Fraud has become a pervasive part of the discussion around cybersecurity. In part, this reflects a change in attacker motives, as cyber-attacks were not always as vicious as they are now. From the 1980s into the early 2000s, hacking was not really about profit. It was primarily about achieving fame in the hacker community by demonstrating knowledge and insight about information systems, while also having a bit of fun. While many of the early high-profile hacks were indeed illegal and were prosecuted as such, they were also comparatively whimsical and harmless, except to the IT staff who had to clean up the networks afterward.1

By comparison, the present threat landscape is broken down into two significant approaches. Although other kinds of attackers exist, most significant attacks fall into one of two categories. One is nation-state actors, whose motivations primarily make up the espionage and (cyber)warfare portions of the CHEW model (/content/f5-labs-v2/en/labs/articles/bylines/chew-on-this--how-our-digital-lives-create-real-world-risks.html) of attacker motives. However, North Korean advanced attackers such as APT38 have notably included cybercrime in their repertoire to generate liquid funds for the heavily sanctioned and internationally isolated North Korean regime.2 The other mode is crime, which is incorporating an increasingly diverse set of fraud strategies into the cybercrime toolbox.3

Fraud is, accordingly, on everyone’s lips, but some misunderstandings about it threaten to blur the concept, which can make fraud look—erroneously—like a vague synonym for cybercrime itself. This does us no good, for two reasons: it overlooks the experience and knowledge in detecting and preventing fraud that other parties—law enforcement, financial institutions, and governments—have, and it makes it unclear exactly how to fight it.

This article is an attempt to clarify what forms digital fraud takes and to differentiate it from other attacker behaviors that are often related or adjacent to fraud. The goal here is to help security practitioners understand where antifraud efforts and security converge and where they diverge. So, no matter how any particular organization is structured, fraud teams and security teams can better understand their respective responsibilities, strengths, and weaknesses.

Defining Fraud

We start with the FBI’s definition of fraud, because it contains the key element we need to understand when a cyberattack is, or includes, fraud. The FBI defines fraud as:

The intentional perversion of the truth for the purpose of inducing another person or other entity in reliance upon it to part with something of value or to surrender a legal right. Fraudulent conversion and obtaining of money or property by false pretenses4.

Leaving aside the fact that the word fraudulent is part of the definition of fraud, this definition helps us because it emphasizes that fraud is a financial crime that hinges on a lie. Successful lying requires some kind of contact, some social interaction, even if the contact is abstract and digital in form.

This observation is key because it lets us quickly eliminate several things that are often fraud-adjacent and part of mitigating fraud but aren’t really fraud. Theft is chief among them. Stealing something usually means avoiding direct contact with your target; if there is no contact, there can’t really be a lie. This means that most credential theft, whether it takes the form of keylogger malware or exfiltrating hashed passwords, can’t be fraud, even though it is a precursor to fraud and part of the antifraud umbra. The same goes for most account takeover (ATO) attacks, although that is a gray area which we’ll touch on later. Enrichment of stolen data, such as cracking hashed passwords, is also fraud-adjacent but not fraud. Those passwords might be used for fraud in the future, but because they don’t involve any deception, they don’t fit our criteria.

These distinctions also illuminate some critical differences between cybercrime and real-world crime: in the real world, theft immediately results in a loss to the victim, even if an attacker hasn’t had time to monetize the theft. In the case of digital theft, the loss is not immediately apparent (even if the victim immediately knows the theft occurred, which is rare) and only materializes when fraud occurs. This distinction works in converse as well—not all digital theft is in pursuit of fraud. In the case of piracy or intellectual property theft, the path to extracting value from the stolen goods involves no contact at all. This distinction is part of the reason why understanding digital fraud is not intuitive.

Flavors of Untruth

Traditionally, when the world was a little smaller, and checking people’s stories was harder, fraud often hinged on fabricating a background, therefore misrepresenting the implicit financial risk of working with the fraudster. Even though the story is contemporary, fraudster Anna Sorokin’s success in impersonating a wealthy heiress in order to obtain lines of credit, both official and unofficial, is a surprisingly successful example.5 In contrast, most digital fraud is about impersonating another identity completely, not just fabricating a background. This takes the form of asserting that you are indeed the person whose name is on that payment card or who earned those air miles.

Although many subtypes of fraudulent attacks exist, and the following is not an exhaustive list, the lying that underpins fraud really has only three kinds of targets: customers (meaning the public), private organizations, and public organizations.

Lying to the Public

Fraud cases like these don’t refer to an event in which someone’s credit card number is used for a fraudulent transaction because, while the citizen is a victim of a crime, they aren’t the target for the lie. Fraud against regular people is really about things like:

- Dating fraud: This type of fraud tends to take one of two forms. One is the appearance of a young woman looking for a man who can transfer some funds to her, after which romance will, we are told, abound. The other form is fraudsters looking for “romantic partners” who don’t mind handing off a package to someone, that is, looking for mules. In both cases, a fraud ecosystem is built around identifying likely targets, preparing plausible-looking bank accounts to accept funds, and collecting dossiers of believable information, such as photographs (usually of young women), that can be used as bait.

- Wire fraud: This type straddles the line between defrauding the customer and defrauding the bank, but it is incumbent on the banking customer to confirm the wire instructions with the appropriate account and routing numbers; the bank’s ability to intervene is limited. The lie here is really about the validity of the financial account information, which is usually delivered in a spoofed email purporting to be from the receiving bank.

Lying to Private Organizations

These are fraud cases where an organization is defrauded, which means there is either a higher value to a singular fraud attempt or multiple, smaller on-going fraud attempts happening.

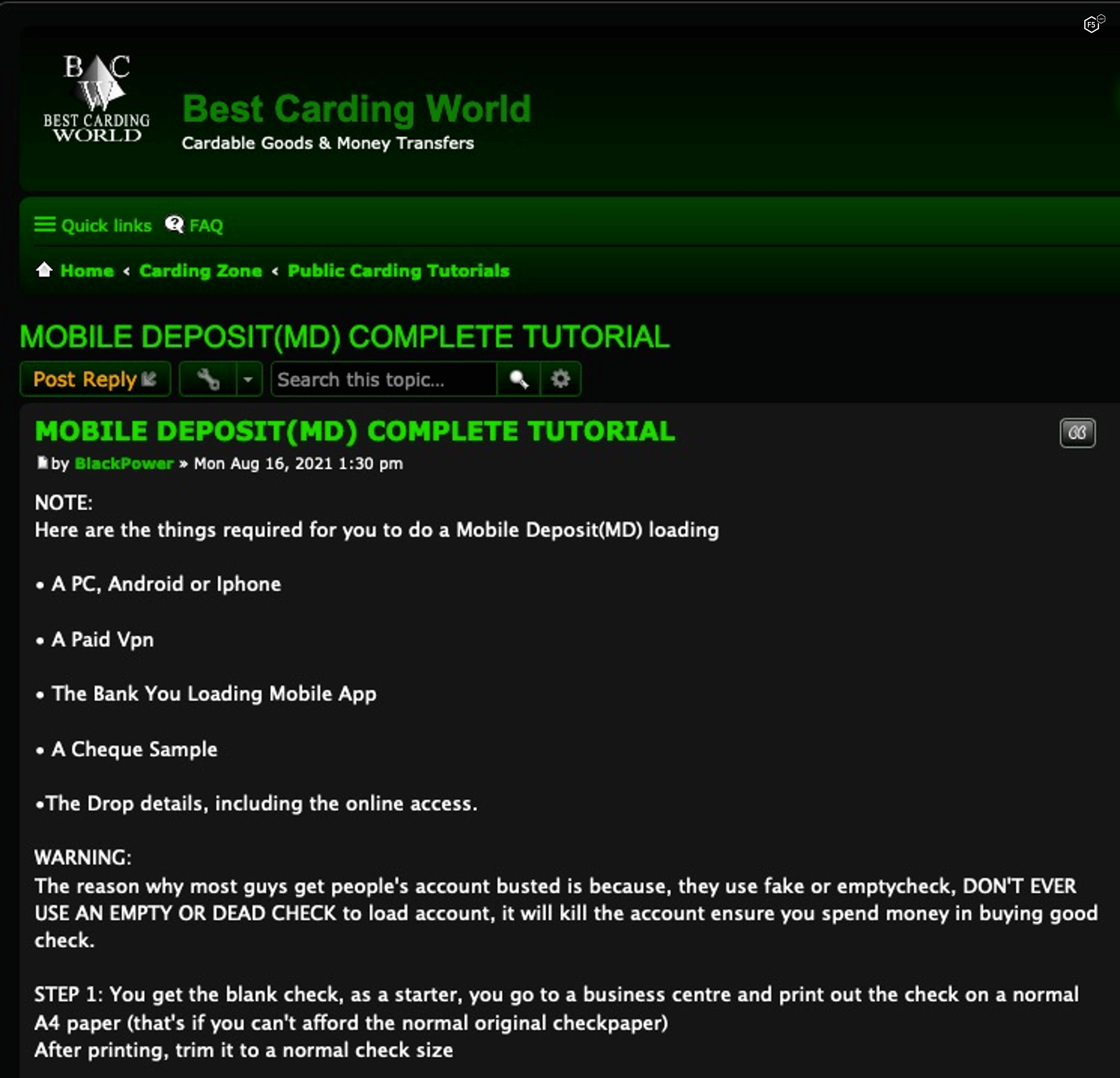

- Bank fraud: A lot of the fraud that happens around financial institutions is actually better understood as fraud against banking customers (discussed under “Wire fraud”) or fraud against retail organizations (more on that later). However, application fraud, in which attackers use stolen or spoofed personal information to open an account in a victim’s name, is an interesting example. Fraudulent bank accounts are used as logistical support for other criminal activities, such as money laundering or providing a landing place for funds from a dating fraud, as detailed earlier. Figure 1 shows a cybercriminal advertisement for bank fraud services for stolen banking information.

Figure 1. Screenshot of a tutorial for depositing fraudulent checks in a mobile banking app.

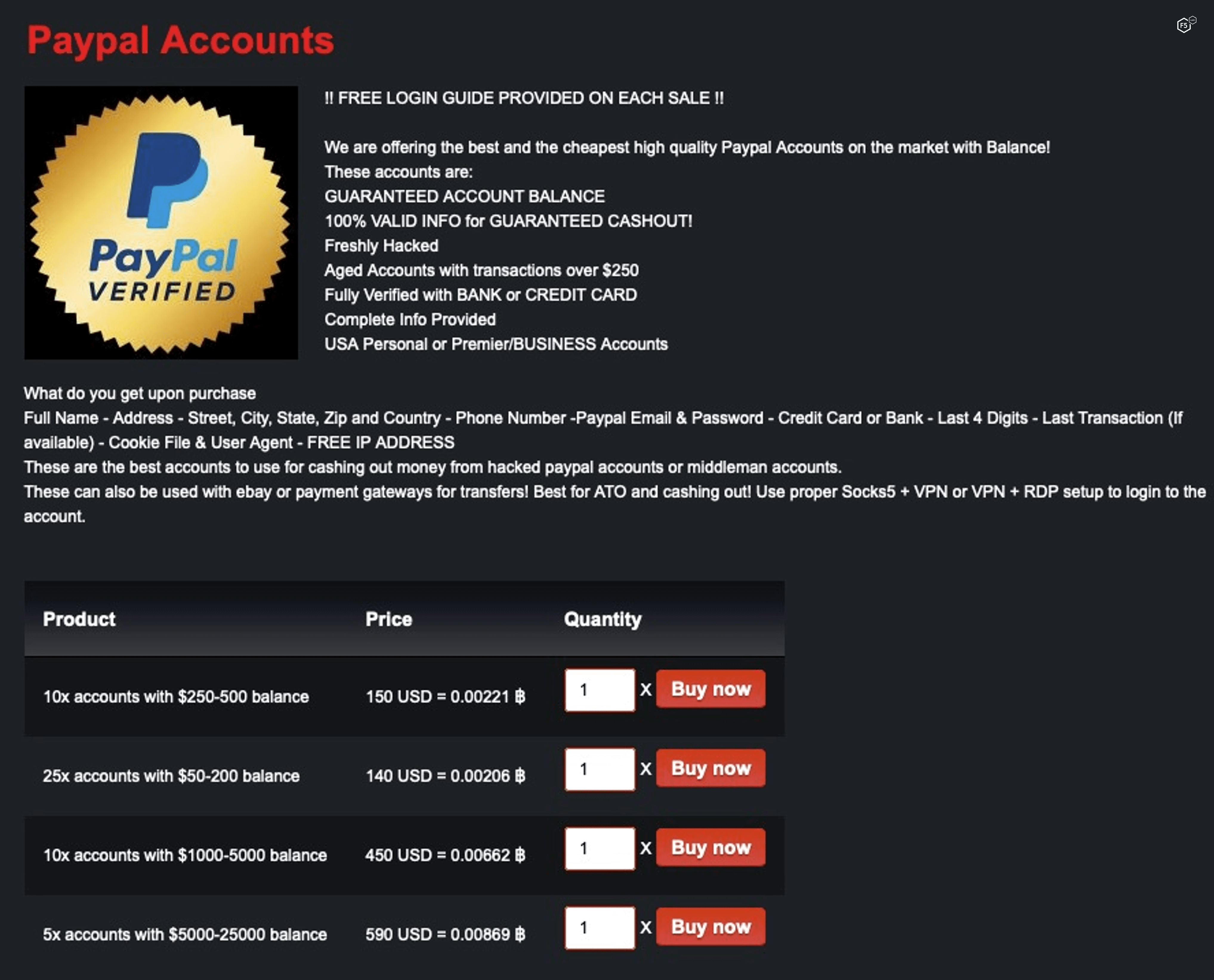

Another prevalent form of bank fraud has, as a precondition, an ATO attack. Brute force, credential stuffing, malware, and phishing can all play a role in the initial account takeover necessary for these kinds of attacks. After the takeover of a bank account, the attacker can make purchases or transfer funds to another account. In these kinds of attacks, maintaining control over a designated email address belonging to the customer can help attackers control communications between the bank and the customer, thereby maintaining better secrecy. Figure 2 is a cybercriminal advertisement for payment “cashout” services on the PayPal on stolen accounts from an ATO.

Figure 2. Compromised PayPal accounts for sale on the dark web.

- Retail fraud: A huge amount of the fraud discussion is around the use of stolen payment card information to make purchases. This kind of fraud is often listed under bank fraud, but since the retailer is responsible for vetting the buyer’s identity, they are the target of the lie, so we think it is better conceptualized as a form of retail fraud. Because of this responsibility, retail organizations are also the ones who bear the brunt in the event that the actual card owner requests a reversal of charges.

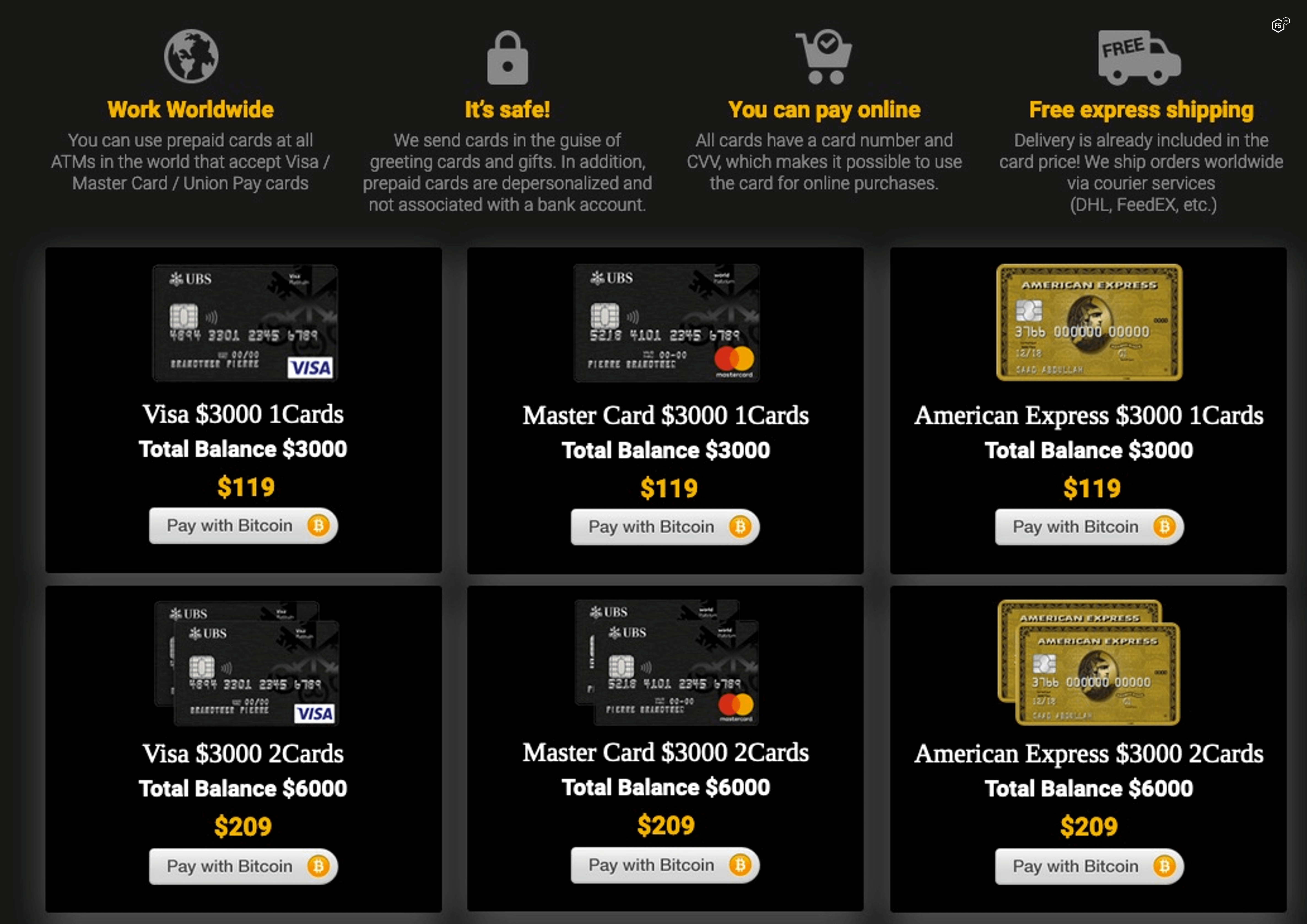

Numbers are difficult to come by on this subject, but it appears that this is one of the most damaging and prevalent forms of digital fraud. It is certainly a battlefield for an ongoing technical war between attackers and organizations seeking to use additional signals to help weed out malicious from benevolent users. As security organizations try to implement increasingly sophisticated fingerprinting techniques, attackers are turning to masquerading toolsets, such as antidetection browsers and digital identity marketplaces (/content/f5-labs-v2/en/labs/articles/threat-intelligence/genesis-marketplace--a-digital-fingerprint-darknet-store.html), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Screenshot of a dark web advertisement for compromised payment cards.

- Hospitality fraud: Observers of dark web activities have noted two sorts of fraud that involve hospitality, travel, or customer loyalty programs. One entails using fraudulent travel or accommodations services to harvest credentials and financial information for other use. This form belongs in the earlier section about fraud against the public. However, in another form of hospitality fraud organizations are targets of the lie. This involves using previously harvested loyalty points, air miles, rewards points, and the like for the purpose of booking travel services for others. Sometimes, the customers of the fraudulent service are aware of the source of their low prices—there are travel “agencies” in the attacker community that advertise travel services with the markdown from retail explicitly stated.

- SIM swaps: In this type of fraud, attackers gain control over mobile phone accounts by convincing mobile carriers to switch an account from one associated SIM card to another. While this is often enough for attackers to gain access to a core email account and perform ATO on subsidiary accounts, including banking apps, it is also important in that it can allow attackers to circumvent multifactor authentication that is routed to the phone. Some SIM swaps are done with the knowledge of local staff at a mobile carrier’s store, but many are the result of fraud.

Lying to Public Organizations

- Tax return fraud: The most high-profile digital fraud against public organizations is the filing of fraudulent tax returns. This is a specific form of identity theft. In this case, the attacker assumes the identity of an innocent member of the public, gains access to the necessary financial and demographic information, and files a return before the citizen can file their own.

These attacks require comparatively greater amounts of victim information prior to executing the attack. They are often broken up into disparate steps that are handled by specialists in different tasks, such as exfiltrating tax forms, gathering credentials to online tax preparation software, and laundering money afterward.

Special Mention: Phishing

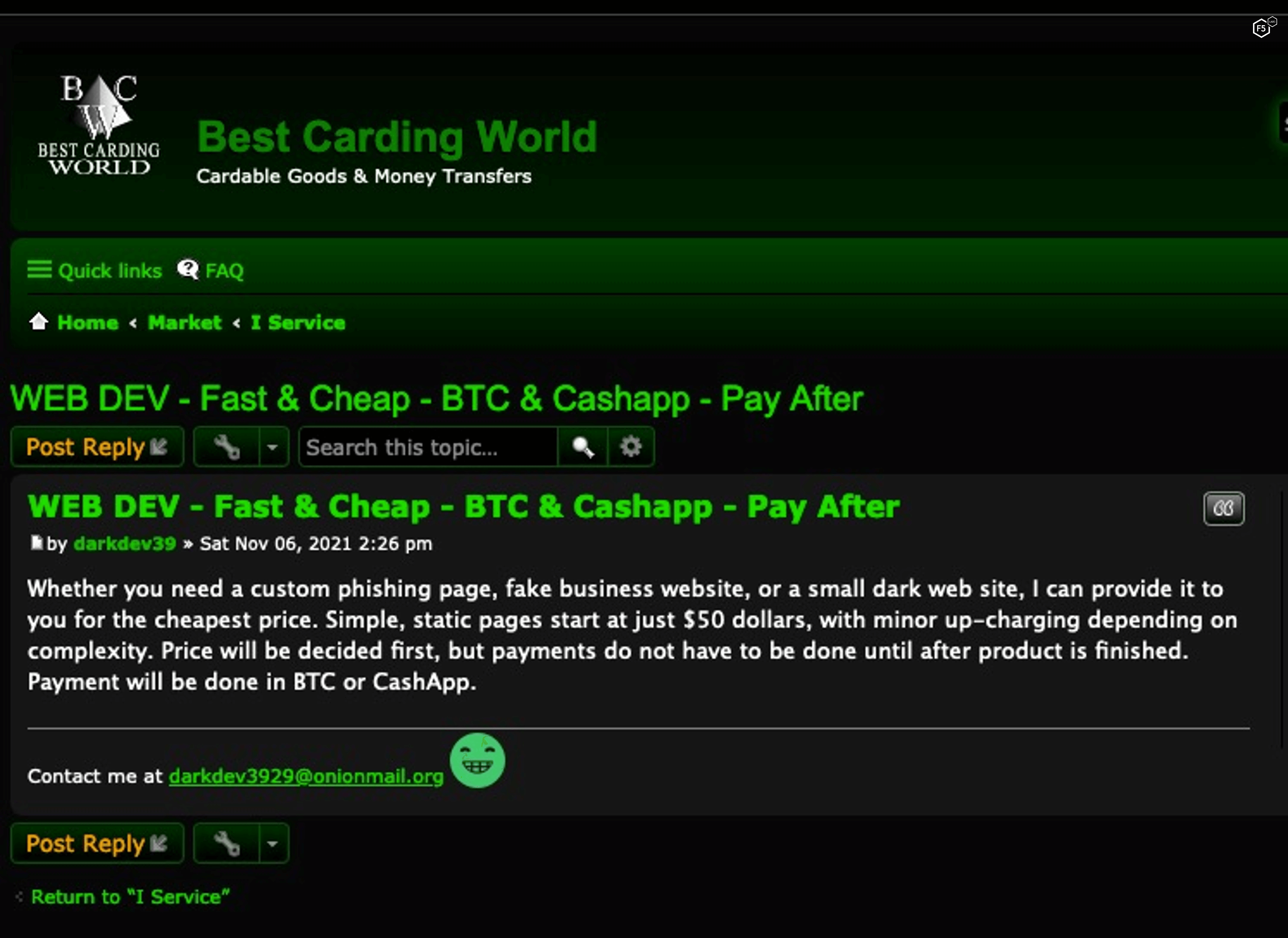

Phishing and other forms of technically dependent social engineering are interesting edge cases that hinge on your interpretation of the FBI’s phrase “something of value.” For the most part, phishing that does not deliver malware is used to harvest credentials, and while credentials aren’t exactly objects of currency, they are increasingly the only prerequisite for a host of digital financial activity, including ecommerce and online banking. Phishing is, therefore, fraud against a member of the public that is also a precondition for another form of fraud, usually against a private organization such as a bank or online retailer. Figure 4 shows a cybercriminal advertisement for phishing services to assist less cyber-savvy fraudsters.

Figure 4. Screenshot of a dark web advertisement for web development of a phishing site or similar spoofing sites.

Fraud-Adjacent Attacker Activities

It’s clear that many attacker activities that are part of the fraud ecosystem don’t have the characteristic element of untruth for profit that defines fraud. Much of this category makes up the bulk of what information security practitioners spend their days fighting. An inexhaustive list includes:

- Malware for stealing sensitive information: Importantly, this kind of attack doesn’t require any fraud (again, unless the malware was delivered by phishing) because it doesn’t involve any contact between attacker and victim.

- Money laundering: Money laundering is a big part of the attacker ecosystem, since it is key to attackers turning money into a form they can actually spend. It’s not fraud but does represent a fruitful potential avenue for law enforcement to disrupt the monetization process of fraud.

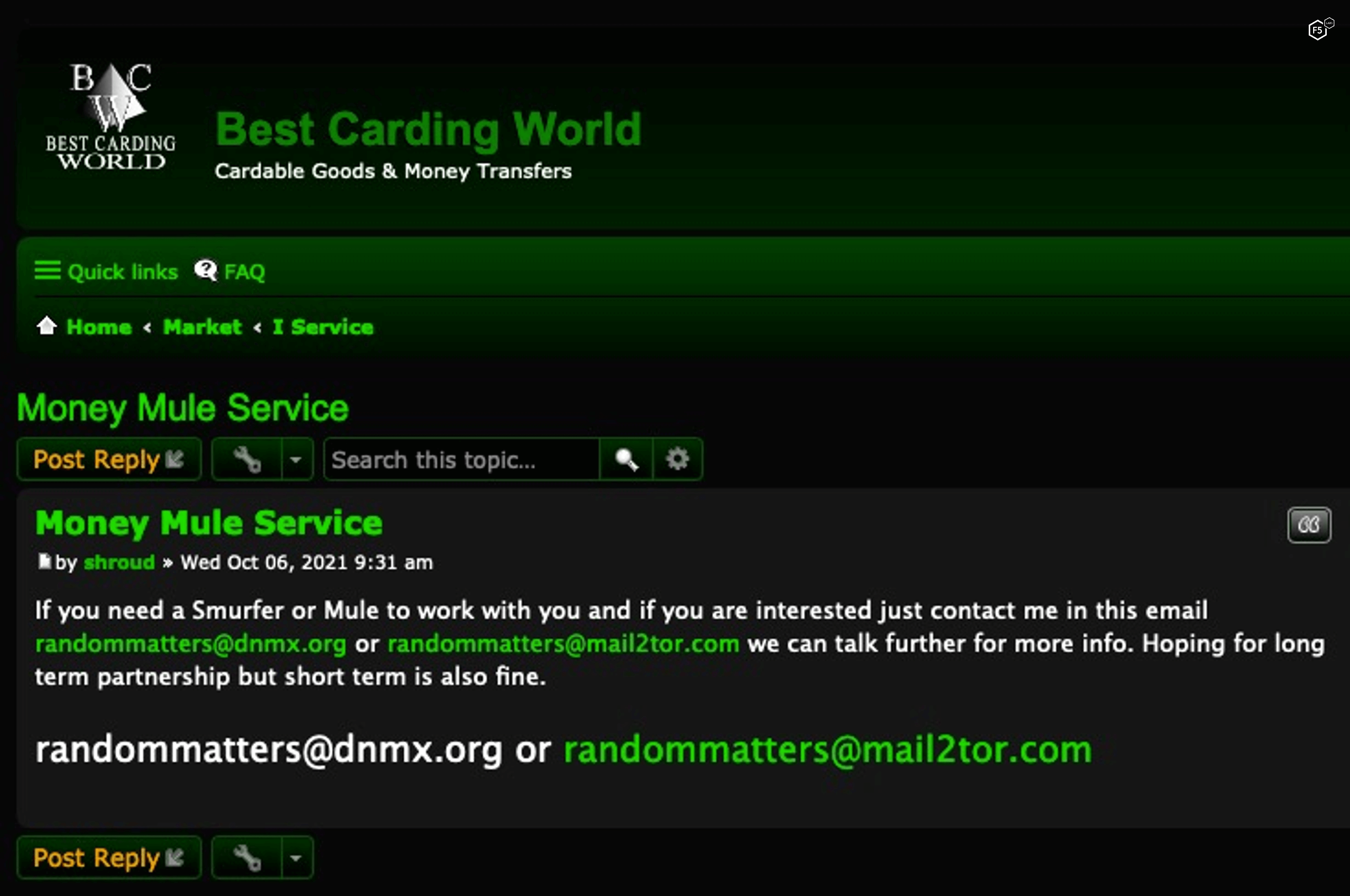

- Transport, drops, and mules: Just as with money laundering, these are crucial parts of the whole fraud ecosystem that don’t involve contact with a victim, except in the case of unwitting mules (see Figure 5), many of whom are recruited via dating scams.

Figure 5. Screenshot of a dark web advertisement for mule services.

- Attacker training: The attacker community has a rich training economy. Here, more experienced actors train newcomers in the various aspects of fraud—both the actual fraudulent contacts previously discussed and the fraud-adjacent logistical items listed in this section. This is particularly interesting because it represents a monetization path for attackers that depends on, but is separate from, actual fraud. This is the attacker community paying the attacker community for services, which makes the value of any actual fraud higher, but without any sort of contact.

- Account takeover: ATO that happens via brute force or credential stuffing is a huge part of the threat landscape and a significant challenge for organizations to mitigate (along with phishing, discussed earlier). One important thing to note when discussing ATO as a fraud-support mechanism is the degree to which this kind of attack is becoming a specialized service that attackers outsource to experts. The growing sophistication and diversification of the attacker economy could potentially tip the scales temporarily in attackers’ favor as ATO best practices become more widely disseminated.

Conclusion

We’ve spent as much time talking about what fraud is not as we have talking about what it is. This is because, while fraud is everywhere, all attacks are not themselves fraud. So why does that matter? Are we just splitting hairs?

It matters for two reasons. One reason is organizational. As awareness about digital fraud has grown, security teams increasingly find themselves working closely with fraud teams, but the architecture of these teams, and the delineation of responsibilities therein, varies widely. We’ve spoken to CISOs who have a fraud team under them. We’ve spoken to technical security experts who are embedded in fraud departments that report to the CFO. In the middle are organizations that have both teams but no formal junction, who have to collaborate to mitigate the threat. And, of course, lots of organizations with a small security team but no fraud team.

Because of this variability, it is important to understand how different kinds of attacks relate to one another to leverage different kinds of expertise. Fraud teams have a greater understanding of the ways that digital and nondigital criminal behaviors intersect as well as a better big-picture understanding of the impacts of financial crime. Security teams have a greater understanding of what they can accomplish with technical controls, whether they are preventive, detective, or corrective. Perhaps even more importantly, they understand the limitations of those controls.

The second reason it is important to understand what fraud is not is that it helps us better understand the characteristics of attacker monetization. Many of the ways that attackers monetize attacks don’t involve fraud but instead involve offloading what they stole to a specialist in another arena. A network intrusion specialist might sell hashed passwords to a cracking specialist. A web exploit specialist might sell a foothold in an enterprise network to a malware specialist, and so on. This kind of internal value-generation is difficult to detect in a tactically meaningful way; it also means that information that might not appear sensitive or valuable on the surface might be enriched into something very useful to attackers. Some attack chains start with the fraud and end several steps later with monetization. Some start with several other kinds of attacks, each of which features some monetization, with the fraud coming only at the end.

In sum, not all fraud is a monetization play in the short run, and not all monetization involves fraud. In a context where a great deal of attacker activity happens behind closed doors, fraud can be a clue to attackers’ proximate and long-term goals. Occasionally, the true victims of attacker activity on your network might be another organization’s customers’ customers. Understanding the ways that different attacker capabilities link up can help us put specific, observed behaviors into better context.