As organizations progress on their digital transformation journey and begin relying more on data and analytics, they will need to adjust their understanding of what an application is—and isn’t.

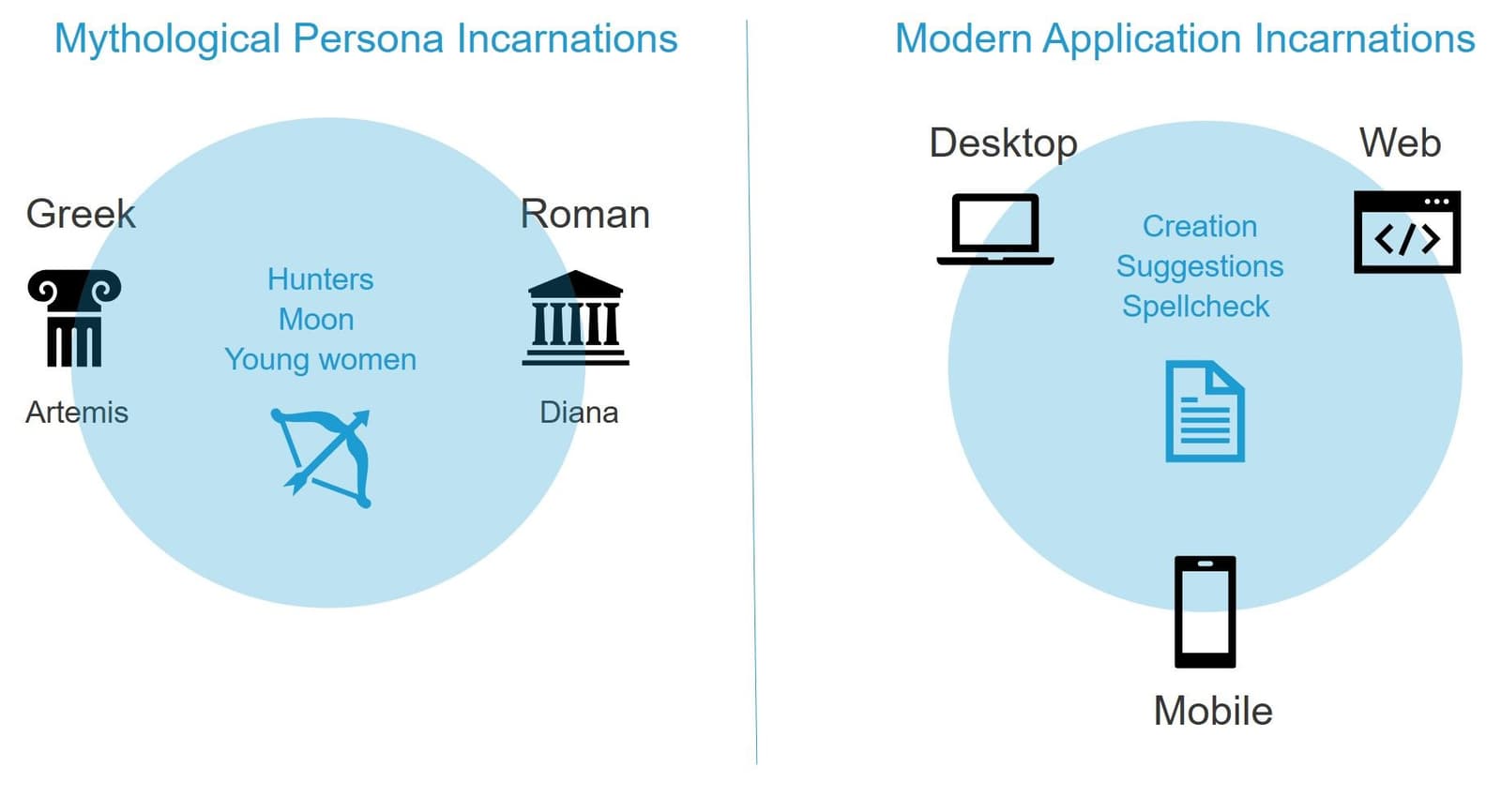

Ancient mythologies are fascinating. Well, to me they are. I’m particularly fascinated by the syncretic mythologies of the Greeks and Romans. Hellenistic—late Greek—mythology is an excellent example of how early Greek deities transformed to align with Roman counterparts. Diana the Huntress, a Roman and Hellenistic deity, is mythologically aligned with the early Greek goddess, Artemis. Her name is different, but she was functionally equivalent.

These multiple manifestations of the same persona are evident in other mythologies, as well. At the core, each incarnation is merely a new face to an existing persona.

A similar reality is true for the digital world. What we call "applications" are often incarnations of existing functionality.

Microsoft Word as an Extant Example

We have always looked at applications as a singular construct, usually tied to a business function. Microsoft Word is an application with a focus on word processing. At one time it was a monolith that progressed to a client-server application and was ultimately augmented by a web-based application.

But it is still a singular "application" in that its business function has not changed despite manifesting this function in various architectural incarnations.

Consumers don’t necessarily see it that way. It is a single application, and it must provide the same capabilities whether on the desktop, my mobile phone, or the web. It is essential that the interface be consistent across all incarnations, regardless of its architectural implementation.

Now, to go back to our mythological analogy, if I were a Greek traveler in the ancient, Hellenistic world—maybe I’m following in the footsteps of Alexander the Great—I could reasonably expect to drop in at a temple to Diana and have an experience like that of a temple to Artemis. She’s still the huntress, still responsible for the same domains, and ultimately the most substantial difference is her name.

The same is true when I shift from web to desktop to work on a document. I have a familiar experience. The application essentially works the same on all platforms.

Notice I said "the application." Because in the eyes of the consumer, it is the same application, regardless of how that application is packaged, deployed, and delivered. From a technology perspective, there are multiple applications that make up what we call Microsoft Word, but from a user experience perspective, there is only one.

So What?

As business progresses on its digital transformation journey, we will see a technology evolution accompany it. One of those evolutions will be how we define—and therefore operate and secure—applications.

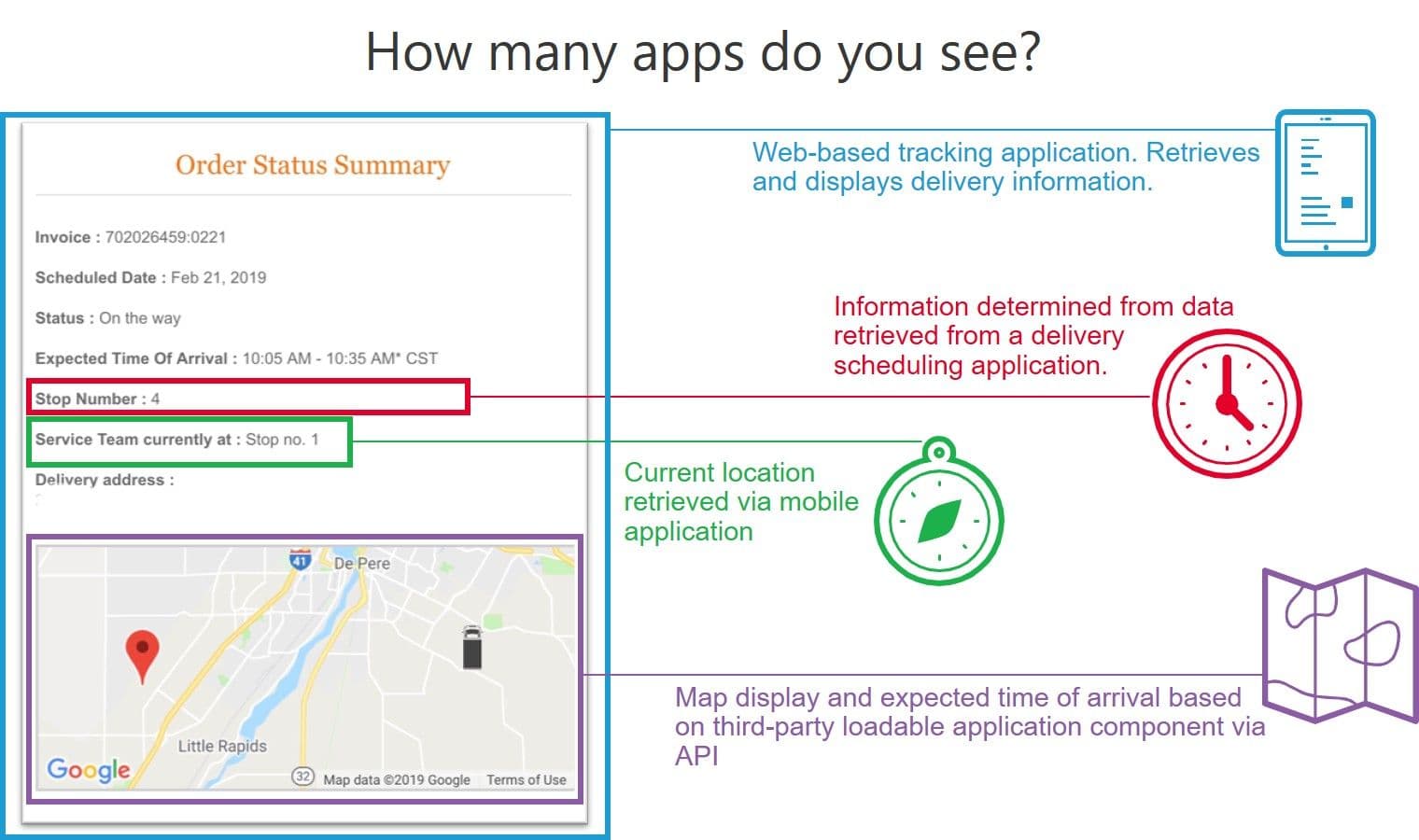

This visualization is a reminder of the digital reality we operate in: the user experience is not a single application, but rather the amalgamation of multiple applications.

The user does not care—nor should they—that the experience they have relies on myriad applications, as well as app security and delivery technologies. The user does not care—nor should they—that those apps may be a mix of custom, traditional, and modern, hosted across a variety of cloud, data center, and edge locations.

The reality for the user is the digital experience. The experience is greater than the sum of its applications and supporting technologies.

That said, we still need to be able to distinguish between the architectural constructs that make up "an application" to better align with the customer and the business—neither of which sees nor necessarily cares about the myriad working parts that must interlock and interoperate to deliver an extraordinary digital experience.

When the business says "application," it means the digital experience. It means everything that makes up that application—from back-end to delivery and security technologies to front-end interfaces. If it could possibly impact the user experience, it’s part of the application.

One of the disheartening findings from our annual research was that nearly one-quarter (24%) of organizations do not apply SLAs related to the health and performance of components that extend (modernize) traditional applications. That means that even if you’ve built a mobile app to interface with existing traditional applications—perhaps established core business functions—organizations aren’t necessarily concerned with the performance of the mobile app.

That’s a disturbing thought, given that we know mobile apps are often the first digital impression a user has of a company and that mobile users are prone to deleting apps after just one poorly performing experience.

Ultimately, we need to shift our understanding of "an application" to align with the customer perspective and recognize that an application today is really a workflow that creates an experience. That means multiple, integrated, and orchestrated workloads that each need to be monitored and measured individually in addition to being monitored and measured as a holistic construct.

Recognizing that "an application" is an experience will go a long way to improving it and ensuring a successful digital transformation journey.

About the Author

Related Blog Posts

Multicloud chaos ends at the Equinix Edge with F5 Distributed Cloud CE

Simplify multicloud security with Equinix and F5 Distributed Cloud CE. Centralize your perimeter, reduce costs, and enhance performance with edge-driven WAAP.

At the Intersection of Operational Data and Generative AI

Help your organization understand the impact of generative AI (GenAI) on its operational data practices, and learn how to better align GenAI technology adoption timelines with existing budgets, practices, and cultures.

Using AI for IT Automation Security

Learn how artificial intelligence and machine learning aid in mitigating cybersecurity threats to your IT automation processes.

Most Exciting Tech Trend in 2022: IT/OT Convergence

The line between operation and digital systems continues to blur as homes and businesses increase their reliance on connected devices, accelerating the convergence of IT and OT. While this trend of integration brings excitement, it also presents its own challenges and concerns to be considered.

Adaptive Applications are Data-Driven

There's a big difference between knowing something's wrong and knowing what to do about it. Only after monitoring the right elements can we discern the health of a user experience, deriving from the analysis of those measurements the relationships and patterns that can be inferred. Ultimately, the automation that will give rise to truly adaptive applications is based on measurements and our understanding of them.

Inserting App Services into Shifting App Architectures

Application architectures have evolved several times since the early days of computing, and it is no longer optimal to rely solely on a single, known data path to insert application services. Furthermore, because many of the emerging data paths are not as suitable for a proxy-based platform, we must look to the other potential points of insertion possible to scale and secure modern applications.