Proxies operate on the premise that they exist to forward requests from one system to another. They generally add some value – otherwise they wouldn’t be in the middle – like load balancing (scale), data leak prevention (security), or compression (performance).

The thing is that the request sent by the client is otherwise passed, unmodified, to its target destination.

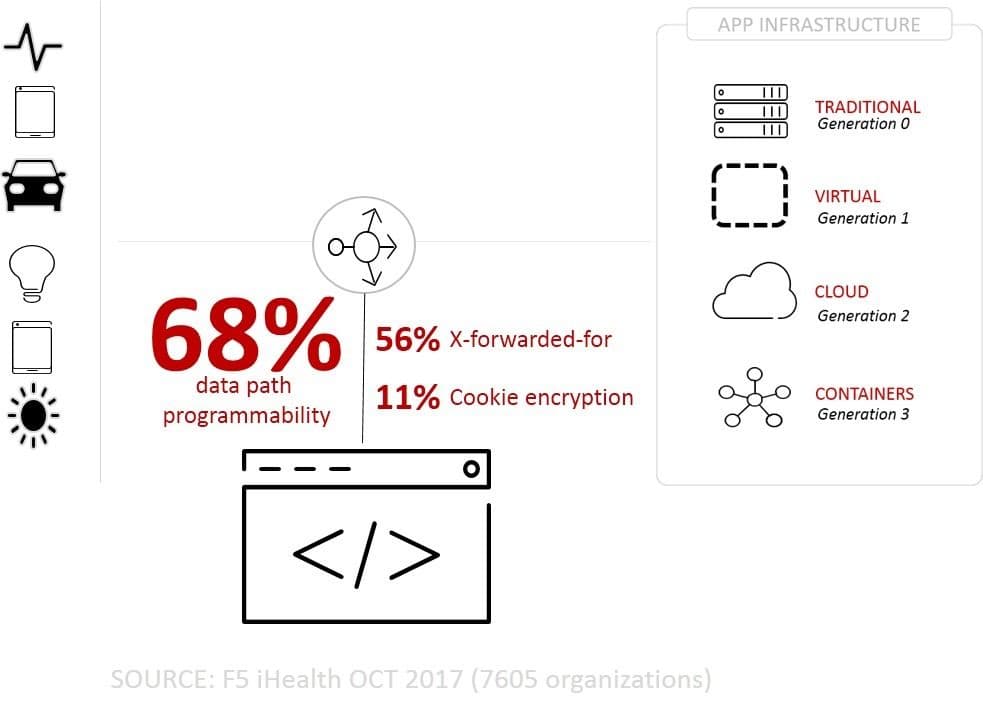

Here’s where things can get dicey. Today, we see more than half of all apps delivered via a proxy make use of X-Forwarded-For. 56% of real, live apps are using it, which makes it a pretty significant piece of data. X-Forwarded-For is the custom HTTP header that carries along the original IP address of a client so the app at the other end knows what it is. Otherwise it would only see the proxy IP address, and that makes some apps angry.

That’s because a good number of applications rely on knowing the actual IP address of a client to help prevent fraud and enable access. If you’ve logged into your bank, or Gmail, or your Xbox account lately (hey, it’s where Minecraft lives, okay?) from a device other than the one you typically use, you might have gotten a security warning. Because the information about where you log in from is also tracked, in part to detect attempted fraud and misuse.

Your actual IP address is also used to allow or deny access in some systems, and as a means of deducing your physical location. That’s why those e-mail warnings often include “was that you logging in from Bulgaria?”

Some systems also use X-Forwarded-For to enforce access control. WordPress, for example, uses the .htaccess file to allowlist access based on IP addresses. No, it’s not the best solution, but it’s a common one, and you have to at least give them props for trying to provide some app protection against misuse.

Irrespective of whether it’s a good idea or not, if you’re going to use X-Forwarded-For as part of your authentication or authorization scheme, you should probably make a best effort attempt to ensure it’s actually the real client IP address. It is one of the more commonly used factors in the overall security equation; one that protects the consumer as much as it does corporate interests.

But if you are blindly accepting whatever the client sends you in that header, you might be enabling someone to spoof the value and thereby bypass security mechanisms meant to prevent illegitimate access. I can spoof just about anything I want, after all, by writing a few lines of code or grabbing one of the many Chrome plug-ins that enables me to manipulate HTTP headers with ease.

One of the ways to ensure that you’re getting the actual IP address is to not trust user input. Yes, there’s that Security Rule Zero again. Never trust user input. And we know that HTTP headers are user input, whether they appear to be or not.

If you’ve got a proxy already, great. If not, you should get one. Because that’s how you extract and put the right value in X-Forwarded-For and stop spoofers in their tracks.

Basically, you want your proxy to be able to reach into a request and find the actual, IP address that’s hidden in its IP packet. Some proxies can do that with configuration or policies, others require some programmatic magic. However you get it, that’s the value you put into the X-Forwarded-For HTTP header, and proceed as normal. Doing so ensures that the apps or downstream services have accurate information on which to make their decisions, including those regarding access and authorization.

For most architectures and situations, this will mitigate the possibility of a spoofed X-Forwarded-For being used to gain unauthorized access. As always, the more pieces of information you have to form an accurate understanding of the client – and its legitimacy – the better your security. Combining IP address (in the X-Forwarded-For) with device type, user-agents, and other tidbits automatically carried along in HTTP and network protocols provides a more robust context in which to make an informed decision.

Stay safe!

Resources for handling X-Forwarded-For:

About the Author

Related Blog Posts

Why sub-optimal application delivery architecture costs more than you think

Discover the hidden performance, security, and operational costs of sub‑optimal application delivery—and how modern architectures address them.

Keyfactor + F5: Integrating digital trust in the F5 platform

By integrating digital trust solutions into F5 ADSP, Keyfactor and F5 redefine how organizations protect and deliver digital services at enterprise scale.

Architecting for AI: Secure, scalable, multicloud

Operationalize AI-era multicloud with F5 and Equinix. Explore scalable solutions for secure data flows, uniform policies, and governance across dynamic cloud environments.

Nutanix and F5 expand successful partnership to Kubernetes

Nutanix and F5 have a shared vision of simplifying IT management. The two are joining forces for a Kubernetes service that is backed by F5 NGINX Plus.

AppViewX + F5: Automating and orchestrating app delivery

As an F5 ADSP Select partner, AppViewX works with F5 to deliver a centralized orchestration solution to manage app services across distributed environments.

F5 NGINX Gateway Fabric is a certified solution for Red Hat OpenShift

F5 collaborates with Red Hat to deliver a solution that combines the high-performance app delivery of F5 NGINX with Red Hat OpenShift’s enterprise Kubernetes capabilities.