TLDR

As a follow up to the 2021 Application Protection Report, we analyzed and visualized attack chains for more than 700 data breaches to look for relationships between sectors or industries and the tactics and techniques attackers use against them. While there are some attack patterns that correspond to sectors, such as the prevalence of web exploits against ecommerce targets, the relationships appear indirect and partial, and counterexamples abound. The conclusion is that sectors can be useful for predicting an attack vector, but only in the absence of more precise information such as vulnerabilities or published exploits.

Introduction

In both the 2021 Application Protection Report (APR) and the 2021 Credential Stuffing Report, we noted that industry sectors, or verticals, appear to have limited value in terms of predicting the precise vector attackers will use against a given target. This is because the types of data and vulnerabilities in the target environment, which determine an attacker’s approach, no longer tightly correlate with the nature of the business. Despite this, however, sector-based studies of information risk are common in security intelligence, and we frequently get requests to break down threats to a specific vertical.

With this in mind, we reexamined the 2020 U.S. data breaches that formed the foundation of the 2021 APR from the standpoint of sectors. The goal is both to look for clusters of sectors and attack vectors and to see if we can determine a more precise formulation for the relationship between lines of business and attacker approaches.

U.S. Breach Causes by Sector—Simple Model

We’ll start where we left off in the APR, with a sector breakdown of breaches based on the simplified, single-stage model we used in previous reports. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the 729 data breaches we examined by sector. The most notable thing about this view is that attackers focused on the retail sector less than in 2018 and 2019. The growth of breaches in the Professional, Scientific, and Technical services; Health Care and Social Assistance; Educational Services; and Finance and Insurance sectors reflects the growth of ransomware as a reliable way to extract value from stolen data that is not easy to sell within the attacker community.

Figure 2 shows how attacker techniques vary by sector. The clear targeting pattern that was present in 2019 was not seen in 2020; in 2019, web exploits constituted 87% of retail breaches, and nearly every other sector was characterized by access breaches and email compromise. However, the Retail sector still had a larger number of web exploits than any other sector, and it was the only sector in which web exploits were responsible for more than half of the known breaches. The Other Services sector was, for the purposes of our study, dominated by professional advocacy organizations, both white collar and blue collar, and the prevalence of web exploits against these organizations was made up largely of formjacking attacks against the membership renewal service on their web applications. The surprisingly large number of web exploits against the Educational Services sector was caused by a focused campaign against an e-learning platform that was hosting data for many secondary schools in the state of California.

If the vulnerability in that e-learning application hadn’t existed, the campaign of web exploits against secondary schools would not have happened, and instead the Educational Services sector would have been characterized by third-party data loss events, nearly all of which came from the Blackbaud cloud storage breach described in the APR. In this event, the Educational Services sector would have looked very similar to the Health Care and Social Assistance or Public Administration sectors, in that the breaches were (at least viewed through this model) all either ransomware or access breaches. Hold on to this anomalous finding—this is an important clue about what sectors can and can’t tell us, which we will return to in the Conclusion.

So far, it looks like some kind of pattern, but as noted, ransomware is even more difficult to characterize as a single event than most cyberattacks, so we also broke down our attack chain analysis by sector to get a sense of each sector’s characteristics. Note that we only explore those sectors that had a significant number of events.

Attack Chain Analysis by Sector

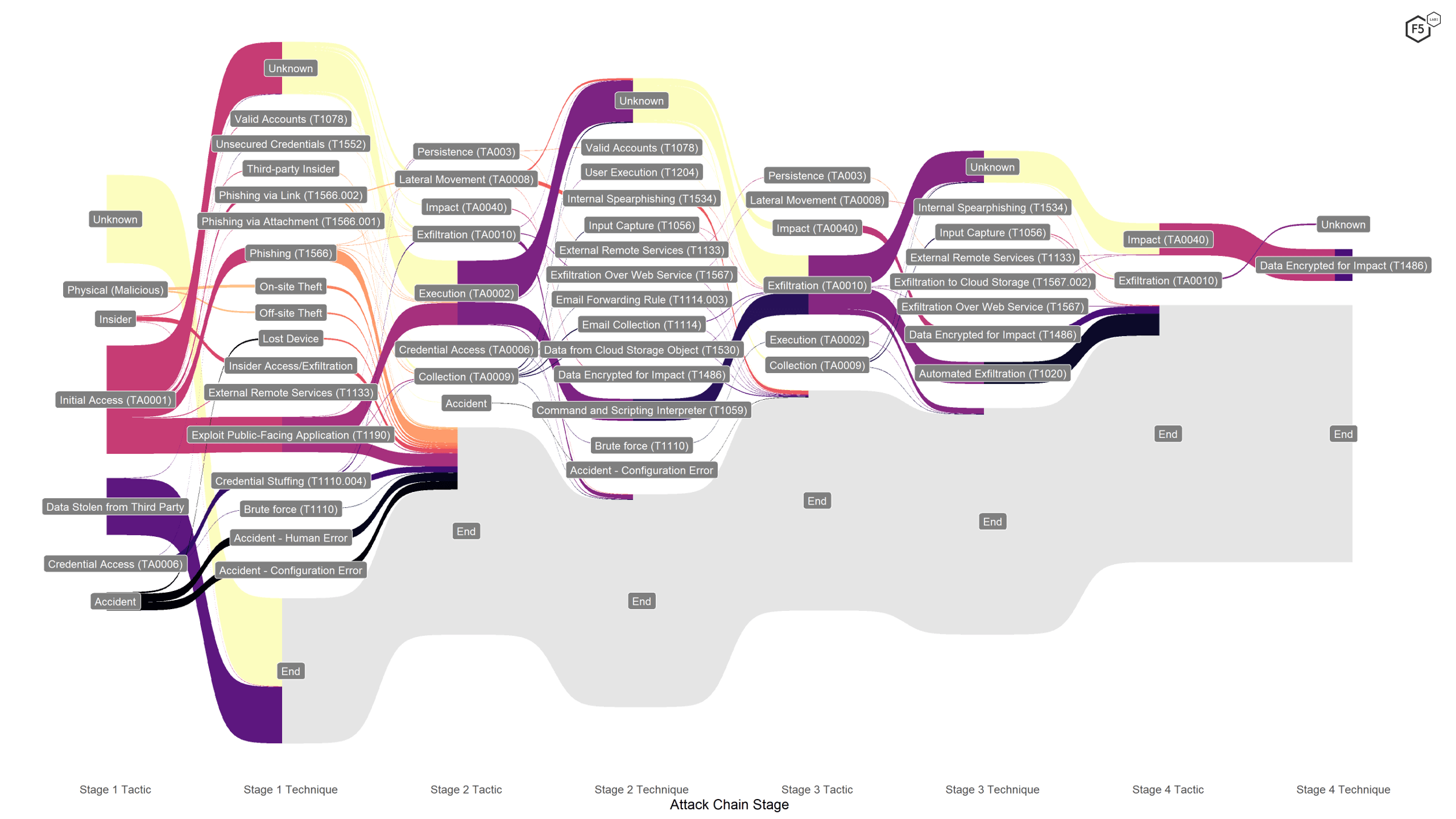

In the APR, we took pains to distinguish between tactics and techniques as laid out in the MITRE ATT&CK framework. The two most prevalent attack chains, formjacking and ransomware attacks, are dramatically different in the details but share many of the same tactical objectives, namely Initial Access, Execution, and Exfiltration. This is why the overall attack chain visualization, as shown in Figure 3, features two conspicuous threads that converge at the tactics level but diverge at the level of technique.

Figure 3. Attack chain visualization for all sectors. The two primary attack vectors, formjacking and ransomware, implement the same tactics, even if the techniques are different.

A tactics-level analysis by sector does not reveal much else of significance. These three tactics are the most frequent for nearly all sectors. The exceptions are the Impact tactic for those sectors hard hit by ransomware attacks, and the prevalence of third-party data loss in those sectors containing a large number of Blackbaud customers: Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation; Educational Services; Finance and Insurance; Health Care and Social Assistance; and to a lesser degree, Other Services.

One minor but potentially significant finding was that every occurrence of Persistence tactics occurred at organizations in the Information sector. However, only a handful of these tactics appeared in the entire data set, and the Information sector contains tech companies, telecommunications companies, and publishing companies, making it hard to determine if persistence is tied to a single kind of organization.

Attack Techniques by Sector

At the level of techniques, however, we can note some distinctions that have actionable value for organizations. We treat each sector in turn, showing the attack chains for those sectors and highlighting significant findings. This is also a good time to reiterate that many of the attack chains, particularly the ransomware breaches, left us with a decent understanding of tactics but completely in the dark about techniques.

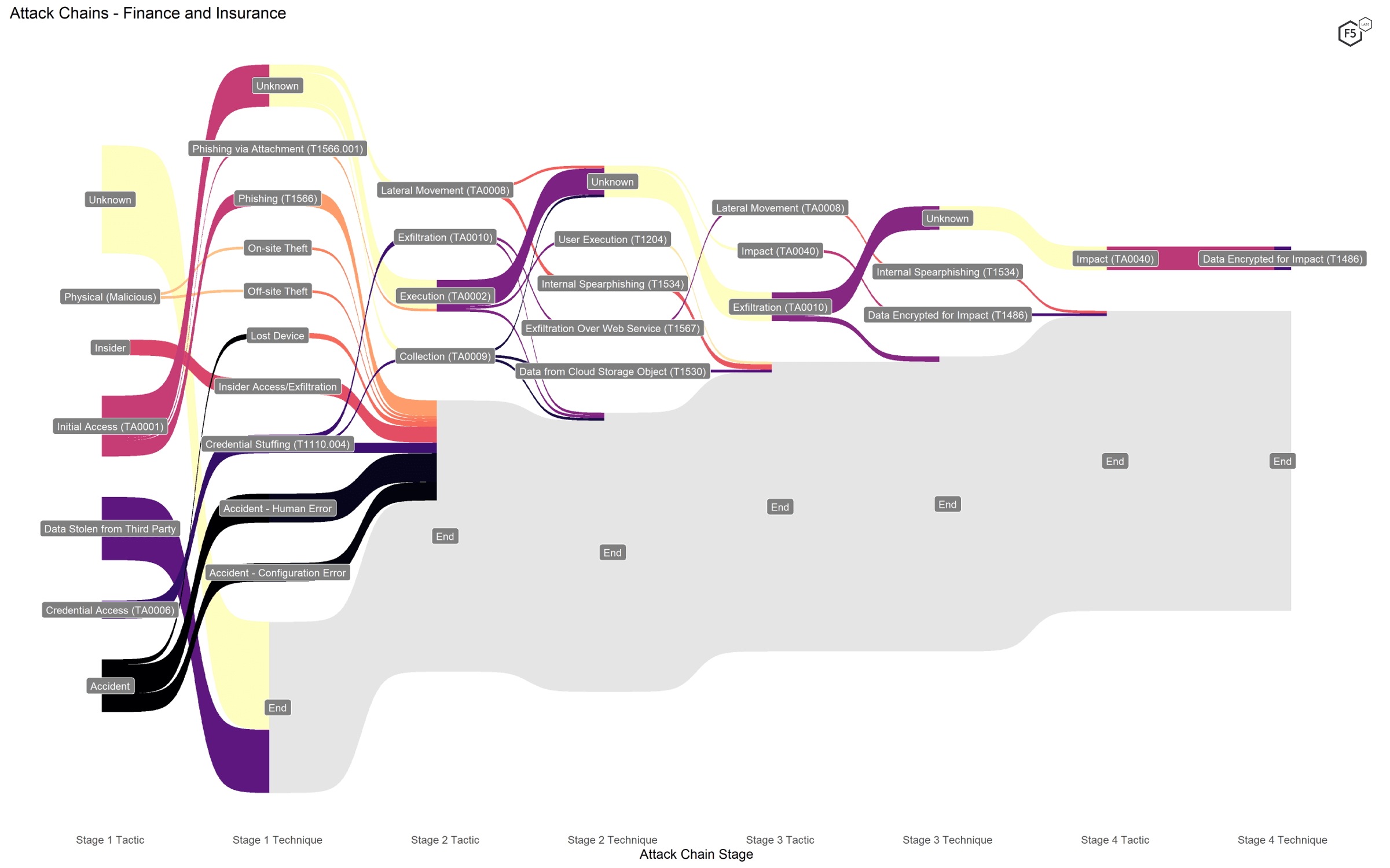

Finance and Insurance

The Finance and Insurance sector experienced a comparatively wide group of attacker techniques, particularly if we include those attacks that are not web application-specific, such as insider threats, accidents, and losses of physical devices. Figure 4 shows the attack chains against the Finance and Insurance sector.

Figure 4. Attack chains against finance and insurance companies.

While finance and insurance organizations saw many of the most common techniques, including ransomware (Data Encrypted for Impact [T1486]) and a relatively high rate of both phishing and credential stuffing, they also had a significantly higher number of accidents, both from human errors and technological misconfiguration. The finance industry also had the highest rates of insider attacks and physical data breaches.

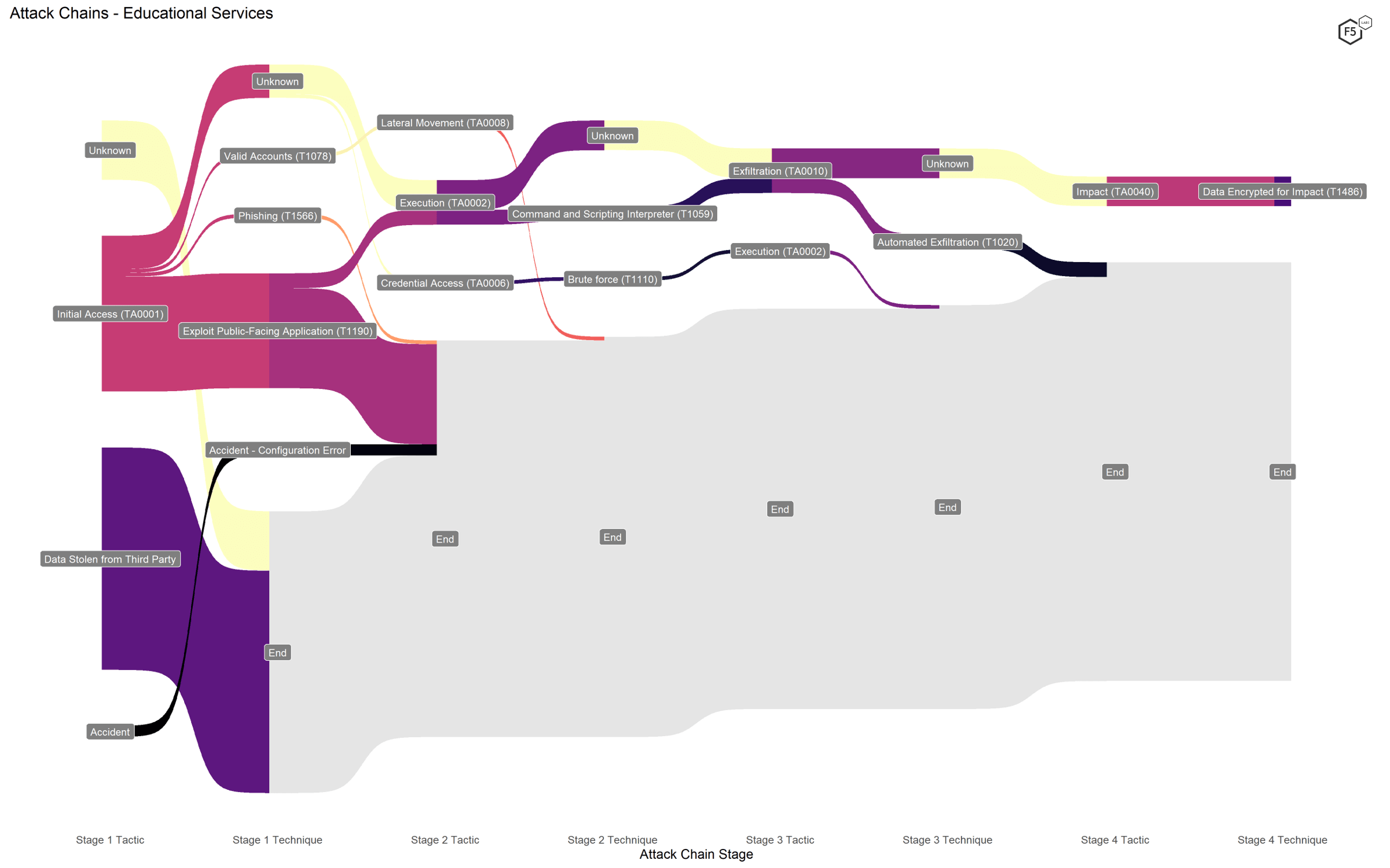

Educational Services

The ATT&CK framework validates the observation we made using the simpler model: breaches in the Educational Services sector were primarily characterized by either ransomware attack chains (including the large number of third-party losses due to Blackbaud) or web exploits, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Attack chains against educational services organizations.

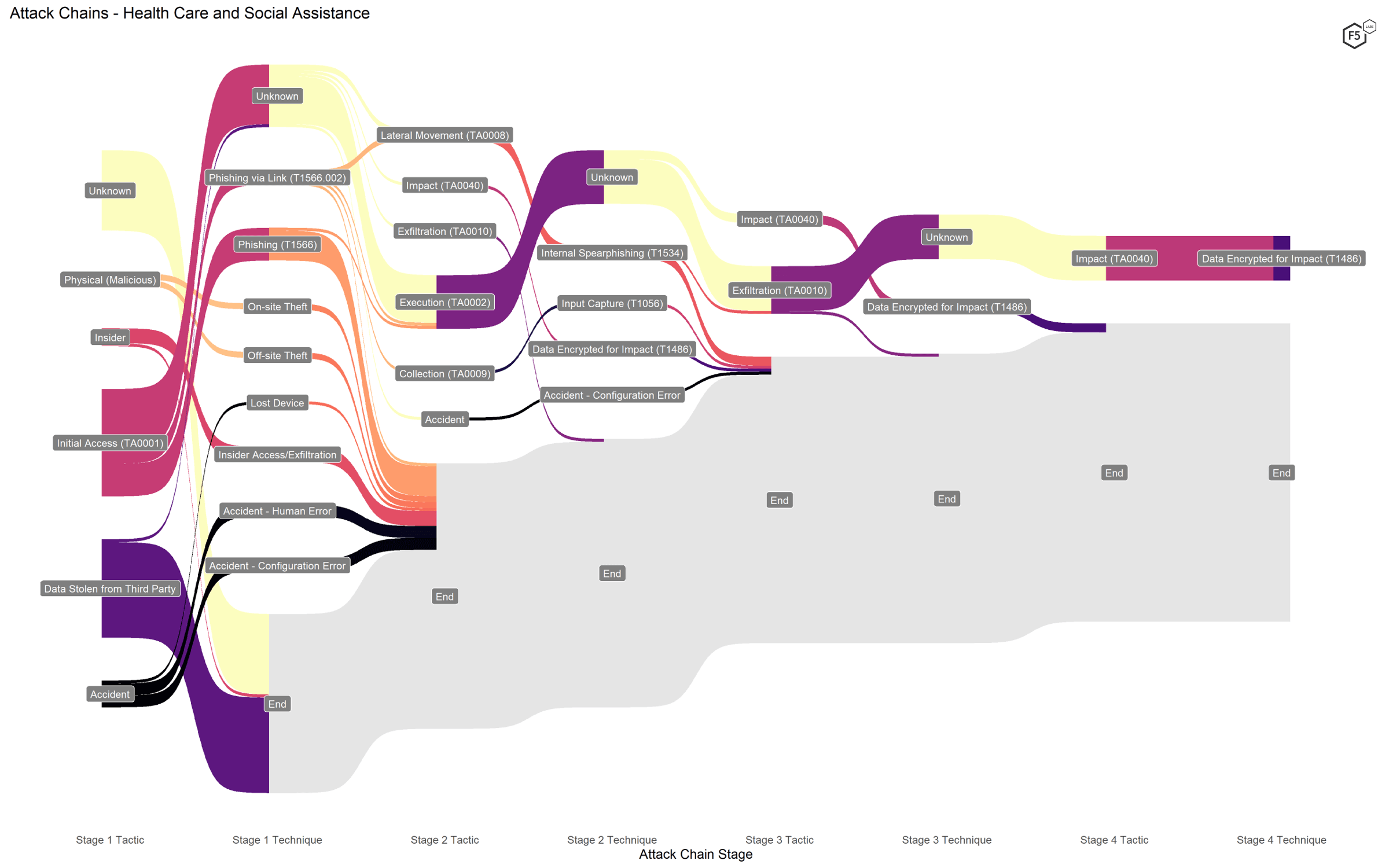

Health Care and Social Assistance

While ransomware techniques dominated the health care breaches (both regular and third-party), we also noted a significant number of phishing attacks, including some that we know used links to malicious domains, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Attack chains against health care and social assistance organizations.

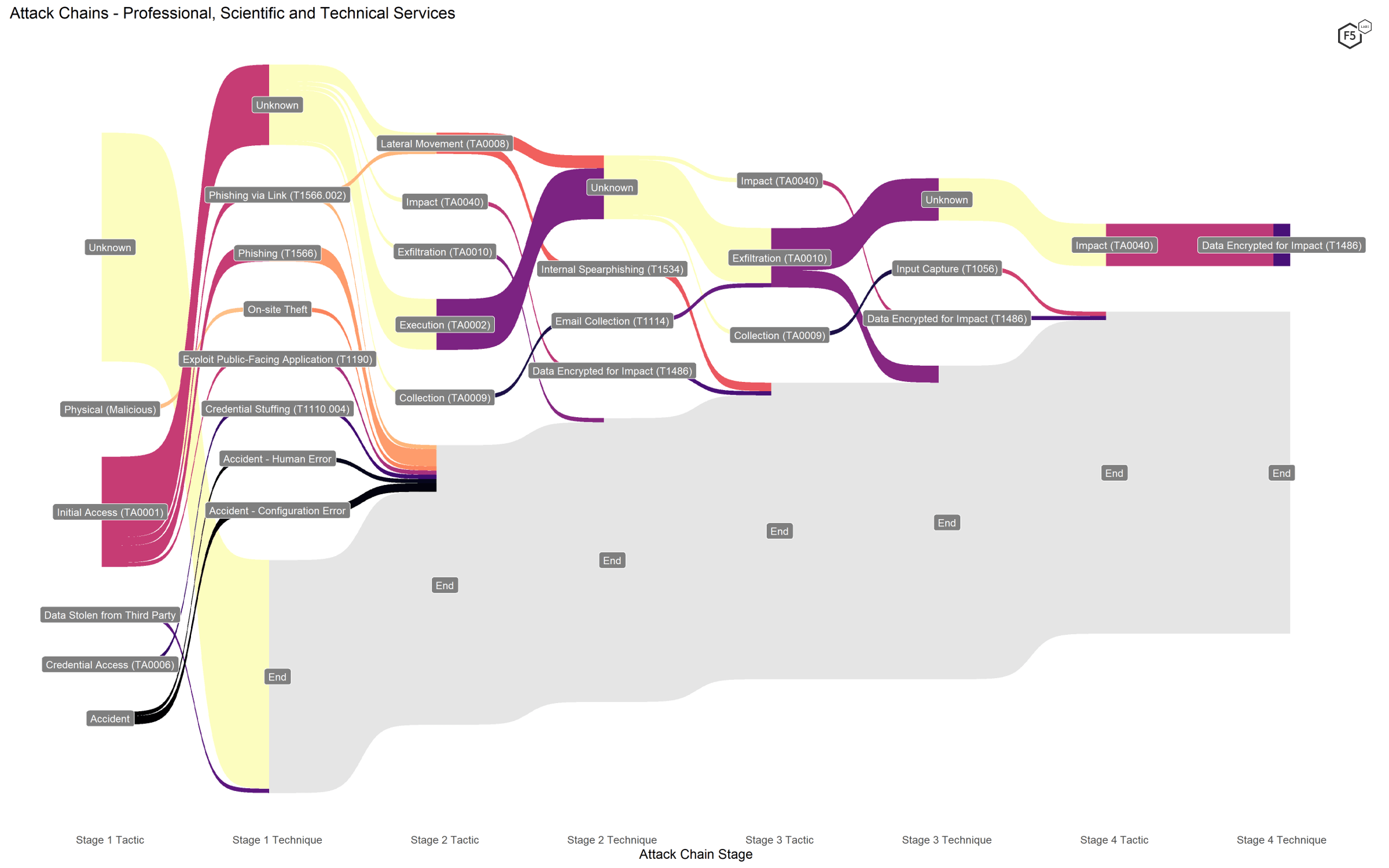

Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services

This is not a very intuitive sector designation. It includes some specialist services in information technology, such as consulting services, and specific services related to heavy industry, but it also includes both law practices and accountants. In other words, this sector captures a wide range of organizations with a presumably wide range of technical environments, data types, and security expertise. Despite these unintuitive sector boundaries, however, no techniques stood out as disproportionately common compared to other sectors, and the primary techniques were those associated with ransomware attacks, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Attack chains against professional, scientific, and technical services.

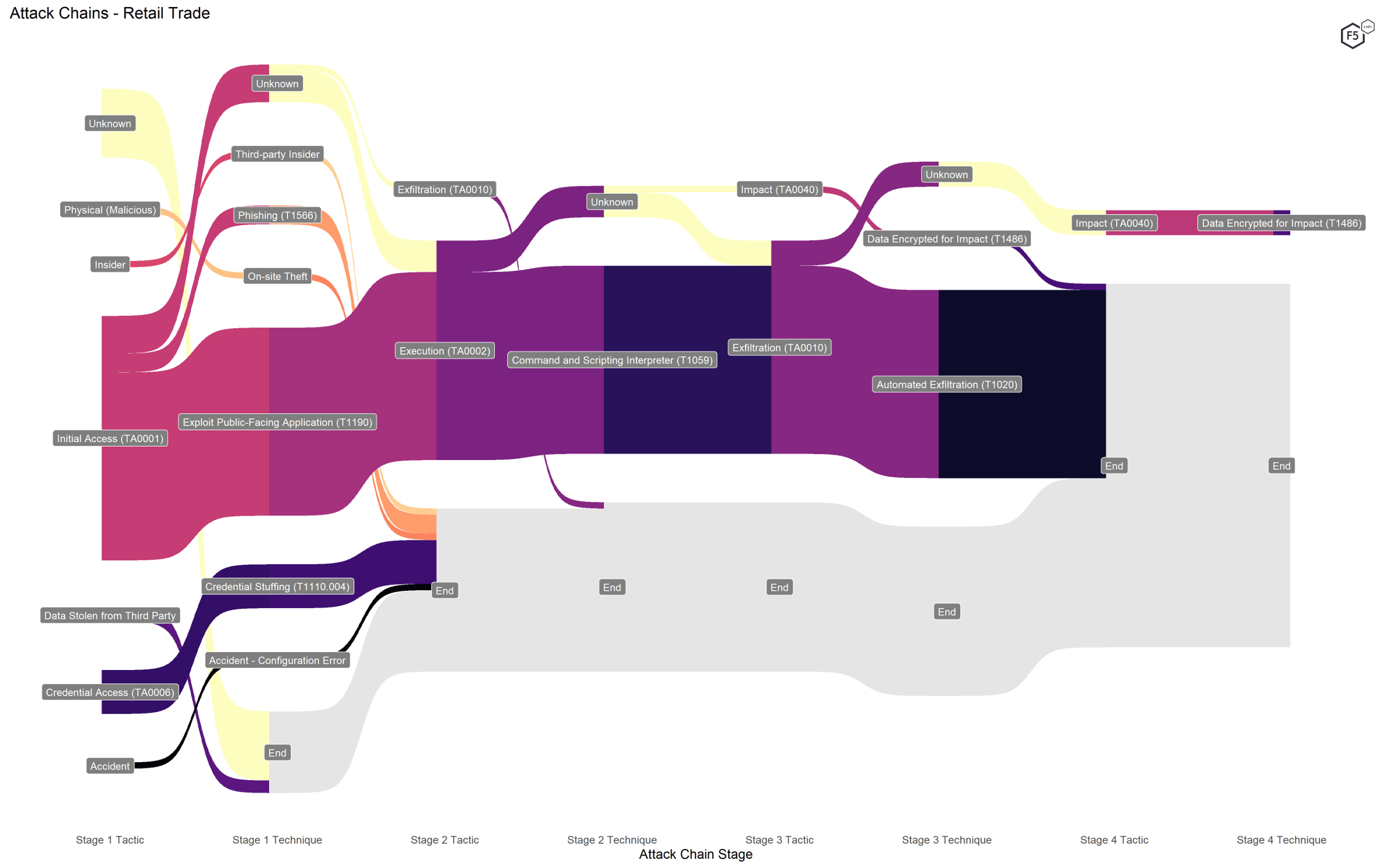

Retail Trade

Attack chains against retail organizations did not contain any surprises. We expected formjacking attack techniques, such as Exploit Public-Facing Application (T1190), use of Command and Scripting Interpreter (T1059) for execution, and Automated Exfiltration (T1020), and that’s about what we got, as shown in Figure 8. A handful of events began with credential stuffing, but comparatively few. In fact, as we noted in the APR, we suspect that the risk of credential stuffing is underrepresented in this report, and that the large number of unknown Initial Access techniques probably includes unidentified credential stuffing attacks. It was a bit of a surprise to see credential stuffing reported explicitly in this sector, but we suspect this is more about variation in detection and reporting than an attack pattern.

Figure 8. Attack chains against retail organizations.

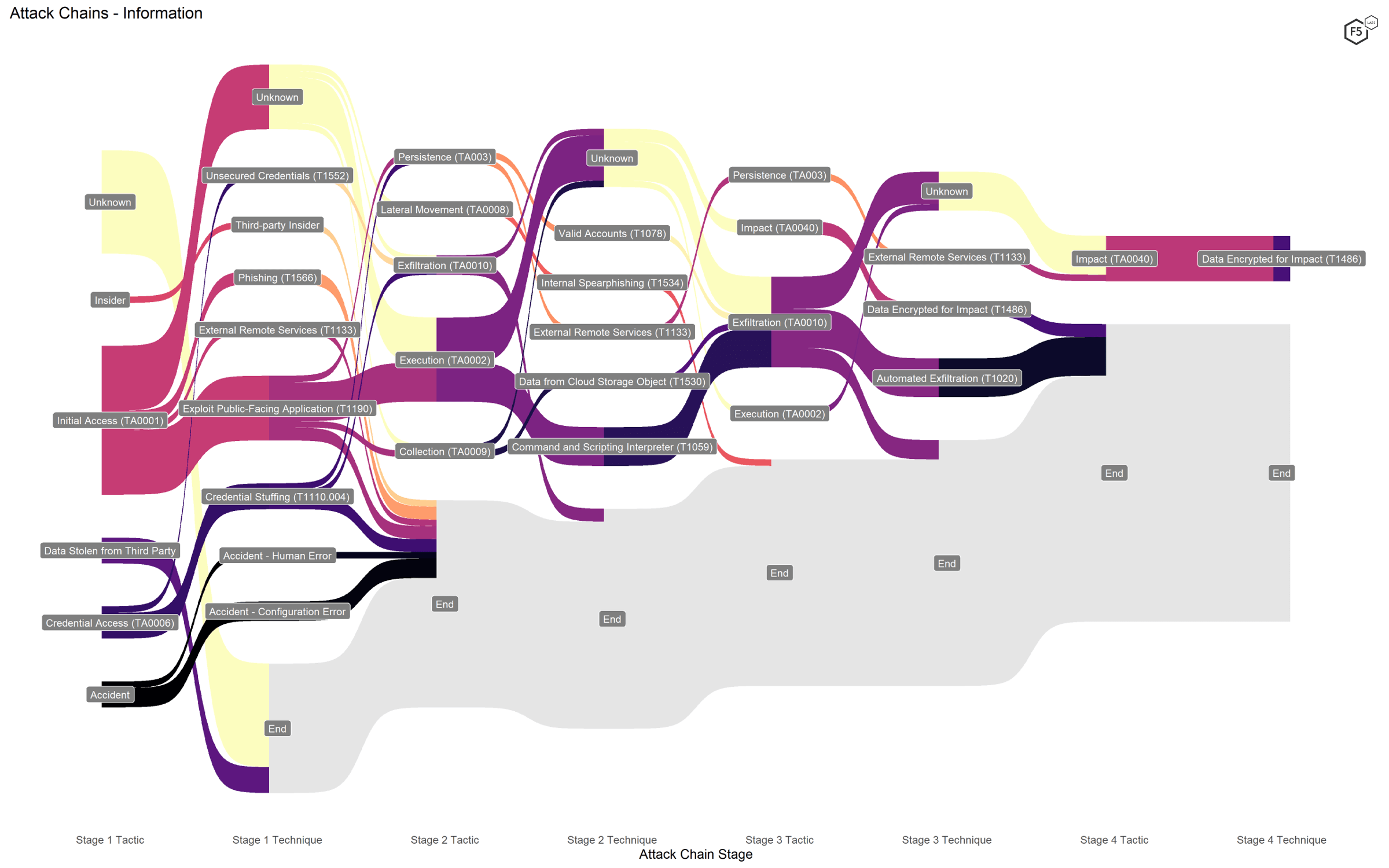

Information

The Information sector contained nearly as much variance in attack techniques as the Finance and Insurance sector (Figure 9), though we suspect this has more to do with the grab bag nature of the sector designation. This sector included a significant number of both ransomware and formjacking attacks as well as a number of non-application-focused breaches, such as accidents and insiders.

Figure 9. Attack chains against the Information sector.

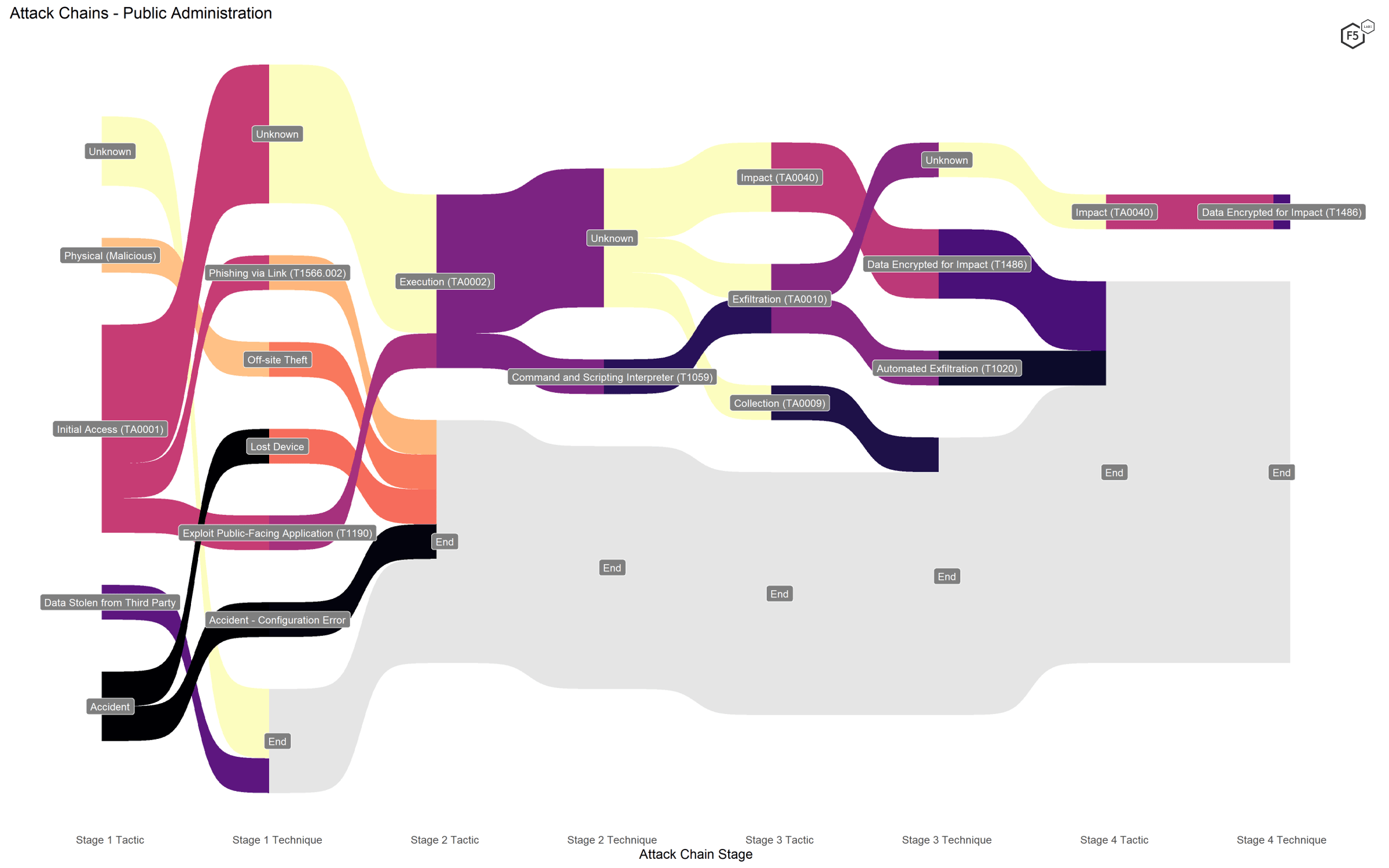

Public Administration

Breached organizations in the Public Administration sector were mostly city or town governments but also included a department of corrections and a county government. These breaches can be characterized by three findings. First, the most prevalent techniques were ransomware, although this sector was unusual in that a number of ransomware attacks did not exfiltrate information before encrypting the target’s data (Figure 10). We don’t know whether this reflects a specific aim or these attackers missed the memo on the evolution of ransomware.

The next most significant thing is the large number of non-application attacks, such as accidents and physical breaches. Finally, a small number of public administration targets were hit by formjacking attacks.

Figure 10. Attack chains against public administrations.

So How Good Are Sectors for Predicting Risk?

Based on these analyses, it appears that the answer is “not bad, but it depends.” On one hand, we can identify specific patterns that seem to map to characteristics about those sectors. We already knew that the Retail Trade sector is heavily targeted by attacks that are efficient for harvesting payment card information. The Finance and Insurance sector is notably variable in terms of breach methods but features few web exploits; human mistakes, not vulnerabilities, make up a large number of its incidents. On that level, it looks like sectors are a useful piece of information to collect about breaches.

However, the prevalence of targeted campaigns of web exploits against sectors like Educational Services and Other Services (meaning, for our purposes, professional advocacy organizations and trade unions) also shows that the moment that sector no longer correlates to more tactical target attributes like stored information type, it loses much of its predictive power. A heavy, concerted campaign of web exploits against secondary schools probably wouldn’t have been a primary concern to anyone—until a vendor shipped e-learning software with an exploitable vulnerability in it. The attackers then moved to seize an opportunity that presented itself, irrespective of what a sectoral analysis might have predicted.

This, in essence, is the clue to what sectors are good for. They give us a rough sense of what to expect in the absence of more precise targeting information. However, the moment something changes about the target—such as an extant vulnerability, the publication of a weaponized exploit, or a shift in business model that alters the type of data stored—the sector no longer serves as a good indicator.

This observation, in turn, provides us with a sense of how the kind of analyses contained in this article and in the broader APR report relate to tactical threat intelligence whose output is automated signatures and not articles. Threat intelligence, narrowly conceived, starts at the level of vulnerability and ends at the level of exploit. Broader security research starts, and often ends, at the level of sectors, and by association, compliance. This is also the level at which a lot of technological sales and strategy happens. One of the future goals for the APR series is to gather and analyze data that allows us to link these two disparate realms, in keeping with our goal to unite tactics and strategy in cybersecurity.