Welcome back to the Sensor Intelligence Series, our recurring monthly summary of vulnerability intelligence based on distributed passive sensor data. We’ll start off this month’s analysis with a look at some activity from the August dataset, which demonstrates some of the oddities we occasionally see, and then dig into the changes we saw in September for the CVEs we track.

First, an Aside From August

The sensors from which we gather Sensor Intel Series data are passive, meaning they do not have any DNS names associated with them, and that they do not respond to traffic. This means that most of the traffic we receive is broad, Internet-wide scanning activity, not particularly targeted to specific business or organization. Additionally, we’re focused on detecting attempts to exploit CVEs, so we typically don’t look very closely at traffic that isn’t targeting specific vulnerabilities.

It’s always a bit of a surprise when we see what looks like targeted activity. In preparation for this article, reviewing August 2023 data, we noticed an anomaly that was an interesting exception to the general rule.

Starting on August 15th, 2023, at 05:21 UTC, and ending on August 23rd, at 19:30 UTC, we saw a determined credential stuffing attack take place against one of our sensors located in Greece.

Over the course of these 8 days and 14 hours, we observed a steady stream of POST requests to the URI “/”, each containing the username of “root” or “admin” and a varying password string, most of which were only sent once. There wasn’t any indication of a particular software platform being targeted. The specific POST parameters which were used were “input_user”, “input_pass”, and “submit_login.”

This strikes us as notable for a few reasons. First, this traffic was seen on only one sensor. Secondly, it was relatively slow. Each request was separated from the next by 1 second or more. Third, the attack was sourced from a mere 18 IP addresses in just two ASNs. While there was some traffic observed from these IPs and ASNs targeting other sensors with other traffic, no other sensors saw this cred stuffing activity.

Table 1 shows the IPs and ASNs involved in this attack, along with the source and destination countries, and counts of traffic observed.

| Rank | Source IP | Source ASN | Source country | Destination country | Count |

| 1 | 94.66.207.186 | 6799 | Greece | Greece | 3685 |

| 2 | 188.161.195.114 | 12975 | Palestine | Greece | 1146 |

| 3 | 212.205.228.102 | 6799 | Greece | Greece | 951 |

| 4 | 94.65.86.163 | 6799 | Greece | Greece | 773 |

| 5 | 85.184.240.116 | 12975 | Palestine | Greece | 690 |

| 6 | 188.161.80.66 | 12975 | Palestine | Greece | 500 |

| 7 | 188.161.81.207 | 12975 | Palestine | Greece | 156 |

| 8 | 37.8.15.4 | 12975 | Palestine | Greece | 103 |

| 9 | 82.205.18.14 | 12975 | Palestine | Greece | 89 |

| 10 | 176.65.3.117 | 12975 | Palestine | Greece | 80 |

| 11 | 176.65.3.84 | 12975 | Palestine | Greece | 51 |

| 12 | 37.8.15.54 | 12975 | Palestine | Greece | 37 |

| 13 | 79.129.44.64 | 6799 | Greece | Greece | 15 |

| 14 | 85.184.241.237 | 12975 | Palestine | Greece | 14 |

| 15 | 82.205.7.4 | 12975 | Palestine | Greece | 8 |

| 16 | 176.65.3.49 | 12975 | Palestine | Greece | 4 |

| 17 | 82.205.28.48 | 12975 | Palestine | Greece | 3 |

| 18 | 82.205.18.146 | 12975 | Palestine | Greece | 1 |

Table 1: Source IP, Source ASN, Source Country, Destination Country, and traffic totals for a cred stuffing attack we observed between August 15

Once the attack ended, we didn’t see it again. In fact, we went back through all the 2023 data we have so far, and this specific pattern of cred stuffing attack only appears this once.

The biggest question we had was “Why would such a determined attack be launched at a sensor that wouldn’t ever respond?” In typical credential stuffing attacks, an attacker will monitor their results, looking for a “200 Success” or a “302 Redirect” response, or even just a size difference between successful and unsuccessful attempts, to be able to determine which username and password pair was valid. In this case, no responses whatsoever were seen by the attacker.

One possibility is that the attacker’s targeting was simply wrong. Perhaps they were targeting a netblock where they had identified a possibly valid target, and our sensor was caught up in an overly broad range of IPs. Perhaps they simply mistyped the target IP address, or used a DNS name which was incorrectly pointed towards our sensor. At the end of the day, we don’t have enough information to really say for certain.

Nevertheless, we did manage to capture some 6600 unique username and password pairs that this attacker used for their attempt and can now keep an eye out for more activity.

September Vulnerabilities by the Numbers

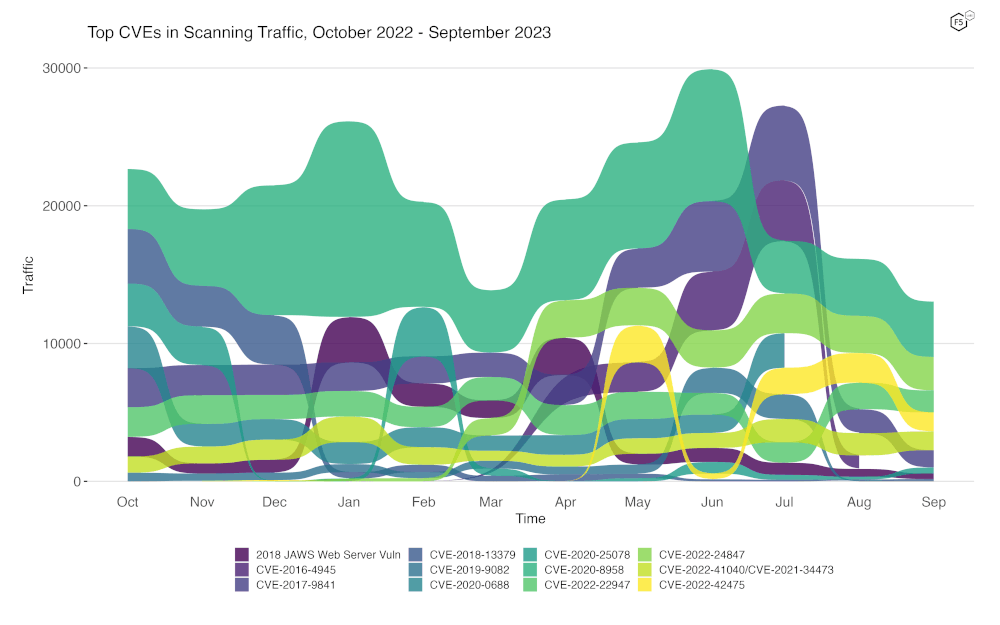

Figure 1 shows the traffic for the top 10 CVEs in September. CVE-2020-8958, a Guangzhou router command injection vulnerability, has been our top seen CVE for much of the past year, returning to the top last month, and continuing its dominance this month. Second place remained unchanged: CVE-2022-34847, an RCE in the open-source GeoServer software. In fact, only two of our top contenders changed their position this month. CVE-2022-42475, a heap-based buffer overflow in Fortinet SSL-VPNs dropped from 3rd to 4th position, and CVE-2017-9841, an RCE vulnerability in PHPUnit, dropped another position, continuing a downward trend we started observing in August. Overall traffic in the CVEs we track dropped again, but not as precipitously as it did in August.

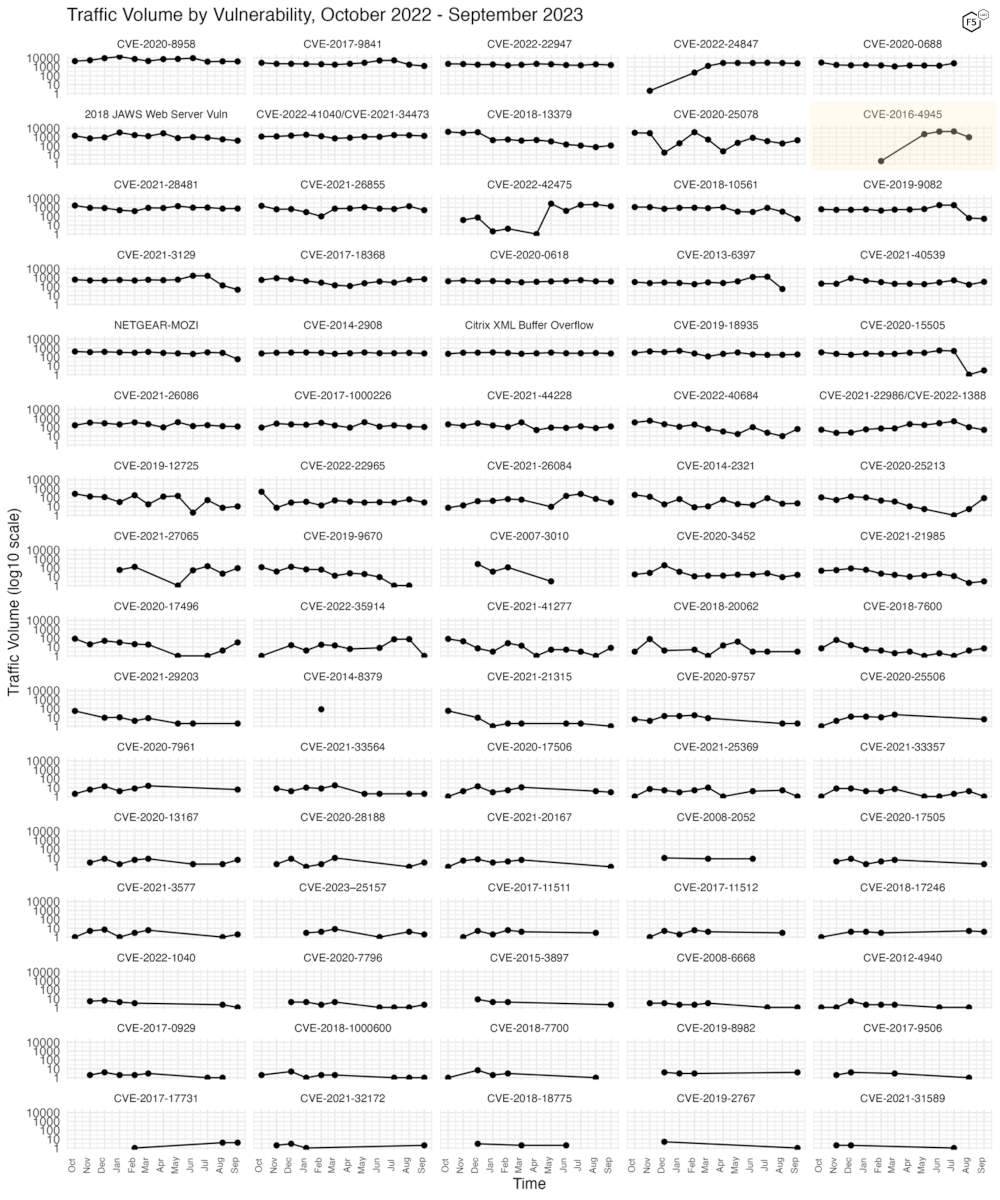

Table 2 shows traffic for September, change in traffic from August, CVSS v3.x score, and EPSS scores for 75 CVEs. Our list of CVEs with confirmed attack or scanning traffic currently stands at 81, but 6 vulnerabilities saw no traffic in either July or August and so don’t make this table.

| CVE Number | September Traffic | Change from August | CVSS v3.x | EPSS Score |

| CVE-2020-8958 | 4018 | -121 | 7.2 | 0.76447 |

| CVE-2022-24847 | 2424 | -270 | 7.2 | 0.00067 |

| CVE-2022-22947 | 1601 | -325 | 10 | 0.97498 |

| CVE-2022-42475 | 1371 | -782 | 9.8 | 0.38721 |

| CVE-2022-41040/CVE-2021-34473 | 1370 | -252 | 9.8 | 0.97342 |

| CVE-2017-9841 | 1243 | -494 | 9.8 | 0.97488 |

| CVE-2021-28481 | 747 | 7 | 9.8 | 0.04576 |

| CVE-2017-18368 | 697 | 117 | 9.8 | 0.97501 |

| CVE-2021-26855 | 492 | -883 | 9.8 | 0.97469 |

| CVE-2020-25078 | 442 | 249 | 7.5 | 0.96829 |

| 2018 JAWS Web Server Vuln | 402 | -167 | NA | NA |

| CVE-2020-0618 | 373 | -23 | 8.8 | 0.97355 |

| CVE-2021-40539 | 346 | 180 | 9.8 | 0.97422 |

| CVE-2014-2908 | 248 | -37 | NA | 0.00594 |

| Citrix XML Buffer Overflow | 243 | -35 | NA | NA |

| CVE-2019-18935 | 190 | 16 | 9.8 | 0.9352 |

| CVE-2021-44228 | 122 | 42 | 10 | 0.97472 |

| CVE-2021-26086 | 120 | -12 | 5.3 | 0.68779 |

| CVE-2018-13379 | 114 | 39 | 9.8 | 0.97418 |

| CVE-2017-1000226 | 106 | -15 | 5.3 | 0.00127 |

| CVE-2021-27065 | 92 | 70 | 7.8 | 0.96797 |

| CVE-2020-25213 | 85 | 80 | 9.8 | 0.97359 |

| CVE-2022-40684 | 62 | 52 | 9.8 | 0.94428 |

| NETGEAR-MOZI | 55 | -229 | NA | NA |

| CVE-2019-9082 | 53 | -11 | 8.8 | 0.97471 |

| CVE-2018-10561 | 52 | -281 | 9.8 | 0.97399 |

| CVE-2021-22986 | 46 | -23 | 9.8 | 0.97421 |

| CVE-2022-1388 | 4 | -15 | 9.8 | 0.97139 |

| CVE-2021-3129 | 45 | -91 | 9.8 | 0.97512 |

| CVE-2020-17496 | 33 | 29 | 9.8 | 0.97451 |

| CVE-2021-26084 | 29 | -41 | 9.8 | 0.97245 |

| CVE-2022-22965 | 28 | -34 | 9.8 | 0.97483 |

| CVE-2014-2321 | 22 | 2 | NA | 0.96364 |

| CVE-2020-3452 | 16 | 7 | 7.5 | 0.97545 |

| CVE-2019-12725 | 10 | 3 | 9.8 | 0.9653 |

| CVE-2021-41277 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 0.11624 |

| CVE-2018-7600 | 7 | 3 | 9.8 | 0.9756 |

| CVE-2020-13167 | 6 | 4 | 9.8 | 0.97407 |

| CVE-2020-25506 | 6 | 6 | 9.8 | 0.97435 |

| CVE-2020-7961 | 6 | 6 | 9.8 | 0.97443 |

| CVE-2017-17731 | 4 | 0 | 9.8 | 0.14043 |

| CVE-2018-17246 | 4 | -1 | 9.8 | 0.96913 |

| CVE-2019-8982 | 4 | 4 | 9.8 | 0.02146 |

| CVE-2018-20062 | 3 | 3 | 9.8 | 0.96823 |

| CVE-2020-15505 | 3 | 2 | 9.8 | 0.9749 |

| CVE-2020-17506 | 3 | -1 | 9.8 | 0.96091 |

| CVE-2020-28188 | 3 | 2 | 9.8 | 0.9724 |

| CVE-2021-21985 | 3 | 1 | 9.8 | 0.9737 |

| CVE-2015-3897 | 2 | 2 | NA | 0.83225 |

| CVE-2020-17505 | 2 | 2 | 8.8 | 0.96839 |

| CVE-2020-7796 | 2 | 1 | 9.8 | 0.72496 |

| CVE-2020-9757 | 2 | 0 | 9.8 | 0.96999 |

| CVE-2021-29203 | 2 | 2 | 9.8 | 0.95703 |

| CVE-2021-32172 | 2 | 2 | 9.8 | 0.26193 |

| CVE-2021-33564 | 2 | 0 | 9.8 | 0.07998 |

| CVE-2021-3577 | 2 | 1 | 8.8 | 0.97098 |

| CVE-2023-25157 | 2 | -2 | 9.8 | 0.39765 |

| CVE-2008-6668 | 1 | 1 | NA | 0.00359 |

| CVE-2018-1000600 | 1 | 0 | 8.8 | 0.95579 |

| CVE-2019-2767 | 1 | 1 | 7.2 | 0.14972 |

| CVE-2021-20167 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0.95111 |

| CVE-2021-21315 | 1 | 1 | 7.8 | 0.96857 |

| CVE-2021-25369 | 1 | -4 | 6.2 | 0.00118 |

| CVE-2021-33357 | 1 | -3 | 9.8 | 0.96791 |

| CVE-2022-1040 | 1 | -1 | 9.8 | 0.97277 |

| CVE-2022-35914 | 1 | -76 | 9.8 | 0.96777 |

| CVE-2012-4940 | 0 | -1 | NA | 0.04527 |

| CVE-2013-6397 | 0 | -54 | NA | 0.65834 |

| CVE-2016-4945 | 0 | -976 | 6.1 | 0.00204 |

| CVE-2017-0929 | 0 | -1 | 7.5 | 0.03588 |

| CVE-2017-11511 | 0 | -3 | 7.5 | 0.3318 |

| CVE-2017-11512 | 0 | -3 | 7.5 | 0.97175 |

| CVE-2017-9506 | 0 | -1 | 6.1 | 0.00575 |

| CVE-2018-7700 | 0 | -1 | 8.8 | 0.73235 |

| CVE-2019-9670 | 0 | -1 | 9.8 | 0.97147 |

Table 2. September traffic, change from August, CVSS and EPSS scores for 75 CVEs.

Targeting Trends

To better assess rapid changes in attack traffic, Figure 2 shows a bump plot, which plots both traffic volume and changes in rank. The 12 CVEs shown here represent the top five for each of the twelve months. Notable in this month’s plot is the complete lack of observed activity for CVE-2016-4945. Last month we observed its dramatic drop, and this month, it simply disappeared.

Figure 2. Evolution of vulnerability targeting trends over previous twelve months. Note the sharp stop of traffic for CVE-2016-4945.

It turns out that this traffic was only seen from one IP address, 68.1.19.59, an IP out of ASN 22773 in the United States. It first emerged in March 2023, scaled up its scanning over several months and peaked in July, and now, seems to have been taken down or stopped on its own accord on August 7th, 2023.

The last several months of observations really show how even modest changes in scanning activity can affect the overall traffic patterns we observe. A single IP, scanning broadly and quickly across the whole internet, can generate a significant amount of traffic.

Long Term Trends

Because Figure 2 only shows high-traffic CVEs, Figure 3 shows traffic for all 81 CVEs we have tracked. In this view, most of our tracked CVEs can be seen to be holding at a relatively steady rate, with a few others dropping off from relatively low volume in previous months, such as CVE-2022-36914, an RCE vulnerability in Teclib GLPI.

Figure 3. Traffic volume for the last twelve months for 81 tracked CVEs.

Conclusions

This month we added a signature for CVE-2020-0618, a remote code execution vulnerability in Microsoft SQL Server Reporting Services, and observed CVE-2016-4945 fall completely out of our data.

Our sensors are passive, and they do not respond to requests, nor do they pretend to be any specific platform or software stack. They are simply an open socket on port 80 and 443, with just enough of a webserver to be able to record the requests made to them and negotiate any required TLS connection. They do not have DNS names, although it’s certainly possible they may once have had them. Sometimes IP blocks are reassigned, and old DNS records remain that continue to point to them.

Given this, we expect to see traffic that is primarily composed of scanning and exploitation attempts that require little sophistication. Occasionally, however, we see other activity, such as the cred stuffing activity we analyzed this month.

Even with the above limitations, we can observe quite a lot, from the effects of an exploit being developed and shared for a new vulnerability, to the effect of an ISP taking down scanning infrastructure, if indeed this is what happened in the case of CVE-2016-4945.

In fact, the sudden disappearance of a CVE from our dataset does give some credence to the idea that reporting IP addresses we see conducting hostile activity to the ISPs responsible for them may lead to good outcomes. Certainly, some ISPs and hosting providers simply don’t care, and will take no action, but it is probably worth a try. It may not help you directly, but less hostile activity on the Internet seems to us to be a net benefit for all, although there are no guarantees that the hostile activity won’t reemerge.

For those new to the Sensor Intelligence Series, we will conclude by repeating some old but valid observations. We see a continuing focus on IoT and router vulnerabilities, as well as easy, essentially one-request remote code execution vulnerabilities. These typically result in the installation of malware, crypto miners, and DDoS bots. See you in November.

Recommendations

- Scan your environment for vulnerabilities aggressively.

- Patch high-priority vulnerabilities (defined however suits you) as soon as feasible.

- Engage a DDoS mitigation service to prevent the impact of DDoS on your organization.

- Use a WAF or similar tool to detect and stop web exploits.

- Monitor anomalous outbound traffic to detect devices in your environment that are participating in DDoS attacks.