This blog, originally published on May 2, 2017, was updated September 21, 2017 based on new information obtained about Sabu’s activities following the revelation of his identity.

Spoiler alert! If you missed Part 1 of this blog series, you can catch up with the story here (/content/f5-labs/en/labs/articles/threat-intelligence/profile-of-a-hacker-the-real-sabu-part-1-of-2-26146.html), and find out what prompted The Jester to challenge the infamous hacker Sabu to reveal his true identity.

So, why did The Jester’s poolside taunts go unanswered by Sabu? As it turns out, by the time DEF CON 19 was well underway in Las Vegas (August 2011), Sabu had already been nabbed and turned by the FBI.

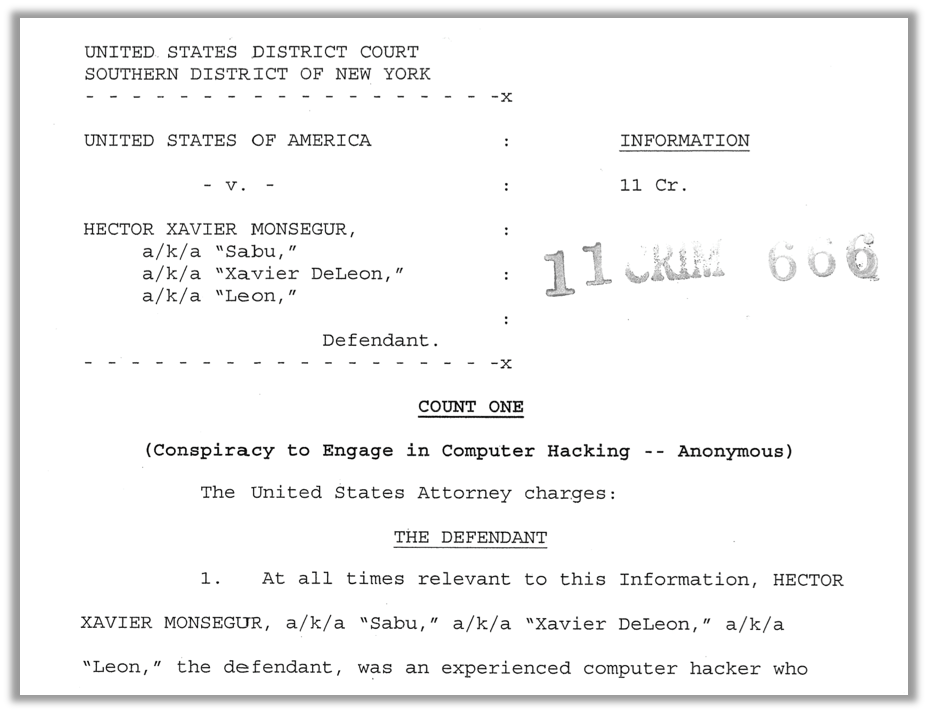

Court documents charging Hector Xavier Monsegur with conspiracy to engage in computer hacking1

There are multiple stories about how the capture of Sabu went down. The simplest one goes like this: Of course, Sabu used anonymization networks to hide his identity and make source tracing impossible. Network anonymization would have been a basic precaution for the most-wanted cybercriminal at the time.

There are several methods for anonymizing traffic. During LulzSec’s reign, one of the most talked about was a private VPN service called “HideMyAss” (HMA from here out). Another LulzSec member, “recursion,” used HMA and found out, to his detriment, that HMA was not in the business of shielding illegal activity; instead, it cooperated with law-enforcement authorities to identify him.2

Using hacked computers elsewhere on the Internet is another way to anonymize network traffic, and Sabu claimed to use them to hide his activities. He also claimed to use The Onion Router (Tor) network.3 Tor is the most famous anonymization network; it was originally developed by DARPA and is still partially funded by them today.

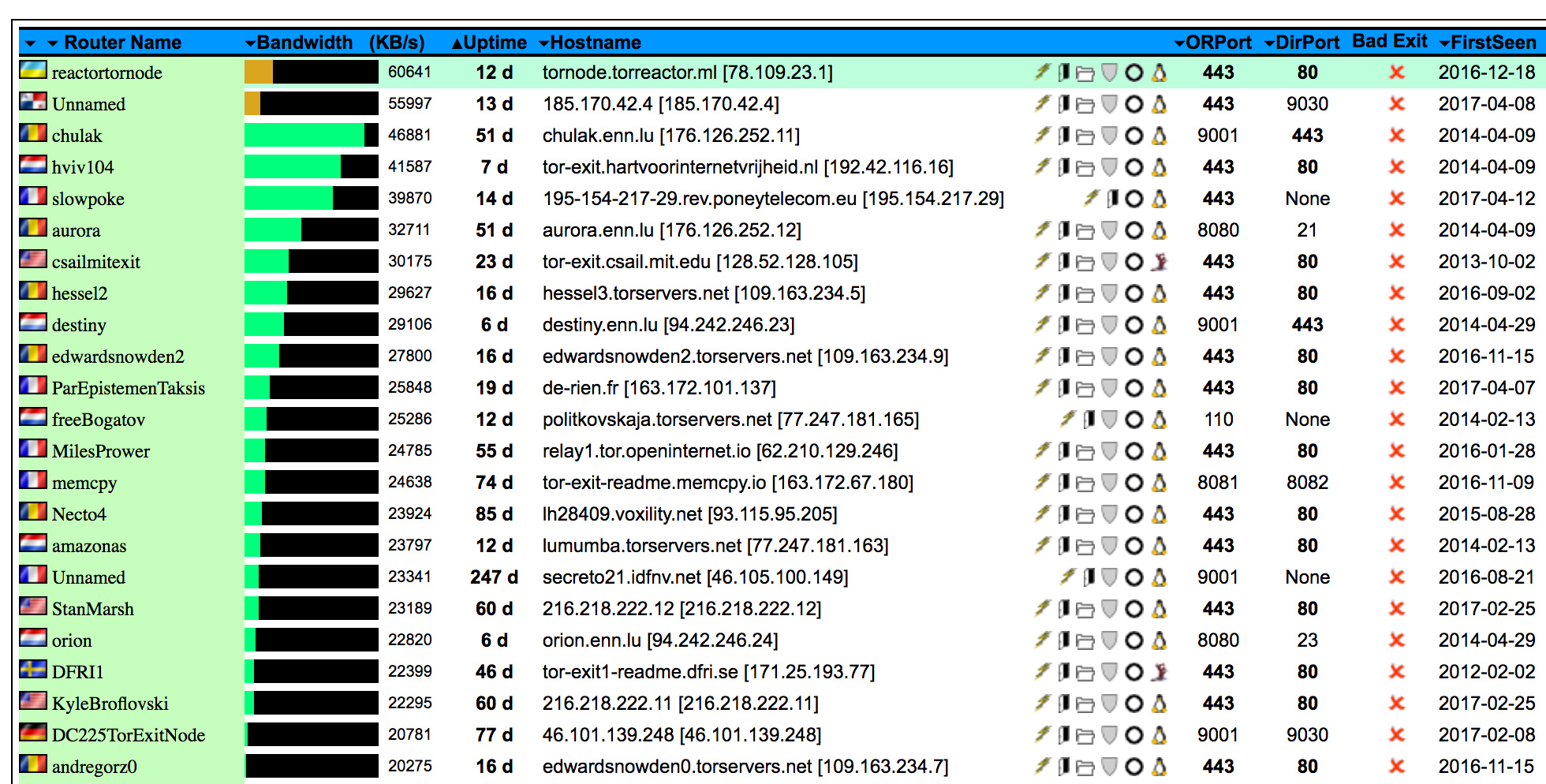

The Tor network consists of thousands of relay nodes all across the Internet, randomly relaying connections from clients through the Tor network and back out again. Most nodes simply relay encrypted connections to other nodes, but about one in ten allow the connection to “exit” out of the Tor network to the Internet.

Tor Network Status: Top Exit Nodes — https://torstatus.blutmagie.de/index.php

During LulzSec’s time, there were about 1,000 Tor exit nodes, and that number holds relatively steady today. This list is closely monitored and is included in most threat intelligence. Many organizations disallow traffic from Tor exit nodes unless they have a good reason (and there are few) to allow it.

But, back to Sabu. According to one story, Sabu forgot to activate his Tor link a single time,4 and logged into a server using his real IP address. Because he was the most-wanted cybercriminal at the time, his servers were almost certainly being watched by law enforcement. According to the story, the authorities traced his real IP address, and Sabu was quickly and quietly detained.

Sabu’s real name, as it turns out, was Hector Xavier Monsegur. He was born in New York city, but raised in Puerto Rico. The Puerto Rican island of Viecques, which was once used by the United States Navy for live fire training exercises, was one of his first interests as a hacktivist in 2000. Perhaps growing up near a bombing range was enough to inspire Monsegur to a life of Internet hacktivism. (Or perhaps he just did it for the Lulz, after all.)

Monsegur had been implicated in, or bragged about, dozens of illegal, high-profile hacks, not to mention multiple DDoS attacks. Facing a sentence of 25 to 100 years in prison, he struck a deal in which he agreed to turn over his friends from LulzSec to the authorities.

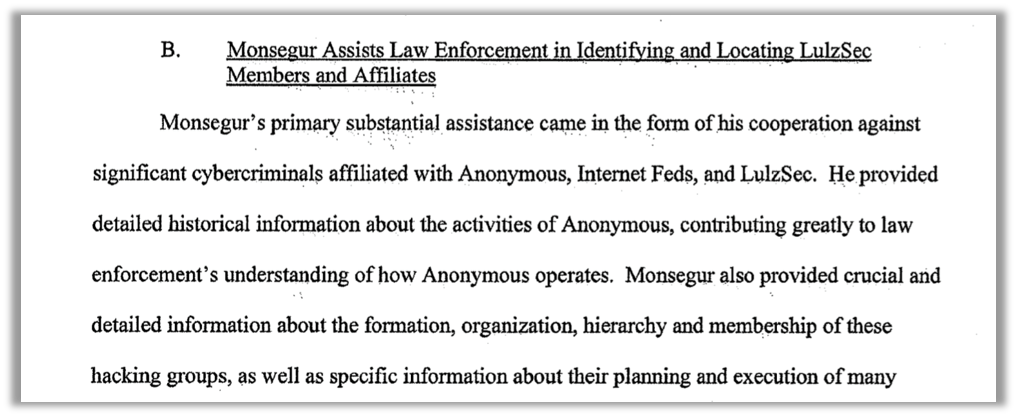

Excerpt from Monsegur’s sentencing guidelines5

As part of Monsegur’s plea deal, the authorities were given access to his Twitter account and used it to collect information about Anonymous and LulzSec sympathizers. Presumably, the identities of Sabu sympathizers now exist in some government database of ne’er-do-wells and miscreants.

It was during this time—when the FBI was managing Monsegur’s Twitter account—that the Las Vegas Rio hotel pool incident (/content/f5-labs/en/labs/articles/threat-intelligence/profile-of-a-hacker-the-real-sabu-part-1-of-2-26146.html) occurred, which I was ever so slightly involved in. That event indicated The Jester didn’t know that his nemesis had already been turned, or that the whole thing was just for show. Maybe The Jester wasn’t at the pool, either!

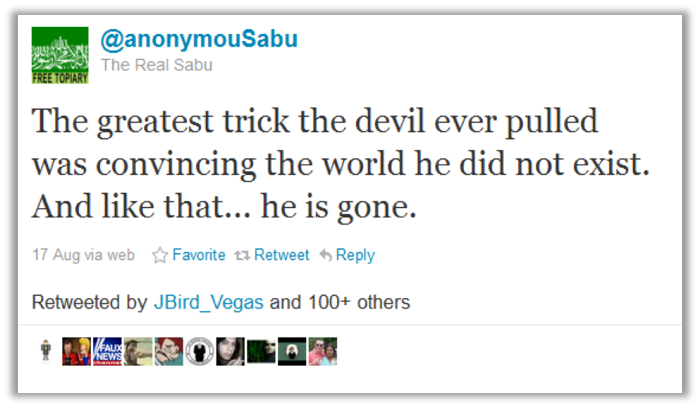

A few days later, the @anonymouSabu Twitter account appeared to cease publication with this dramatic tweet:

For the next six months, Monsegur cooperated with law enforcement authorities, providing intel on ongoing operations, stopping hundreds of cyber attacks, including three national security targets. Law enforcement also got zero-day research and exploits, and Monsegur detailed his attack methodology and strategies. The judge in Monsegur’s case praised him for his “extraordinary cooperation” with the FBI.6

Within the year, authorities had apprehended the members of LulzSec. Many are now serving long jail sentences and owe hundreds of thousands of dollars in restitution to the organizations they once brazenly penetrated. Some in Anonymous felt that Monsegur had betrayed his compatriots in LulzSec, though he denies pointing the finger. He has had little comment about it since. Monsegur himself was freed on May 27, 2014 after time served.

The younger Sabu railed against cyber security federal contractors, who he perceived as little more than highly paid snake oil salesmen. The older (and perhaps, wiser) Sabu has become a white hat, doing penetration testing work for a small Seattle-based cyber security firm. He now lives in New York City, where he, on occasion, gives interviews. He no longer Tweets as Sabu, but instead as Hector X. Monsegur.7

With LulzSec members behind bars, and Monsegur neutralized, The Jester went back to attacking Jihadist websites and gathering intel on ISIS. He blogs8 vociferously against the Trump Administration and maintains a store of “JesterGear”9 when he’s not running his own Minecraft server.