The Sensor Intel Series is created in partnership with Efflux , who maintains a globally distributed network of sensors from which we derive attack telemetry.

---------------------------------------------------------------

Introduction

Welcome to the March 2024 installment of the Sensor Intelligence Series, our monthly summary of vulnerability intelligence based on distributed passive sensor data. This month’s attack data had one really big difference from what we usually see – we added a signature for CVE-2023-1389 and found that it was our top scanned for vulnerability and had been on the rise for the last several months!

Newly tracked vulns include:

- CVE-2023-1389, a command injection vulnerability in the firmware for the TP-Link Archer AX21 Wi-Fi router (CVSS 8.8, EPSS 92.7%)1

- CVE-2009-3960, an unspecified information disclosure vulnerability in the BlazeDS 3.2 library used by several Adobe products (CVSS v2 4.3, EPSS 99.68%)2

- CVE-2014-9792, a privilege escalation vulnerability in a Qualcomm component for Android devices (CVSS 7.8, EPSS n/a)3

- CVE-2020-28188, a remote code execution vulnerability in the TerraMaster TOS software. We already have been tracking this, but we added a new signature for another vector for exploiting this. (CVSS 9.8, EPSS 99.9%)4

- CVE-2022-47945, a local file inclusion vulnerability in the ThinkPHP framework (CVSS 9.8, EPSS 92%)5

March Vulnerabilities by the Numbers

Figure 1 shows March attack traffic for the top ten CVEs that we track. Note the emergence of CVE-2023-1389 at the top. Once we found a good signature for this vulnerability, we found that it’s activity pattern over the last year had been quite low, but present, in 2023, and suddenly jumped by several orders of magnitude in the last three months. Clearly, someone is targeting this WiFi router bug quite intentionally, likely to build out a bot net or other attacker infrastructure.

Our other top 10 entries are all ones we’ve seen before and are not showing a huge amount of variability.

Who is Scanning for CVE-2023-1389?

When we see such a distinct increase in scanning activity for a particular CVE, the next question is usually to figure out who is scanning for it, and where they’re targeting thier scans. Sometimes, we see a wide variety of IPs and source countries, and other times we see activity coming from a smaller subset of ASNs.

In this case, just two ASNs are generating the majority of the activity. The following chart shows the distribution of source ASNs for scans targeting CVE-2023-1389.

Meanwhile, the scans are distributed across a wide range of target countries:

The majority of the scanning activity is coming from IP addresses assigned to just a handful of ASNs, mostly AS49870 (Alsycon, a hosting provider out of the Netherlands) and AS47890 (Unmanaged Ltd, what looks to be an IT consulting firm based out of the UK). The scanners appear to be using VPS or other resources at these firms to conduct their activity.

After normalization for the number of sensors and other factors, the scanning activity looks to be quite evenly distributed across all the target countries listed above, each receiving approximately 3% of the total traffic, indicative of scanning casting an internet-wide net and attempting to find, in this case, as many vulnerable Wifi routers as possible.

Traffic Volume for Everything Else

Leaving the top ten, Table 1 shows traffic volumes for all vulnerabilities that we’re tracking, along with change from the previous month, CVSS score, and EPSS score. This month we’ve continued to include percent change in addition to the raw change. In terms of high-traffic CVEs, the percent change is usually more instructive. In terms of low-traffic CVEs where a fluctuation of a handful of connections makes for a change of hundreds of percent, raw traffic is more useful.

CVE Number March Traffic Change from February Percent Change CVSS v3.x EPSS Score CVE-2023-1389 3866 350 10.0% 8.8 0.92697 CVE-2020-11625 2688 -1044 -28.0% 5.3 0.46366 CVE-2022-24847 2377 47 2.0% 7.2 0.39902 CVE-2017-9841 2349 -206 -8.1% 9.8 0.99963 CVE-2022-22947 1876 -56 -2.9% 10 0.99973 CVE-2022-42475 1171 -6 -0.5% 9.8 0.9724 CVE-2020-8958 842 -695 -45.2% 7.2 0.98143 CVE-2022-41040/CVE-2021-34473 547 -104 -16.0% 9.8 0.99604 CVE-2021-3129 376 -327 -46.5% 9.8 0.99956 CVE-2020-0618 369 -34 -8.4% 8.8 0.99929 CVE-2021-28481 316 -160 -33.6% 9.8 0.92242 CVE-2018-13379 244 163 201.2% 9.8 0.99924 Citrix XML Buffer Overflow 222 -23 -9.4% NA n/a CVE-2014-2908 221 -21 -8.7% NA n/a CVE-2021-44228 186 -277 -59.8% 10 0.99998 CVE-2021-40539 140 -44 -23.9% 9.8 0.99977 CVE-2019-18935 139 -47 -25.3% 9.8 0.98961 CVE-2019-9082 134 -100 -42.7% 8.8 0.9995 CVE-2018-10561 128 22 20.8% 9.8 0.99773 CVE-2022-40684 122 122 0.0% 9.8 0.99792 2018 JAWS Web Server Vuln 94 54 135.0% NA n/a CVE-2017-1000226 93 -84 -47.5% 5.3 0.37937 CVE-2021-26855 93 -50 -35.0% 9.8 0.99981 CVE-2021-26086 91 -84 -48.0% 5.3 0.98875 NETGEAR-MOZI 82 -9 -9.9% NA n/a CVE-2020-25506 74 68 1133.3% 9.8 0.99903 CVE-2019-1653 66 -27 -29.0% 7.5 0.99999 CVE-2018-9995 59 -60 -50.4% 9.8 0.98747 CVE-2017-18368 48 46 2300.0% 9.8 0.99987 CVE-2022-47945 47 -172 -78.5% 9.8 0.92006 CVE-2014-2321 33 6 22.2% NA n/a CVE-2017-10271 18 -31 -63.3% 7.5 0.99934 CVE-2019-12725 9 -44 -83.0% 9.8 0.9952 CVE-2020-9757 8 8 0.0% 9.8 0.9958 CVE-2020-17496 7 1 16.7% 9.8 0.99968 CVE-2020-5902 7 -2 -22.2% 9.8 0.99998 CVE-2018-17246 6 6 0.0% 9.8 0.99618 CVE-2018-7600 6 -8 -57.1% 9.8 1 CVE-2019-2725 6 3 100.0% 9.8 1 CVE-2019-9670 6 5 500.0% 9.8 0.99968 CVE-2022-22965 6 0 0.0% 9.8 0.99973 CVE-2007-3010 5 5 0.0% NA n/a CVE-2020-25078 5 -61 -92.4% 7.5 0.98335 CVE-2020-28188 4 1 33.3% NA n/a CVE-2018-7700 4 4 0.0% 8.8 0.97473 CVE-2020-3452 4 4 0.0% 7.5 0.99981 CVE-2021-21985 4 1 33.3% 9.8 0.99921 CVE-2021-26084 4 -70 -94.6% 9.8 0.99946 CVE-2022-21587 4 1 33.3% 9.8 0.99881 CVE-2014-6287 2 -43 -95.6% 9.8 n/a CVE-2015-8813 2 2 0.0% 8.2 0.76191 CVE-2017-0929 2 2 0.0% 7.5 0.80646 CVE-2017-17731 2 2 0.0% 9.8 0.895 CVE-2018-1000600 2 2 0.0% 8.8 0.9902 CVE-2018-20062 2 0 0.0% 9.8 0.9963 CVE-2019-12988 2 -1 -33.3% 9.8 0.99842 CVE-2019-16057 2 -4 -66.7% 9.8 0.99986 CVE-2019-8982 2 2 0.0% 9.8 0.87753 CVE-2020-24949 2 2 0.0% 8.8 0.99339 CVE-2021-27065 2 2 0.0% 7.8 0.99524 CVE-2023–25157 2 -1 -33.3% 9.8 #N/A CVE-2020-15505 1 -2 -66.7% 9.8 0.99992 CVE-2005-3128 0 0 0.0% NA n/a CVE-2008-2052 0 0 0.0% NA n/a CVE-2008-6668 0 0 0.0% NA n/a CVE-2009-1872 0 0 0.0% NA n/a CVE-2011-4926 0 0 0.0% NA n/a CVE-2012-1823 0 0 0.0% NA n/a CVE-2012-4940 0 0 0.0% NA n/a CVE-2013-6397 0 0 0.0% NA n/a CVE-2014-4535 0 0 0.0% 6.1 n/a CVE-2014-9792 0 -34 -100.0% 7.8 n/a CVE-2015-3897 0 0 0.0% NA 0.98358 CVE-2015-4074 0 0 0.0% 7.5 0.78003 CVE-2016-1000149 0 0 0.0% 6.1 0.45187 CVE-2016-4945 0 0 0.0% 6.1 0.57722 CVE-2017-11511 0 0 0.0% 7.5 0.9694 CVE-2017-11512 0 0 0.0% 7.5 0.99796 CVE-2017-9506 0 0 0.0% 6.1 0.77543 CVE-2018-18775 0 0 0.0% 6.1 0.50454 CVE-2018-20463 0 0 0.0% 7.5 0.90846 CVE-2019-12987 0 -3 -100.0% 9.8 0.99842 CVE-2019-2588 0 0 0.0% 4.9 0.95728 CVE-2019-2767 0 0 0.0% 7.2 0.95687 CVE-2020-0688 0 0 0.0% 8.8 0.99896 CVE-2020-13167 0 -3 -100.0% 9.8 0.99919 CVE-2020-17453 0 0 0.0% 6.1 0.81798 CVE-2020-17505 0 0 0.0% 8.8 0.9945 CVE-2020-17506 0 0 0.0% 9.8 0.99442 CVE-2020-22211 0 0 0.0% 9.8 0.96264 CVE-2020-25213 0 -4 -100.0% 9.8 0.99912 CVE-2020-27982 0 0 0.0% 6.1 0.64562 CVE-2020-28188 0 -3 -100.0% 9.8 0.99856 CVE-2020-7796 0 0 0.0% 9.8 0.97966 CVE-2020-7961 0 -6 -100.0% 9.8 0.99959 CVE-2020-9344 0 0 0.0% 6.1 0.57856 CVE-2021-20167 0 0 0.0% 8 0.99229 CVE-2021-21315 0 0 0.0% 7.8 0.99826 CVE-2021-21801 0 0 0.0% 6.1 0.98225 CVE-2021-23394 0 -3 -100.0% 9.8 0.87221 CVE-2021-25003 0 -3 -100.0% 9.8 0.97734 CVE-2021-25369 0 -3 -100.0% 6.2 0.44972 CVE-2021-29203 0 0 0.0% 9.8 0.99322 CVE-2021-31589 0 0 0.0% 6.1 0.6825 CVE-2021-32172 0 -3 -100.0% 9.8 0.96666 CVE-2021-33357 0 -3 -100.0% 9.8 0.99572 CVE-2021-33564 0 -6 -100.0% 9.8 0.94009 CVE-2021-3577 0 0 0.0% 8.8 0.99459 CVE-2021-38702 0 0 0.0% 6.1 0.8259 CVE-2021-41277 0 -3 -100.0% 10 0.99367 CVE-2022-0653 0 0 0.0% 6.1 0.57952 CVE-2022-0885 0 -3 -100.0% 9.8 0.96749 CVE-2022-1040 0 -3 -100.0% 9.8 0.99939 CVE-2022-22954 0 0 0.0% 9.8 0.99941 CVE-2022-26134 0 -5 -100.0% 9.8 0.9999 CVE-2022-35914 0 -3 -100.0% 9.8 0.99914 CVE-2022-40734 0 0 0.0% 6.5 0.93965 CVE-2023-25651 0 0 0.0% 8 0.05456 Table 1. CVE targeting volumes for March, along with change from February.

Targeting Trends

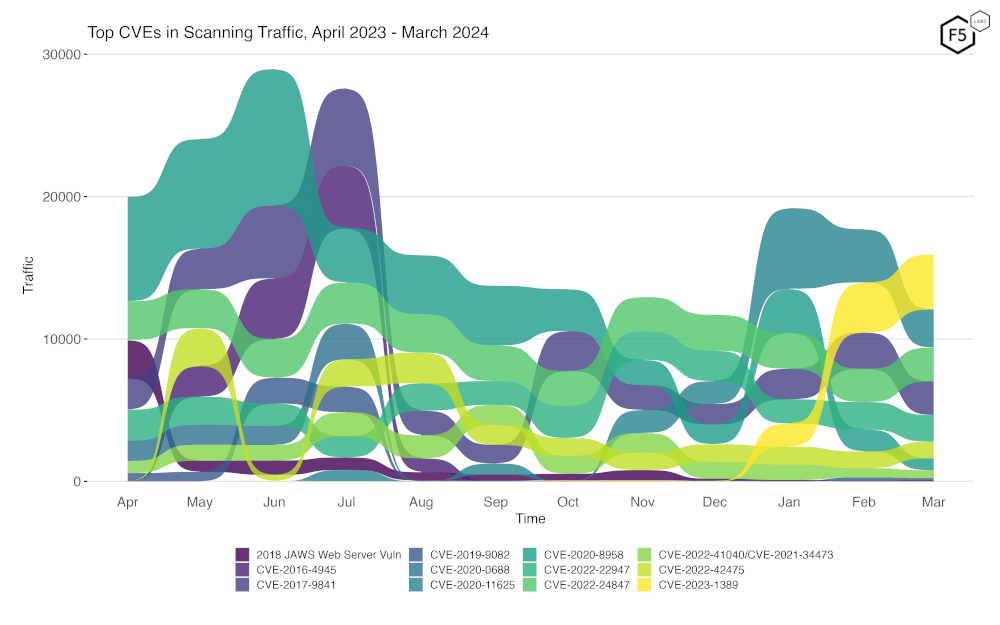

Figure 3 is a bump plot showing the change in traffic volume and position over the last twelve months. This shows very clearly the increase in scanning for CVE-2023-1389 since the start of the year. Also notable is the decrease in CVE-2020-11625, which had been in the top spot the last few months.

Figure 3. Evolution of vulnerability targeting in the last twelve months. Note the huge increase in scanning for CVE-2023-1389.

Long Term Trends

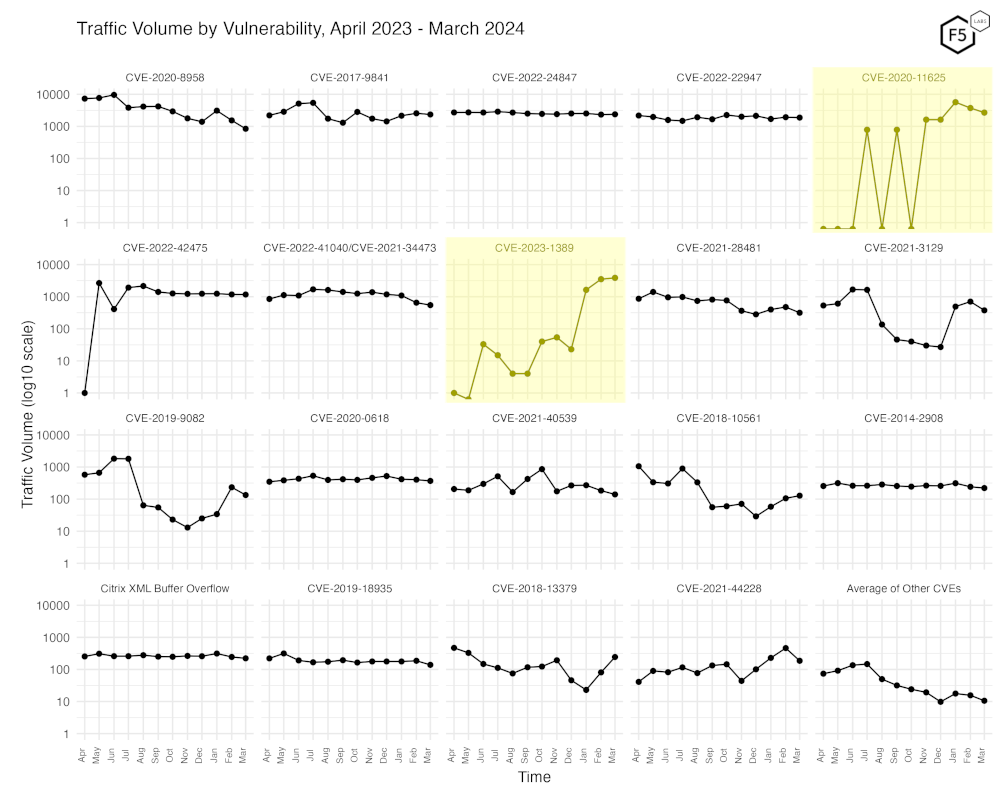

Figure 4 shows traffic for the top 19 CVEs by all-time traffic, followed by a monthly average of the remaining CVEs. This once again shows the dramatic increase in CVE-2023-1389, as well as the recent peaks of CVE-2020-11625.

Figure 4. Traffic volume by vulnerability. This view accentuates the recent growth in CVE-2023-1389.

Conclusions

We were able to identify much increased scanning traffic for CVE-2023-1389 and 3 other CVEs this month, as well as a better identification for one we already tracked, CVE-2020-28188. We continue to see much of this sort of bulk scanning traffic primarily being directed to what can be loosely called IoT devices, including WiFi routers. It’s quite clear to us that this is mainly a means for attackers to gather deniable infrastructure, which is unlikely to be shut down due to complaints to ISPs. The second most common pattern we see is targeting of what might be called “traditional server software” – and judging from the payloads we observe in these exploitation attempts, this too is often directed towards building out botnets (Mirai, Mozi) and occasionally the installation of other DDoS and crypto-mining bots.

Recommendations

- Scan your environment for vulnerabilities aggressively.

- Patch high-priority vulnerabilities (defined however suits you) as soon as feasible.

- Engage a DDoS mitigation service to prevent the impact of DDoS on your organization.

- Use a WAF or similar tool to detect and stop web exploits.

- Monitor anomalous outbound traffic to detect devices in your environment that are participating in DDoS attacks.