The news is full of stories about Russian hacking and speculation about their motivations. These hackers have been implicated in influencing elections as well as some of the largest cybercrime heists in history. In March of 2017, then FBI Director James Comey stated, “Russian intelligence services hacked into a number of enterprises in the United States, including the Democratic National Committee.”1

Russian hacking, however, is not a new threat. Over the years, there have been quite a few infamous Russian hackers, including:

- Roman Seleznev, convicted in 2016 of 38 counts of financial cybercrime for the hack of RBS Worldpay payment processor.4

- Evgeniy Bogachev, wanted by the FBI as the bot master of the GameOver Zeus botnet,5;used for bank fraud and ransomware.

- Sasha Panin, who hacked over a million systems, stealing credit cards and bank account credentials.6

- Vladimir Drinkman, who pleaded guilty to a hacking theft of 160 million credit card numbers.7

- Leo Kuvayev, the Spam king and Trojan master.8

- Dmitry Sklyarov, who was charged with selling copy-protection breaking software.9

Russian hackers are indeed formidable and responsible for a fair share of cybercrime and Internet mayhem. But this raises a lot of questions: Why are they so good at hacking? What is their motivation to hack? Aren’t they worried about getting caught? Are they spies or crooks or both?

I will attempt to answer these questions with the words of real Russian hackers that I interviewed face to face, as part of an FBI undercover operation that took place in 2000.

Operation Flyhook

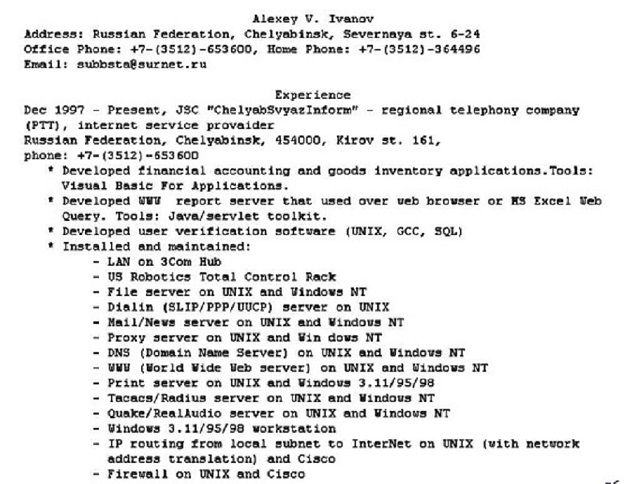

Alexey Ivanov, a.k.a. Subbsta

Alexey Ivanov, a.k.a. Subbsta

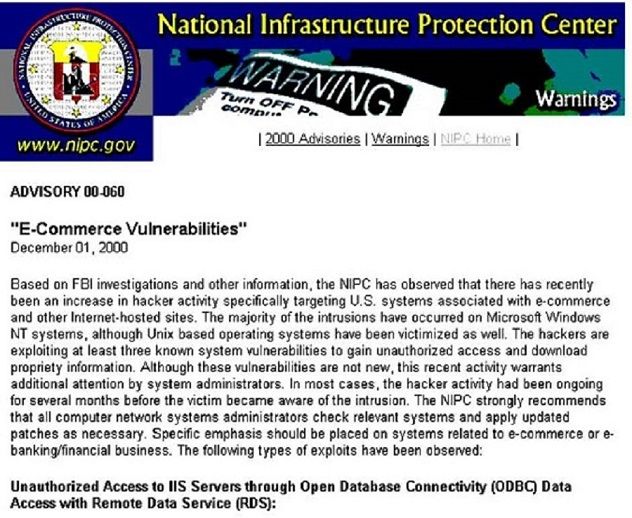

Hacking systems and launching denial-of-service attacks was nothing new, even back in 1999. However, in the latter half of that year there was a noted uptick in high-profile cyber attacks against ISPs, e-commerce companies, and banks. Systems were brought down, and data was being stolen or erased. A hacker known as “Subbsta” and his gang were becoming known for approaching breached organizations and offering “security consulting” services to minimize further damage. In other words, cyber-extortion. Pay up or face more deleted or breached data.

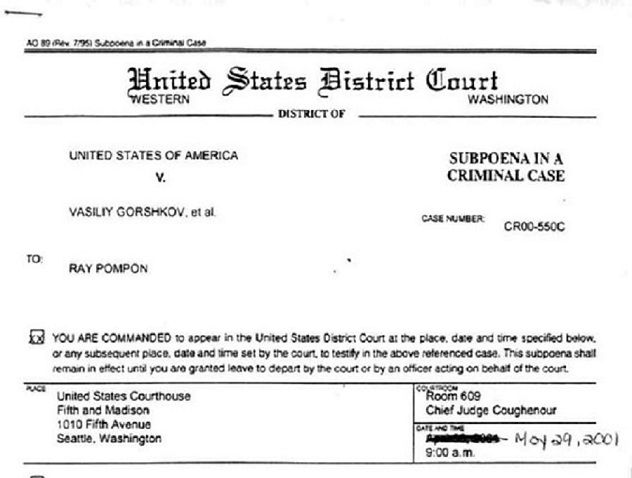

Working with a victimized Seattle ISP, the FBI cooked up Operation Flyhook, a plan to lure this hacker to the United States and apprehend him. Taking a cue from the hacker’s request for an extortion payment, the FBI upped the stakes and offered the hacker Subbsta a job at a fictitious security consultancy.

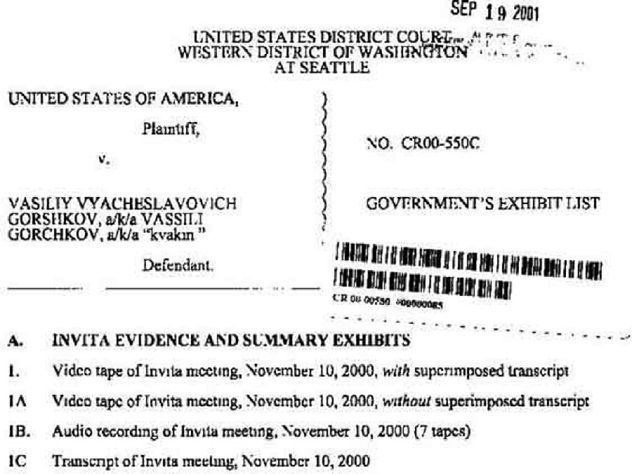

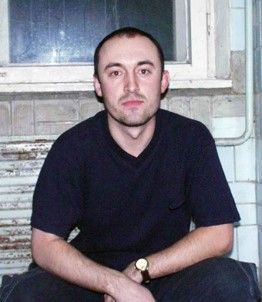

Two members of the hacking gang took the bait. Alexey Ivanov “Subbsta” and Vasiliy Gorshkov “Kvakin” of Chelyabinsk, Russia flew to Seattle and were interviewed in that sting operation.

Vasiliy Gorshkov, a.k.a. Kvakin

Vasiliy Gorshkov, a.k.a. Kvakin

Ivanov’s and Gorshkov scheme was both elaborate and impressive: credit card numbers were stolen from PayPal accounts, acquired through well-crafted phishing attacks. Then, these credit card numbers were used by bots to purchase goods in eBay auctions. Goods purchased from eBay were shipped into Russia for resale. Ivanov and Gorshkov were not just creative in these pursuits; their hacking skills were top notch, as well. The lead forensics expert on the case told me, “These are some of the best system integrators I’ve ever seen.” In fact, Ivanov and Gorshkov were responsible for discovering and exploiting several root-level zero-day exploits. The US government would later issue a few major alerts regarding these holes.

The Operation Flyhook sting consisted of three undercover FBI agents and a civilian cyber-security expert: me. At that time, the FBI did not have deep, technical cyber-security expertise on staff as they do now. I was already working with the FBI on a few other matters, so I volunteered to assist in interviewing Ivanov and Gorshkov to establish evidence of their guilt. The interview also gave me an opportunity to understand the motivations and capabilities of the people attacking the systems I defended in my day job. It was an illuminating experience.

First of all, I expected them to be evil men; to my surprise, they were not. They were techies like me. They loved technology and enjoyed devising interesting and powerful new ways to use it. Second of all, Ivanov and Gorshkov were challenged in making use of their skills in their native country. There were no technology companies to join, and startups were impossible to fund. There weren’t very many IT jobs at all, since Russia had not adopted that kind of technology at that time.

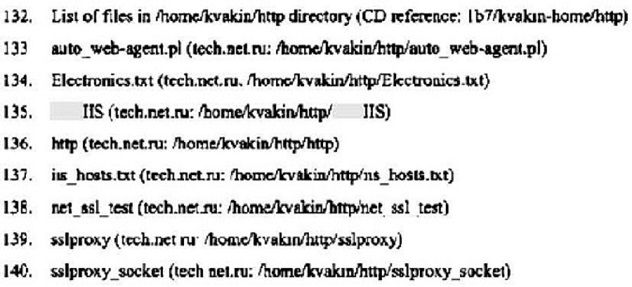

With the limited resources of Russia—then only a decade out from the fall of the Soviet Union—talented and ambitious technologists had to teach themselves and stretch every resource they had. Gorshkov told me, “We build computers ourselves because it is much cheaper and much faster.” Those who succeeded were often highly creative and innovative and also possessed a deep understanding of technology, as is evident from my interview with them, Ivanov’s resume, and the array of hacking tools discovered during the forensic investigation.

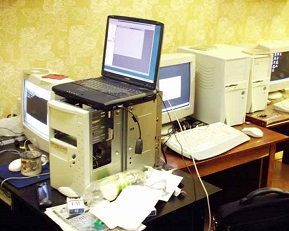

These hackers lived where the bending and breaking of the rules was just a part of the culture. Both men were astonished at how Americans obeyed traffic rules and smoking restrictions, citing how in their country such rules are ignored. They wanted to go into business for themselves but found it difficult to do so. During the interview, Gorshkov said of his home town of Chelyabinsk, “Here, it is difficult for a person to live on honest wages.” They spent a portion of our interview talking to us about their startup business, Tech.Net.Ru. They even shared a photo of their office and equipment.

At the time, the first dot-com boom was exploding in Silicon Valley and Seattle. They wanted to be part of it, not just because of the money, but also to apply their skills and build something innovative. The underlying purpose for the hacking and extortion scheme was to raise funds until they could get their e-commerce platform off the ground. They talked about themselves as businessmen and entrepreneurs.

When asked about law enforcement response, Gorshkov joked that, “The FBI cannot get us in Russia,” which is why they only committed their crimes while in Russia.

They did express concern about being caught and “recruited” while in Russia. At first, we thought they might be referring to being recruited by traditional organized crime gangs. However, they were referring to “agencies” in Russia who would use their talents for their own ends. These agencies including the aforementioned FSB, which was involved in the recent Yahoo hack, or the Russian military intelligence (GRU). These agencies would not bother with due process or evidence when they found a hacker; rather, "they would take you" and then "you would work for them." Ivanov and Gorshkov were talking about forced recruitment and the end of their freedom. This is a telling hint about why Russian cyber-criminals are not extradited and what becomes of them if caught. They end up working for agencies on state-sponsored hacking missions.

Conclusion

After the interviews, Ivanov and Gorshkov were taken offsite, arrested, and eventually convicted of their crimes.10 There were more twists and turns in Operation Flyhook. If you’re interested in more details, I recommend checking out The Lure: The True Story of How the Department of Justice Brought Down Two of The World's Most Dangerous Cyber Criminals11by Steve Schroeder, one of the prosecutors in the case. You’ll find Ivanov, Gorshkov, and me right there in Chapter Four.

Looking at Russian hackers in a threat profile, you can see there are really two primary branches: criminals and state hackers, with the criminals being press-ganged into doing work for Russian agencies. Things really haven't changed; Dmitry Dokuchaev, mentioned earlier associated with the Yahoo hack, was reportedly recruited into the FSB to avoid prosecution for fraud.12 Russian cybercriminals act as you would expect: earning a good living while trying to remain below the radar from Russian agencies and foreign law enforcement. They are often extremely technologically adept and often unreachable by law enforcement. Russian hackers are also very skilled at social engineering, usually employing well-designed phishing schemes and social media decoys. They are true hackers in the original sense of the word: they will chip away at a system for as long as it takes to find a way in. And often they will succeed.