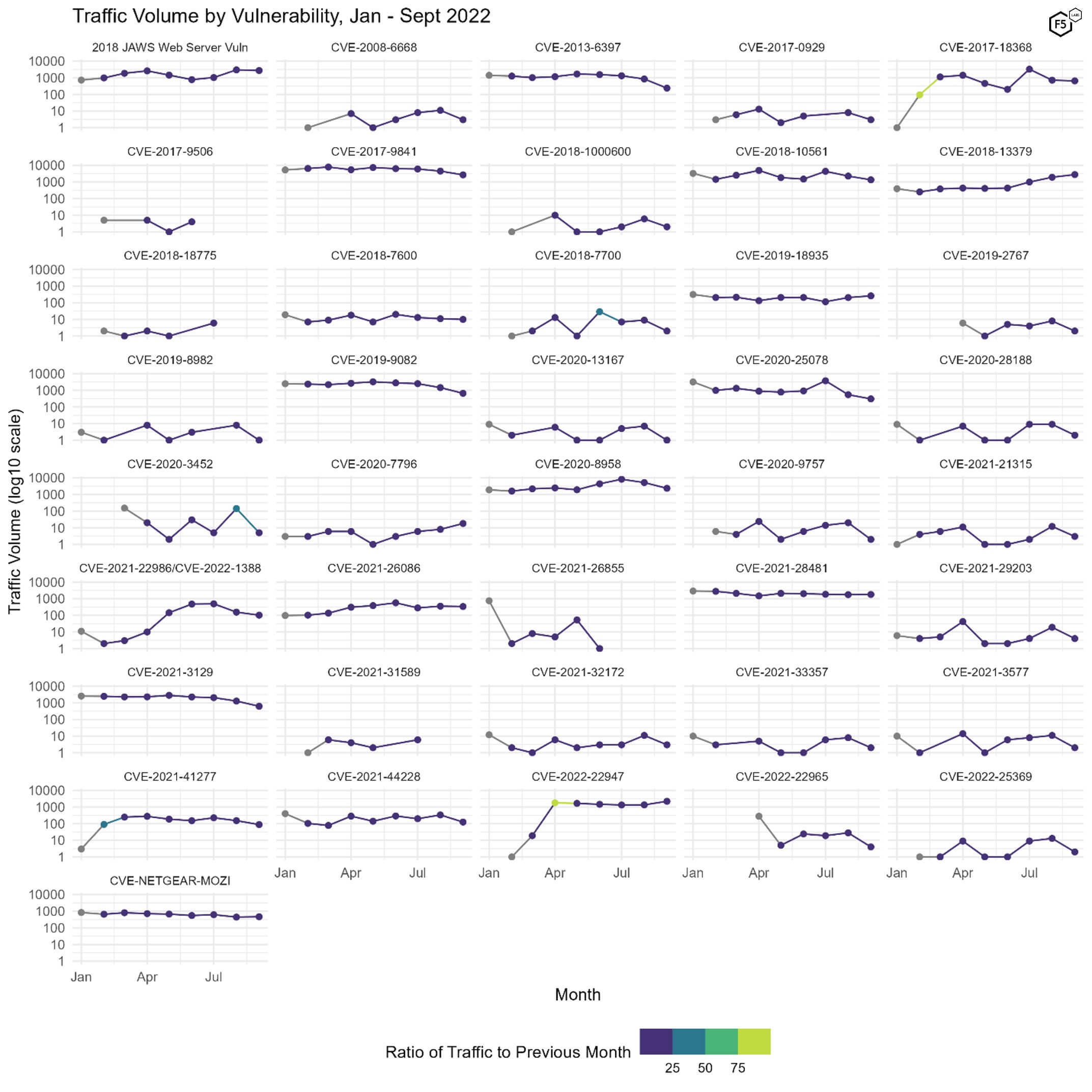

Figure 3 shows one of our more successful attempts to visualize the traffic in a way that makes it possible to identify moments when a vulnerability hit the big time. The coloration of the curves represents the ratio of a CVE’s traffic in a given month to the previous month. Vulnerabilities that spike in traffic volume are shaded towards green and yellow and vulnerabilities that are static or diminish are shaded in purple.

Figure 3. Plot of all 41 tracked CVEs over time. Color indicates the ratio of change from the previous month. Note log10 scale on the y axes.

There are a few dramatic points of growth in Figure 3: CVE-2017-18368 in February, CVE-2020-22947 in April, and the smaller but still noticeable surge in attention in CVE-2021-22986 and CVE-2022-1388.1 Unfortunately we can’t account for the reasons behind these periods of growth, but at least it is clear which vulnerabilities defenders should be prioritizing.

Port Data

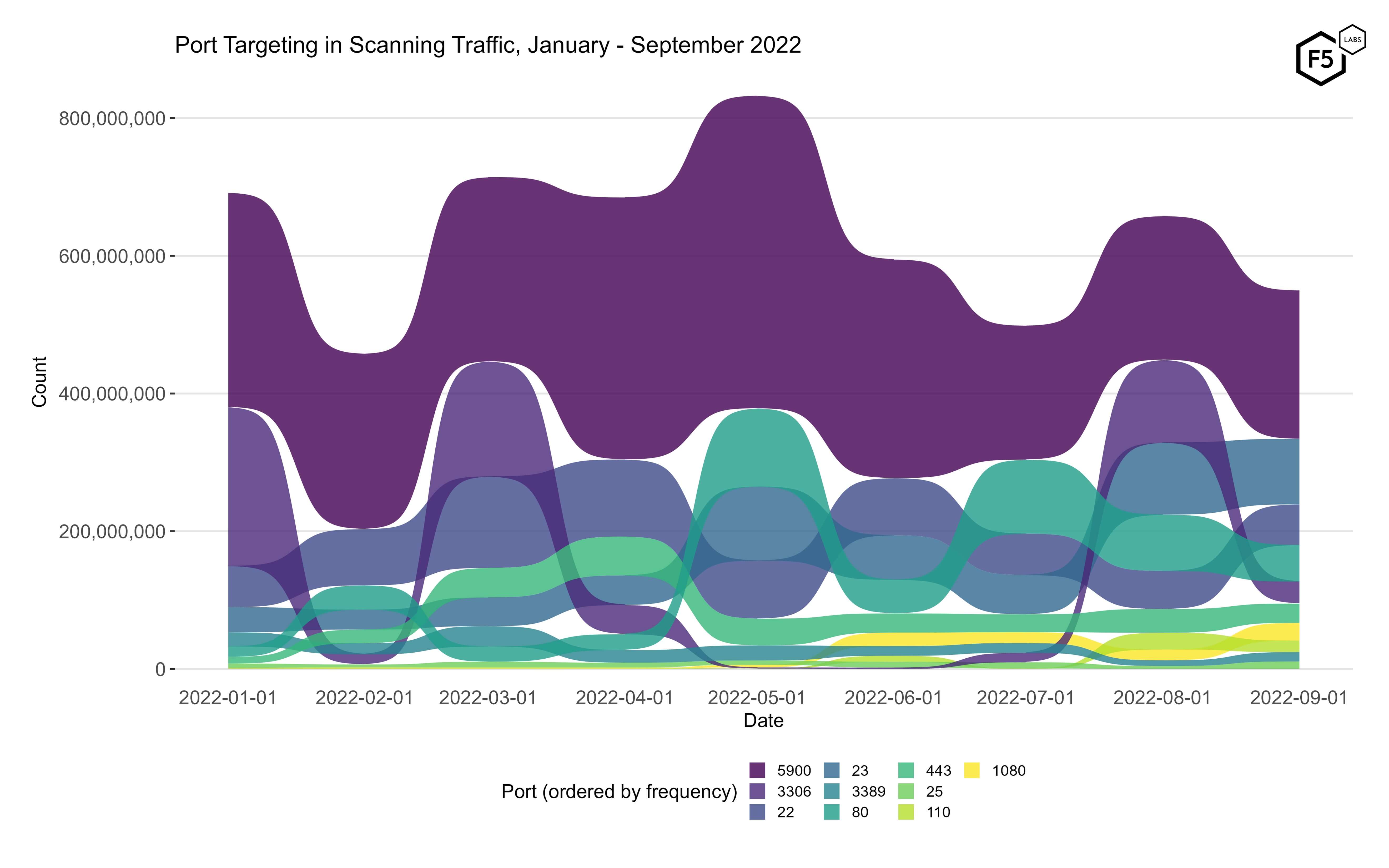

Most of our inquiry is focused on web traffic, but to get a sense of how traffic targeting ports 80 and 443 compares with other ports, Figure 4 shows the traffic volume and ranking for the top ten targeted ports from January to September of this year. Port 5900, which is usually used for Virtual Network Computing, has consistently been targeted more than any other port, but behind that in September were ports 23 (telnet) and 22 (SSH). As we've noted before, the top targeted ports tend to be those used mainly for remote access, followed by database and mail related ports.

Figure 4. Port targeting in scanning traffic, January - September 2022. While traffic targeting port 5900 (Virtual Network Computing) has been the top port for the entire period, other ports have traded positions and prominence continuously throughout the year.

Table 2 shows the volume of traffic targeting the top 10 ports in September. The best news here is the disappearance of port 445 (SMB) from the top 10, although it was still ranked 13th with 0.29% of total traffic.

| Port | % of total Connections | Typical Application |

| 5900 | 34.37% | VNC |

| 23 | 15.17% | Telnet |

| 22 | 9.39% | SSH |

| 80 | 8.50% | HTTP |

| 3306 | 5.11% | Mysql/MariaDB |

| 443 | 4.45% | HTTPS/TLS |

| 1080 | 4.11% | SOCKS Proxy |

| 110 | 2.70% | POP3 |

| 3389 | 2.16% | RDP |

| 25 | 1.74% | SMTP |

Table 2. Traffic volume for top 10 ports in September.

Conclusions

The main conclusion for this month is the same as for every month: we should all patch vulnerabilities as aggressively as possible within the overall risk appetite of our organizations. Seeing a vulnerability (or ports) in our data that applies to your organization should be taken as a signal that attackers have recently stepped up their attention to that vector.

Other than this, it is interesting to see a credential disclosure vulnerability in security infrastructure at the top of the list after months of focus on vulnerabilities of two categories: RCEs and IoT vulnerabilities. 30 months on from the beginning of the pandemic and the onset of the Great Remote Work Experiment, it can be easy to forget what a transformation in attack surface has occurred in the last few years. Because of this, the emergence of CVE-2018-13379 shouldn’t just provoke a review of owners of the Fortinet SSL VPNs, but should provoke a review by everyone into their VPNs and other remote access services.

Recommendations

Technical/Preventative:

- Scan your environment for vulnerabilities aggressively.

- Patch high-priority vulnerabilities (defined however suits you) as soon as feasible.

- Engage a DDoS mitigation service to prevent the impact of DDoS on your organization.

Technical/Detective:

- Use a WAF or similar tool to detect and stop web exploits.

- Monitor anomalous outbound traffic to detect devices in your environment that are participating in DDoS attacks.

Today we are going to look at the latest threat intelligence covering the month of September from our data partners Efflux. As we discussed in the first sensor intel series piece, these monthly updates are focused on traffic targeting known CVEs. While the volume of traffic targeting known CVEs is a small portion of the entire data set, much of the traffic that the sensors log is noisy or equivocal in significance, whereas the CVEs are relatively easy to identify and therefore constitute higher-quality intelligence.

After seeing many of the same CVEs occupy the bulk of attacker attention over the last several months, September saw a comparative newcomer at the top, in the form of CVE-2018-13379. This is a directory traversal vulnerability in certain versions of the Fortinet FortiOS and FortiProxy SSL VPNs.2 We should also note that in September 2021, Fortinet disclosed that a malicious actor had published 87,000 sets of Fortigate SSL VPN credentials based on this exploit, and recommended that even customers who had upgraded to a mitigated software version should reset passwords and hunt for indicators of compromise.

The Fortinet vulnerability just narrowly beat out the JAWS web server/DVR vulnerability we discussed in the August sensor intel update, which has no CVE number assigned.3

September Vulnerabilities By the Numbers

Figure 1 shows the volume of traffic targeting the top 10 CVEs for the month of September.

Table 1 shows traffic counts for all of the vulnerabilities tracked in September, along with the change from the previous month.

| CVE Number | Count | Change |

| CVE-2018-13379 | 2772 | 858 |

| 2018 JAWS Web Server Vuln | 2730 | -253 |

| CVE-2017-9841 | 2663 | -1823 |

| CVE-2020-8958 | 2354 | -2854 |

| CVE-2022-22947 | 2210 | 861 |

| CVE-2021-28481 | 1792 | 44 |

| CVE-2018-10561 | 1344 | -904 |

| CVE-2019-9082 | 659 | -794 |

| CVE-2017-18368 | 649 | -68 |

| CVE-2021-3129 | 623 | -661 |

| CVE-NETGEAR-MOZI | 466 | 22 |

| CVE-2021-26086 | 338 | -16 |

| CVE-2020-25078 | 305 | -240 |

| CVE-2019-18935 | 260 | 55 |

| CVE-2013-6397 | 238 | -604 |

| CVE-2021-44228 | 125 | -209 |

| CVE-2021-22986 | 96 | -32 |

| CVE-2021-41277 | 88 | -64 |

| CVE-2020-7796 | 18 | 10 |

| CVE-2018-7600 | 10 | -1 |

| CVE-2022-1388 | 6 | -21 |

| CVE-2020-3452 | 5 | -138 |

| CVE-2021-29203 | 4 | -15 |

| CVE-2022-22965 | 4 | -24 |

| CVE-2008-6668 | 3 | -8 |

| CVE-2017-0929 | 3 | -5 |

| CVE-2021-21315 | 3 | -9 |

| CVE-2021-32172 | 3 | -8 |

| CVE-2018-1000600 | 2 | -4 |

| CVE-2018-7700 | 2 | -7 |

| CVE-2019-2767 | 2 | -6 |

| CVE-2020-28188 | 2 | -7 |

| CVE-2020-9757 | 2 | -18 |

| CVE-2021-33357 | 2 | -6 |

| CVE-2021-3577 | 2 | -9 |

| CVE-2022-25369 | 2 | -11 |

| CVE-2019-8982 | 1 | -7 |

| CVE-2020-13167 | 1 | -6 |

Table 1. CVE targeting volume for September, along with traffic change from August.

Targeting Trends

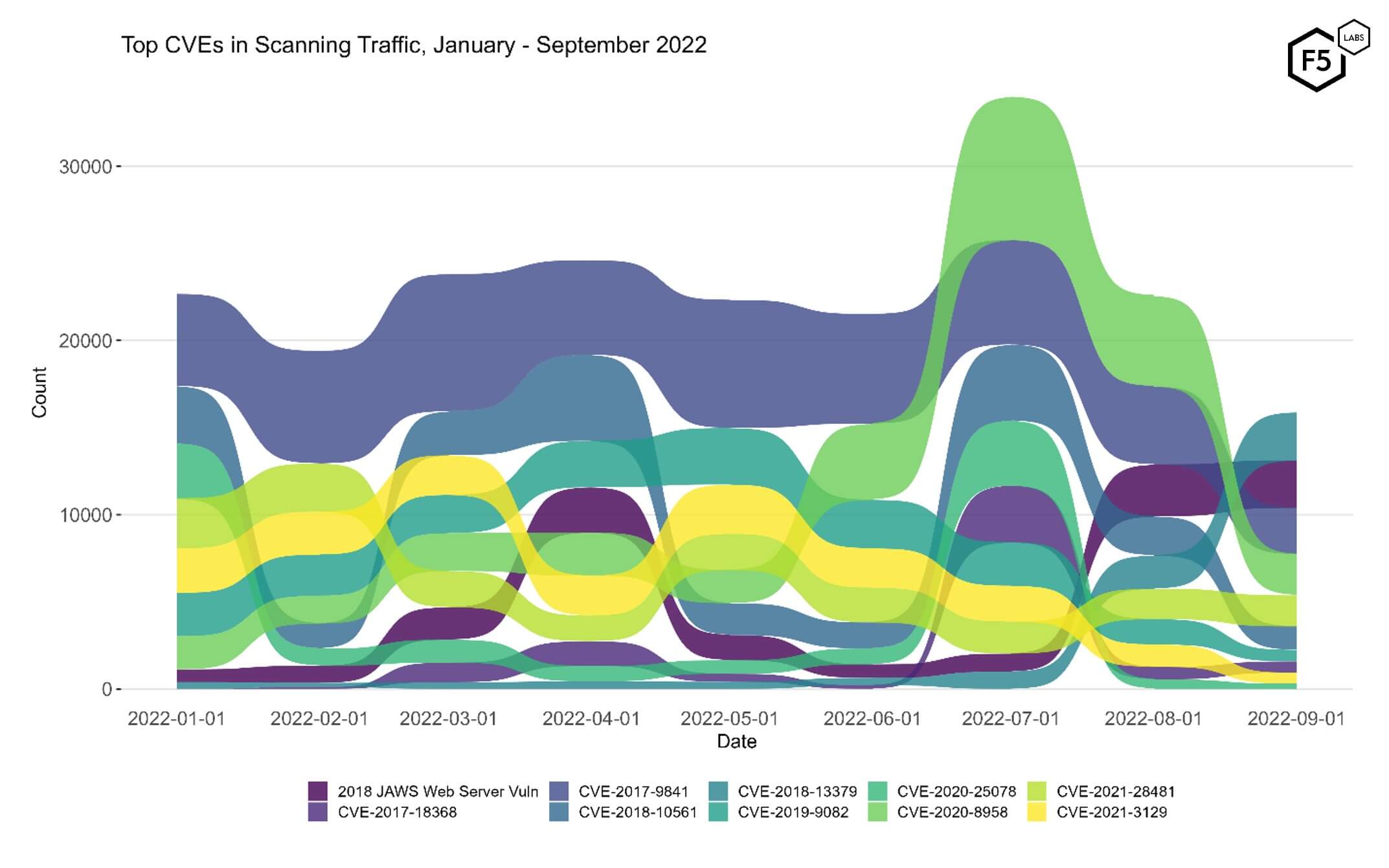

To get a sense of the change in targeting over time, Figure 2 shows a bump plot of the top vulnerabilities over the course of 2022. Like the bump plot from August (and unlike earlier plots in this series), this plot shows traffic over time for a subset of the total vulnerabilities because the full plot became too difficult to read as we added more and more vulnerabilities. There are ten vulnerabilities shown here, which collectively constitute the top five of each month.

Figure 2. Evolution of vulnerability targeting, January-September 2022. While the emergence of CVE-2018-13379 in our data is interesting, it also occurred in concert with an overall dip in traffic for September.

There are several interesting developments in this plot other than the emphasis on CVE-2018-13379, the vulnerability in the Fortinet SSL VPNs . After growing in prominence to second rank in June and occupying top spot in July and August, CVE-2020-8958 dropped in attack frequency in September to occupy the fourth spot. September was also the first month in this period in which CVE-2017-9841 dropped below the second rank.

All of these trends, however, should be seen in light of the overall drop in traffic targeting CVEs. Both the overall traffic and the vulnerability-focused traffic were below the monthly average. We don’t know if it is because attackers are directing their efforts elsewhere (either in terms of targets or methods), or if some attacker infrastructure was taken down, but the most heavily targeted CVE in September had only a third of the traffic that the top CVE had in July.

Identifying Rapid Growth

The most interesting question around vulnerability trends over time is rapid growth. Most of the CVEs we track fall into one of two clusters of traffic: less than ten attacks or scans per month, which makes up the bulk of the vulnerabilities, and a smaller group that are targeted between 100 and 10,000 times per months. Occasionally we see a vulnerability jump in frequency from one to the other, and when that happens, the next most interesting question is whether the attacker attention endures over time or drops off.

| CVE-2020-8958 A command injection vulnerability in Guangzhou 1GE ONU V2801RW 1.9.1-181203 through 2.9.0-181024 and in V2804RGW 1.9.1-181203 through 2.9.0-101024 which allowed remote attackers to execute arbitrary OS commands. The vast majority of observed traffic targeting 2020-8958 was simple requests to identify possibly vulnerable endpoints, but a few were attempting to log in with simple credential pairs (such as admin/admin). NVD |

| CVE-2017-9841 A remote code execution (RCE) vulnerability in PHPUnit (4.x before 4.8.28 and 5.x before 5.6.3) that allows attackers to execute arbitrary PHP code on the target. The vast majority of the payloads observed in our data appeared to be checks for a vulnerable target, such as “<? md5(“phpunit”) ?>” or calls to run “uname”; however, in some cases we saw an attempt to download and install a PHP based webshell. NVD |